New research from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health shows that waxing and waning COVID-19 case counts traveled across North American county, state and country borders with seemingly little regard for politics and public health mandates, much like a storm can sweep the continent.

“This really is remarkable,” said Donald Burke, Distinguished University Professor of Health Science and Policy, Epidemiology and former dean of Pitt Public Health. “Throughout the pandemic, it’s been common to hear reports that there’s a surge of COVID-19 in a specific state. But if you take a step back, you see that it’s generally not just the state having the surge—it’s a whole region, such as the Gulf states of both the U.S. and Mexico, or Michigan and several provinces in Canada.”

Because the findings could have important public health ramifications, Burke and Pitt Public Health colleagues Hawre Jalal, assistant professor, and Kyueun Lee, postdoctoral associate, posted their discovery to medRxiv, a preprint journal, and announced the results ahead of peer-reviewed publication.

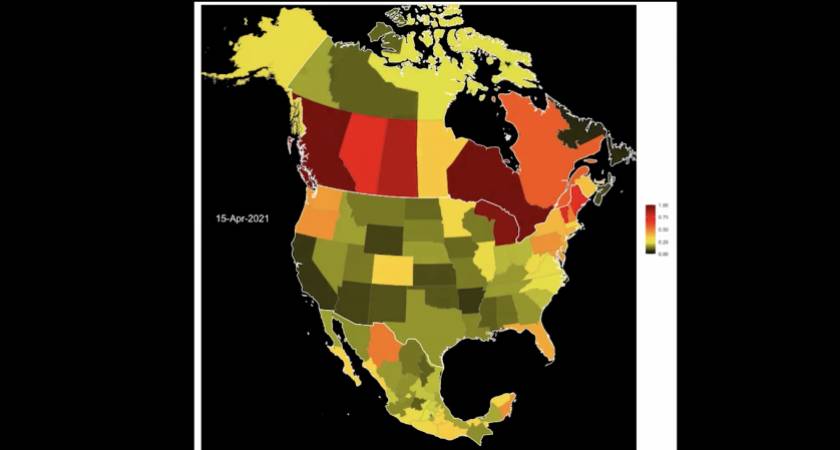

The team mapped COVID-19 case counts from February 2020 into May 2021 in the states of Mexico and the U.S., as well as the provinces and territories of Canada. They did the same mapping for counties throughout the United States. And then they animated it across time.

The animations show how surges flow across one county to another, crossing state borders without hesitation. In North America, cases cross into Canada and Mexico and back to the U.S. For example, when Michigan was experiencing a surge in spring 2021, so were the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec and several northeastern U.S. border states.

Mexico began to have higher case counts in summer 2020 that traveled into the southern U.S. and moved northward. After a sustained drop through spring 2021, Mexico is again experiencing a growing caseload—making the southern U.S. and its low COVID-19 vaccination rates a potential tinderbox.

“We do not know what is causing these patterns—and that is a major reason why we are sharing these findings now, rather than waiting for peer review. We want academics from other disciplines, as well as the public, to make suggestions,” said Jalal. “We strongly suspect this is related to weather. Movement of the epidemic waves probably has more to do with movement of weather patterns than movement of people.”

“These are not subtle patterns,” said Burke. “If we can figure out what is driving these continental-scale epidemic waves, we should be able to forecast surges of COVID-19 and prevent them from occurring.”