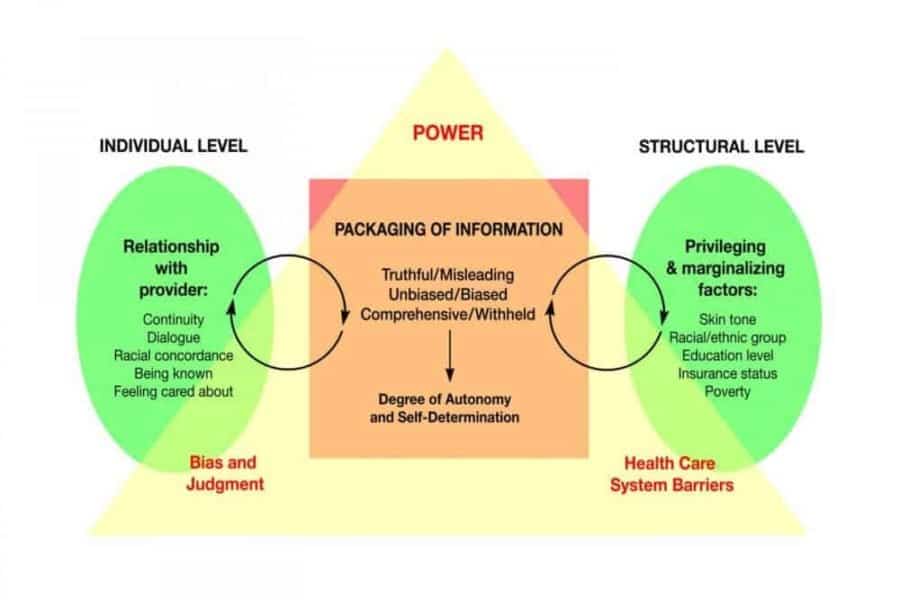

A new study finds that women of color perceive their interactions with doctors, nurses and midwives as being misleading, with information being “packaged” in such a way as to disempower them by limiting maternity healthcare choices for themselves and their children.

“Given the significant birth-related disparities faced by women of color, particularly black women, this study illuminates a previously undescribed aspect of the patient-provider interaction,” said University of Washington assistant professor Molly Altman, lead author of the study published online in the journal Social Science & Medicine.

“How providers shared or didn’t share appropriate information about options, risks and possible outcomes was perceived as biased and dependent on whether providers saw them as individuals capable of making good decisions,” said Altman. Now at the UW School of Nursing, Altman conducted the research while a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California San Francisco as part of its California Preterm Birth Initiative.

The study participants said that while they wanted complete, truthful and comprehensive information about their care and options available, they felt information was “packaged” in a way that reflected what the provider thought the patient should do, based on bias, and was “disrespectful.”

One participant said she felt like her providers were “harassing” and “bullying” her to get tests she didn’t want. Another said she wanted to “do a little bit more research” into vaccinations before getting them for her children, and said her provider “was like, ‘Well, I thought that you cared about your children. But if that’s not the case, then feel free to go.'”

Researchers interviewed 22 self-identified women of color from the San Francisco Bay Area who had given birth within the previous year. The interviews were open-ended discussions of the participants’ experiences in pregnancy, birth and postpartum care and took place between September 2015 and December 2017. The researchers point out in their paper that they used a method of analysis that “acknowledges the subjective and involved nature of the researcher in relation to the participant” to account for the interpersonal nature of the research.

“The results of our study were not surprising in the sense that communities of color have long known that providers often use their power to influence health-related communication and decision-making,” Altman said. However, she added, “given existing evidence of the impacts of implicit bias and racism on birth outcomes, this study provides a potential mechanism for how this association occurs.”

The authors explain that while providers have to consider health literacy of patients and tailor information to make it understandable, there is a difference between providing information in understandable language and packaging information based on prejudice and assumptions, or not providing information at all.

One participant said that during a postpartum hemorrhage, she received no information about what was happening to her and was treated as if she were not part of the situation.

“It was scary because I didn’t know what was happening, and, I mean, it was obvious that it was a serious issue because of, like, the look on everyone’s face and, like, how — how no one was even talking to me,” the participant said.

Another participant explained that when she told her health care providers she was a student at the University of California, Berkeley, they treated her differently.

“They’re like, ‘Oh, maybe she’s not a crazy black woman,’ or something, you know? … It just makes me feel weird because, one, I feel like I’m accessing on like a certain type of privilege. And I feel like a part of me does it on purpose because I know that they’re going to treat me better after I say that,” the participant said.

The researchers hope the study provides evidence that will lead to improved provider training in power differentials, informed consent and providing respectful care.

“Our study is one of the first to evaluate how information and power are exchanged between providers and patients from the perspective of the people we serve,” said Monica McLemore, the study’s co-author and an associate professor at the UCSF School of Nursing. “I believe these data are critical in developing new models of partnership, specific to how black women and other people with the capacity for pregnancy want and need to receive information that is essential for their care and decision-making.”

Co-authors are Talita Oseguera and Linda Franck at UCSF; Ira Kantrowitz-Gordon, at the UW; and Audrey Lyndon at New York University. This research was funded at the University of California, San Francisco, by Marc and Lynne Benioff and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.