From the black plague to the Spanish flu, Ebola and now Covid-19, our societies have weathered a number of severe health crises, as historian Anne Rasmussen recounts.

The health crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic will be etched in our collective memory for a long time to come. What is the last pandemic to have made such a mark on history?

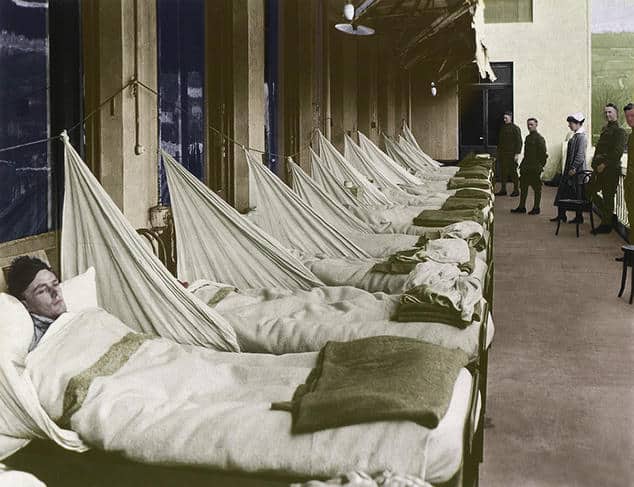

Anne Rasmussen: That would have to be the so-called ‘Spanish’ flu. The first wave, which began in the spring of 1918, was followed by a second, much more deadly spate the following autumn. The situation imposed by the world war, with its constant movements of troops, prisoners and refugees, facilitated the propagation in the warring countries of an already highly contagious respiratory virus. Epidemiologists suspected that, as with coronavirus today, ‘healthy carriers’ – a new concept back then – helped spread it. Indeed, in some villages the flu seemed to appear mysteriously, with no discernable link between any new case and the arrival of an infected person. It was an explosive combination of circumstances.

The earliest assessments of the influenza epidemic by bacteriologists, in the 1920s, estimated the total number of deaths at more than 20 million. However, these analyses underestimate the real toll, which was especially difficult to evaluate in Asia in the absence of public records data. Based on subsequent work by historians, it is now thought that the death rate was more like 50 million, which remains a conservative estimate. That outbreak was unprecedented, not only for its grim tally, but also because it swept across every region of the world with no exception. It was the first pandemic on such a global scale.

A.R.: Yes, in a sense. In fact, it started with the influenza epidemic that preceded the Spanish flu, in 1889-90. At the height of the industrial revolution, when movements among populations were rapidly increasing with the advent of modern transport, people claimed that the flu ‘travelled faster’. Epidemiologists traced its spread from Russia to Europe. It was already being acknowledged that the world was much more interdependent than before, and that what happened in Uzbekistan, for example, could have an impact on a village in France. But even before 1889, Europe had been ravaged by diseases straying beyond their usual territories. After the bubonic plague of the Middle Ages, this happened with yellow fever in 1822 and cholera in 1832, but the transport revolution was the real turning point: as populations gained mobility, epidemics began circulating much more widely.

What strategies were deployed to contain those outbreaks? Was confinement prescribed?

A.R.: For the Spanish flu, the quarantine measures (more so than confinement in the strict sense of the term) that were imposed in Australia, and locally in certain American cities, were not widely adopted in Europe. It was believed, at least in France, that since the disease was caused by a respiratory pathogen, it was no use trying to contain it because it was ‘already present’. Also, in 1918 Europe was still at war. Germany launched a major offensive in the spring, followed by counter-offensives that summer. There was never any question of halting military operations, and troop movements took priority. In addition, during the war, military information on the illness was censored in both France and Germany. No one wanted to risk demoralising – and thus demotivating – the soldiers, or letting information fall into enemy hands.

