According to new analysis from political scientists at the University of Bath however, the pervasive use of the term – also termed ‘populist hype’ – has had serious consequences in helping to legitimise certain kinds of politics, most notably the far right.

Writing in the journal Politics, the researchers from the Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies at Bath, analysed coverage from The Guardian’s ‘new populism’ six-month series which ran from November 2018 and was designed to explore the term from different vantages.

In their critique they argue that ‘populism’ has fast-become a catch-all term attributed to an array of different phenomena and political standpoints – from a jazz musician and the film Sweet Home Alabama, to nationalism, protectionism of an economy and racism. The replacement of more accurate descriptions with ‘populism’, as well as the lack of care in it use, has muddied the waters as to what exactly we are talking about.

Most commonly though, ‘populism’ is attributed to far-right politics and this brings its own set of problems. The researchers warn that ‘populism’ has too often been reported on as a response to pent-up demands from ‘the people’, while ignoring the role of the media and politicians in its growth in popularity, both as a term and type of politics. Beyond the lack of clarity, it has also created or at least exaggerated links between ‘the people’ and the far right in particular, lending elitist and minoritarian politics a veneer of democratic legitimacy.

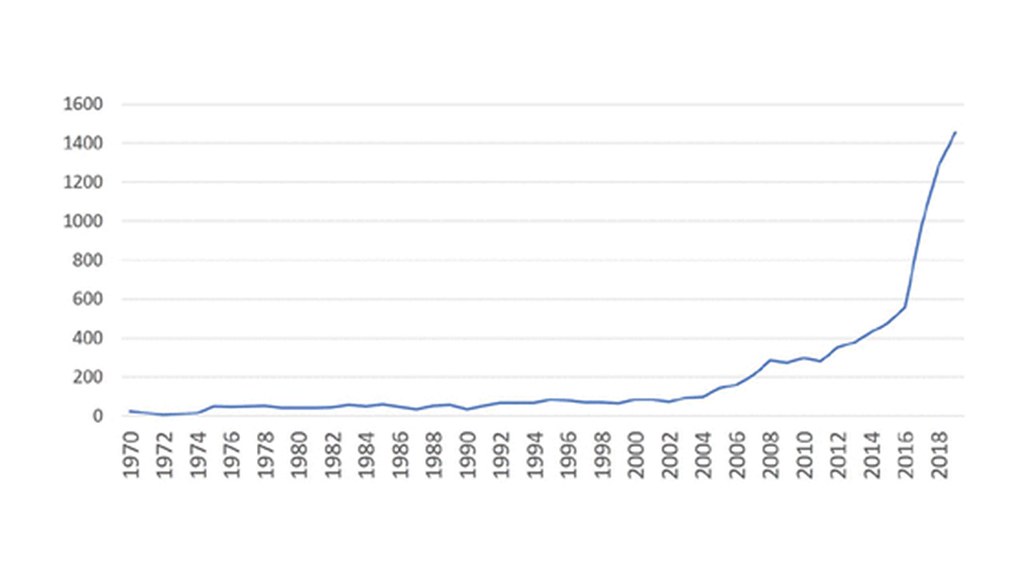

Focusing on The Guardian’s new populism series, they suggest this was a missed opportunity to provide clarity on a term and type of politics which have shaped our current political age, but not always as we think it has. Highlighting one article from that series in particular – headline: ‘Why is populism suddenly all the rage?’; sub-header: ‘In 1998, about 300 Guardian articles mentioned populism. In 2016, 2,000 did. What happened? – they suggest the piece failed to acknowledge that to a large extent the massive upsurge in use was also a result of editorial choices.

Dr Aurelien Mondon of the University of Bath’s Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies explains: “While Trump, Orban or Le Pen can indeed make use of populist discourse by pitting a constructed version of a ‘people’ against an ‘elite’, this is only a small part of their politics, which draw more from other larger ideologies and ideas such as ultra-conservatism, racism, or even fascism. While populism can help us understand the discursive nature of such politics, it does little on its own to explain their broader meaning and potential consequences.”

Co-author Katy Brown also of the Department of Politics, Languages & International Studies, says: “This is by no means a problem unique to The Guardian, and there were many excellent contributions to its ‘the new populism’ series, but the problems we identify illustrate the importance of critical and careful use of terminology.

“The simplification and trivialisation of the term ‘populist’ has blurred meanings between phenomena such as nativism, nationalism, protectionism and racism which has helped to legitimate them by avoiding deeper scrutiny of so-called ‘populist’ policies.”

Their critique is not reserved to the media. In their analysis they also highlight a huge upswing in the use of the term ‘populism’ throughout academic literature, some of it, they argue, without sufficient critical reflection or care taken over how it has been applied.

Graph showing the number of publications containing the term ‘populism/t’ in the title, abstract, or keywords on the Web of Science database by year.

Dr Mondon adds: “Academics have a real role to play in helping people make sense of society and politics, and the work done on populism is key to this. However, it is essential that we reflect upon the impact our work has and how it is interpreted in wider circles. Hopefully, our article makes one such contribution.”

The study

- Populism, the media, and the mainstreaming of the far right: The Guardian’s coverage of populism as a case study is published via the Political Studies Association Journal Politics. DOI: 10.1177/0263395720955036.