memorial sloan kettering cancer center

Evolution reveals missing link between DNA and protein shape

Fifty years after the pioneering discovery that a protein’s three-dimensional structure is determined solely by the sequence of its amino acids, an international team of researchers has taken a major step toward fulfilling the tantaliz…

New way of expanding cancer screening for minority women

FOR EMBARGOED RELEASE:

October 25, 2010 12:01AM ET

New Way of Expanding Cancer Screening for Minority Women

New York, October 25, 2010 — Minority patients have a significantly decreased survival from colon ca…

DNA-based vaccine triples survival for dogs with melanoma

The options for treating advanced melanoma are limited – regardless of whether the patient is a dog or a human. Because this deadly cancer is virtually resistant to chemotherapy and radiation in its late stages, new approaches are being investigated including vaccines that harness the immune system. For nine dogs that naturally developed canine malignant melanoma, treatment with a new DNA-based vaccine more than tripled their median survival from an expected 90 days to an average of 389 days.

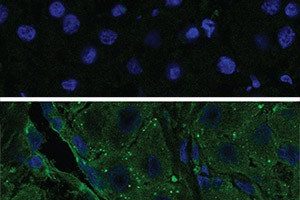

Targeted immunotherapy eradicates cancer in mice

Researchers have developed a novel approach to genetically instruct human immune cells to recognize and kill cancer cells in a mouse model. The investigators plan to ultimately apply this strategy in a clinical trial setting for patients with certain forms of leukemias and lymphomas. Scientists at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) genetically engineered an antigen receptor, introduced it into cultured human T cells, and infused the T cells in mice that bear widespread tumor cells. The modified T cells, now able to recognize the targeted antigen present on the tumor cells, eradicated the cancer.

Mutation in DKC1 Gene Can Cause Rare Aging Disease and Cancer

A rare genetic syndrome, Dyskeratosis Congenita (DC), may hold the key to understanding a mechanism that causes premature aging and cancer. Recreating DC in genetically altered knockout mice, researchers at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and colleagues proved that the disorder was caused, as theorized, by mutations in the DKC1 gene. Unexpectedly, they also showed that DC was caused by a disruption in ribosome function and not due to shortened telomeres (the distal end of a chromosome arm) as previously hypothesized. Their results, published in the January 10 issue of Science, may have implications for development of drugs that kill cancer cells by specifically targeting ribosomes, similar to the way ribosome targets have been key to the development of antibiotics for specific bacterial infections.

Study helps explain gene silencing in developing embryo

In an embryo, certain genes must turn on to, for example, tell cells to develop into a limb. But just as importantly, the genes must then turn off, or go silent, to prevent abrnomral growth. How the genes do that gets some new light in research released out of North Carolina.