Identifying and isolating individuals who may be contagious with the coronavirus is key to limiting the spread of the disease. But even months into the pandemic, many patients are still waiting days to receive COVID-19 test results.

Scientists at UC Berkeley and Gladstone Institutes have developed a new CRISPR-based COVID-19 diagnostic test that, with the help of a smartphone camera, can provide a positive or negative result in 15 to 30 minutes. Unlike many other tests that are available, this test also gives an estimate of viral load, or the number of virus particles in a sample, which can help doctors monitor the progression of a COVID-19 infection and estimate how contagious a patient might be.

“Monitoring the course of a patient’s infection could help health care professionals estimate the stage of infection and predict, in real time, how long is likely needed for recovery and how long the individual should quarantine,” said Daniel Fletcher, a professor of bioengineering at Berkeley and one of the leaders of the study.

The technique was designed in collaboration with Dr. Melanie Ott, director of the Gladstone Institute of Virology, as well as Berkeley professor Jennifer Doudna, who is a senior investigator at Gladstone, president of the Innovative Genomics Institute and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Doudna recently won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for co-discovering CRISPR-Cas genome editing, the technology that underlies this work.

Most COVID-19 diagnostic tests rely on a method called PCR, short for polymerase chain reaction, which searches for pieces of the SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in a sample. These PCR tests work by first isolating the viral RNA, then converting the RNA into DNA and then “amplifying” the DNA segments — making many identical copies — so that the segments can be more easily detected.

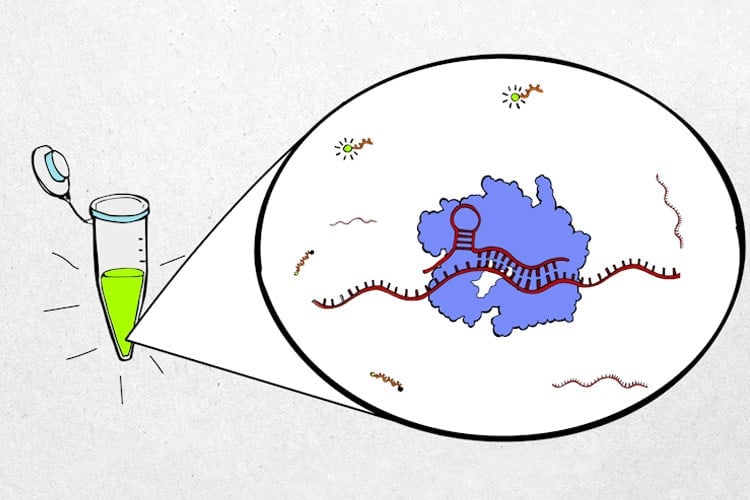

The new diagnostic test takes advantage of the CRISPR Cas13 protein, which directly binds and cleaves RNA segments. This eliminates the DNA conversion and amplification steps and greatly reduces the time needed to complete the analysis.

“One reason we’re excited about CRISPR-based diagnostics is the potential for quick, accurate results at the point of need,” Doudna said. “This is especially helpful in places with limited access to testing or when frequent, rapid testing is needed. It could eliminate a lot of the bottlenecks we’ve seen with COVID-19.”

In the test, CRISPR Cas13 proteins are “programmed” to recognize segments of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA and then combined with a probe that becomes fluorescent when cleaved. When the Cas13 proteins are activated by the viral RNA, they start to cleave the fluorescent probe. With the help of a handheld device, the resulting fluorescence can be measured by the smartphone camera. The rate at which the fluorescence becomes brighter is related to the number of virus particles in the sample.

“Recent models of SARS-CoV-2 suggest that frequent testing with a fast turnaround time is what we need to overcome the current pandemic,” Ott said. “We hope that with increased testing, we can begin to reopen economies and protect the most vulnerable populations.”

Now that the CRISPR-based assay has been developed for SARS-CoV-2, it could be modified to detect RNA segments of other viral diseases, like the common cold, influenza or even human immunodeficiency virus. The team is currently working to package the test into a device that could be made available at clinics and other point-of-care settings and that one day could even be used in the home.

“The eventual goal is to have a personal device, like a mobile phone, that is able to detect a range of different viral infections and quickly determine whether you have a common cold or SARS-Cov-2 or influenza,” Fletcher said. “That possibility now exists, and further collaboration between engineers, biologists and clinicians is needed to make that a reality.”