The first data to be made public came from Spain, a neutral country at the time. For that reason, it was briefly thought that the epidemic had originated there – hence the name ‘Spanish flu’. In other contexts, attempts were made to impose quarantines in a bid to slow the spread of contagion. For example, during the European plague of the 17th century, people avoided contact with the sick and observed ‘containment measures’. Depictions of ‘plague doctors’ in costumes supposed to be impervious to the contagium are well known. Similarly, during the cholera epidemic of 1832, sanitary cordons were set up, manned by military personnel authorised to shoot violators, in an effort to stop the progression of the disease, and people secluded themselves in their homes.

“Containment measures” were already imposed during the European plague epidemics of the 17th century. Physicians wore masks and costumes that were thought to be impervious to the contaminants, as seen in this engraving of “Dr. Schnabel” (“Doctor Beak”) from 1656.

Were the sick systematically quarantined in the Middle Ages or during later scourges?

A.R.: In the Middle Ages, when the first maritime quarantines were instituted in reaction to the black plague, the main purpose was to prevent the arrival of ships, and their suspect cargos, in the ports. All passengers and merchandise were kept in ‘lazarettos’, which were a kind of infirmary-prison, for a maximum of 40 days (the supposed incubation period of the infection). Non-compliance with quarantine measures, in the port of Marseille (southeastern France), was what caused the last major plague in France, in 1720. Rules were sometimes broken because, already in those days, such health precautions could conflict with economic interests. And of course the economy also involved vital supplies for the population – confining those who provided food would have meant everyone starving to death! In the 19th century, the quarantine principle was criticised by some, even during cholera outbreaks, as being contrary to individual freedom. In an age of economic development and free trade, opposition movements denounced these practices as mediaeval, with consequences that could be worse than the contagion.

So there was an economic case against confinement even back then. What about scientific arguments?

A.R.: In the 19th century, the medical world was divided between the ‘contagionists’, who believed (rightly!) that pathogenic agents were transmitted directly by humans, and the ‘infectionists’, in whose view diseases were transmitted via the environment, in particular unhealthy places where miasmas proliferated. According to them, quarantines were ineffective and even harmful, and the best course of action was to make the surroundings healthier, for example by disinfection.

The 19th century also witnessed the first scientific breakthroughs in the field of infections…

A.R.: Absolutely. Starting with the influenza of 1889, researchers tried to figure out what was going on, to understand the aetiology of this epidemic that had claimed so many victims. Samples were collected from flu sufferers with the aim of isolating the germ that caused it – as it had recently been established that each infectious disease corresponds to a specific microorganism. Two main bacteriological schools were in a race to track down the microbe: that of the German physician Robert Koch and the French school headed by Louis Pasteur.

This era marked a turning point: for a long list of devastating infections, including cholera, dysentery and plague, the germ was identified, isolated and grown in vitro to produce the first vaccines. These breakthroughs also provided the scientific basis for protective measures such as disinfection, sterilisation, etc. It was an immense relief for populations that had been living under the threat of age-old contagions. The mortality of certain infectious diseases, and in particular infant mortality, was reduced. Yet these scourges seem like a distant memory and our contemporary societies tend to forget to what extent preventive healthcare and inoculations represented a huge step forward in the fight against epidemics.

On 14 May, 1796, Edward Jenner, a physician in Berkeley, (Great Britain), injected a young boy with pus from cowpox (“vaccine” in French), a benign bovine disease related to the smallpox that the child had contracted. The case is considered the first instance of vaccination.

Over the centuries, which ones have caused the most upheaval in the societies that were affected?

A.R.: It goes without saying that major outbreaks like the Spanish flu left traumatic memories, with societies in mourning, but generally speaking the page is turned rather quickly. The afflictions that have had the deepest impact on societies are the endemic diseases that mark individual and collective existences, like tuberculosis and syphilis. They were genuine social scourges that affected young people – and thus a country’s workforce and birth rate (depopulation was a real obsession in late 19th-century France). At the time, some thought that syphilis was transmissible to the next generation and could therefore cause the degeneration of the entire population. These were the ailments that people were most concerned about in everyday life, and that led to large-scale initiatives, like so many Marshall Plans for public health.

