Creating induced pluripotent stem cells or iPS cells allows researchers to establish “disease in a dish” models of conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s disease to diabetes. Scientists at Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University have now applied the technology to a model of Huntington’s disease (HD) in transgenic nonhuman primates, allowing them to conveniently assess the efficacy of potential therapies on neuronal cells in the laboratory.

The results were published this week in Stem Cell Reports.

“A highlight of our model is that our progenitor cells and neurons developed cellular features of HD such as intranuclear inclusions of mutant Huntingtin protein, which most of the currently available cell models do not present,” says senior author Anthony Chan, PhD, DVM, associate professor of human genetics at Emory University School of Medicine and Yerkes National Primate Research Center. “We could use these features as a readout for therapy using drugs or a genetic manipulation.”

Chan and his colleagues were the first in the world to establish a transgenic nonhuman primate model of HD. HD is an inherited neurodegenerative disorder that leads to the appearance of uncontrolled movements and cognitive impairments, usually in adulthood. It is caused by a mutation that introduces an expanded region where one amino acid (glutamine) is repeated dozens of times in the huntingtin protein.

The non-human primate model has extra copies of the huntingtin gene that contains the expanded glutamine repeats. In the non-human primate model, motor and cognitive deficits appear more quickly than in most cases of Huntington’s disease in humans, becoming noticeable within the first two years of the monkeys’ development.

First author Richard Carter, PhD, a graduate of Emory’s Genetics and Molecular Biology doctoral program, and his colleagues created iPS cells from the transgenic monkeys by reprogramming cells derived from the skin or dental pulp. This technique uses retroviruses to introduce reprogramming factors into somatic cells and induces a fraction of them to become pluripotent stem cells. Pluripotent stem cells are able to differentiate into any type of cell in the body, under the right conditions.

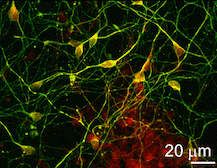

Carter and colleagues induced the iPS cells to become neural progenitor cells and then differentiated neurons. The iPS-derived neural cells developed intracellular and intranuclear aggregates of the mutant huntingtin protein, a classic sign of Huntington’s pathology, as well as an increased sensitivity to oxidative stress.

The sensitivity to oxidative stress was a useful indicator; it could be ameliorated in cell culture, either by a RNA-based gene knockdown approach, or the drug memantine, which is currently being investigated for Huntington’s disease in a human clinical trial.

“We tested two known experimental interventions, but our findings are a proof of principle that this system could be a valuable tool for the discovery and evaluation of other therapies,” Chan says.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (5R24OD010930 and primate centers: P51OD11132 – formerly NCRR P51RR000165).