Starting at the end of World War I, health education campaigns and fundraising drives were organised to combat tuberculosis. Governments and foundations (like the Rockefeller Foundation) invested heavily in the effort. After the Second World War, programmes were launched on an international scale to eradicate contagions like smallpox, a condition that left its victims disfigured. To eliminate it, the World Health Organization implemented a grid system to identify every smallpox case, down to the last one, until the virus disappeared completely. And it worked! Today, smallpox exists only in collections held in closely guarded laboratories. Following these encouraging successes, in the late 1970s people earnestly believed that infectious diseases were a thing of the past and would never afflict humankind again.

Then, in the early 1980s, the appearance of HIV dashed that optimism. After being reported in the summer of 1981 by the Centers for Disease Control in the United States, based on a clinical description, its existence was confirmed by a large-scale epidemiological survey in 1982. The hypothesis of a new disease, AIDS, was attested by the identification in 1983 of a retrovirus, whose discovery was claimed by both French and US research teams. The screening tests, which became available to the public in 1985, drew attention to the existence of seropositivity, a latency phase that seemed to precede the onset of the illness, which attacks the immune system. From a historical perspective, the timeline of these discoveries was very short. Yet four decades later, these procedures have been significantly accelerated since the emergence of Covid-19.

Now that the old diseases have been eradicated, we are confronted with new ones. Are they linked to the rapid growth of the world population in recent decades?

AR: It is true that SARS-CoV-2, which appeared in China in December 2019, followed MERS-CoV, which emerged in Saudi Arabia in 2012, and was itself preceded by SARS-CoV-1, whose first cases were recorded in China in November 2002. Before that, the entire world was terrified of Ebola, which started in Africa. I’m not sure these new viruses are linked to population growth. Perhaps they have something to do with our lifestyles. Some people blame, for example, the disruption of ecosystems, like deforestation, which deprives wild animals of their natural habitats and brings them into closer contact with human beings, thus facilitating interspecies transmission.

This is quite possible, but I also think that we are shocked when a new viral disease appears because, once again, in the late 1970s we genuinely thought that we had vanquished them all. Yesterday’s confidence may explain today’s perplexity. And yet there are a great many viruses that interact with humans and always will.

Robert Koch, the German physician who discovered the bacillus responsible for tuberculosis in 1882. Later, the work by Calmette and Guérin in France led to the development of BCG (for “Bacillus Calmette-Guerin”) vaccine in the 1920s, a precious weapon in the fight against a scourge that took a heavy toll among the young.

In 2020, we find ourselves in a situation not unlike that of 1918, dealing with an unfamiliar pathogen…

AR: Yes, but we are considerably less ignorant now. The Covid-19 genome was sequenced in three days. We are already getting to know it well, whereas the people of 1918 lived through the entire pandemic without really understanding its cause. Fortunately, in dealing with modern-day epidemics, the state of health and hygiene is much improved. We have very effective healthcare systems, as proven by the resuscitation techniques now available, even though the number of beds is insufficient for a crisis, backed by social protection mechanisms, at least in the wealthy countries. We enjoy a whole therapeutic arsenal – not specifically against SARS-CoV-2, unfortunately, but there are antivirals as well as antibiotics that, although they have no effect against viruses, can limit the associated bacterial infections. And researchers are already working on a vaccine. Among those clamouring for its urgent development, there are no doubt many people who do not get flu jabs, or who refuse to have their children inoculated. This is a good time to remember that it’s vaccines that have saved us from so many diseases whose disastrous consequences are well documented in history.

Footnotes

- 1.Historian and head of the Centre Alexandre Koyré (CNRS / EHESS / MNHN).

- 2.Medical discipline that investigates the causes of diseases.

- 3.German physician who gave his name to the bacillus responsible for tuberculosis, which he discovered.

The French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) is a public-funded institution that covers all scientific disciplines, from the humanities and social sciences to biological sciences, nuclear and particle physics, information sciences, engineering and systems, physics, mathematical sciences, chemistry, Earth sciences and astronomy, and ecology and the environment.