Working with a “rare and rich” digital archive of 19th-century Choctaw language court documents, Penn State history scholars and graduate students are partnering with linguists from the University of Florida on a multi-faceted initiative called the Choctaw Language and History Workshop.

The project, which promotes a new model for graduate students studying Native American history, will have multiple deliverables, including several scholarly articles and a Choctaw language dictionary developed in consultation with the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

Assembled during the summer of 2020 by Penn State’s Christina Snyder, McCabe Greer Professor of the American Civil War Era, and George Aaron Broadwell, Elling Eide Professor of Anthropology and chair of linguistics at the University of Florida, the project team is comprised of Native and non-Native historians and linguists who specialize in studying Native nations of the American South.

Joining Snyder on the Penn State research team are Julie Reed, associate professor of history and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, and two doctoral students, Edward Green and Jamie Henton, both of whom focus on Choctaw history. A doctoral student from the University of North Carolina and a junior research fellow from Christ’s College, University of Cambridge, round out the project team.

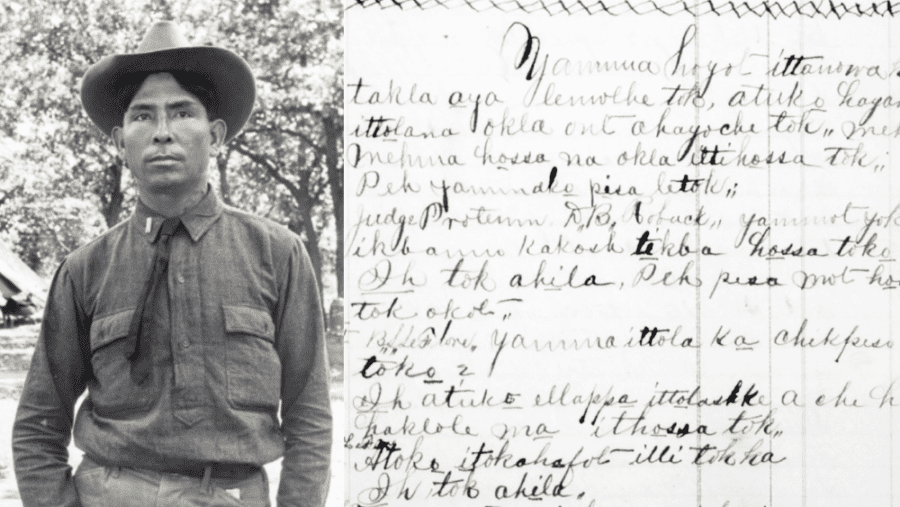

“With the pandemic in full swing, Aaron [Broadwell] and I wanted to create an interdisciplinary project that would benefit our graduate mentees, be feasible over Zoom, and use a shared archive,” Snyder said, adding that the participants have been meeting weekly via Zoom. “We are translating and analyzing a rarely used manuscript collection containing thousands of Choctaw-language court documents from the 1800s.”

Originally from what is now Mississippi, the Choctaws are one of the largest Native American nations in the United States today. Forced to leave their homelands in the mid-1830s as a result of Andrew Jackson’s Indian removal policy, the majority of Choctaws relocated to Oklahoma, though some managed to remain in Mississippi. The larger group is called the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Those who remained in Mississippi call themselves the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

“The Choctaw Nation and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians each have a rich history, and they remain strong nations today,” Snyder said. “And while nearly every Choctaw speaks English today, there are thousands and thousands who have some degree of fluency in their native language. In fact, some still have Choctaw as their first language, and they are making a huge push to revitalize the language and teach it in schools.”

Despite the many thousands of Choctaw speakers, however, the majority of 19th-century Choctaw documents were written by tribal elites and missionaries and fail to include the more informal, everyday words and phrases used by most.

“By looking at the transcriptions of county court cases and local disputes, we get to read what people actually said, how they actually talked,” Snyder said. “The linguists comment on what they think is interesting, and the historians comment on what we think is interesting, and we’re trying to channel that into several different publications.”

One of those publications is a modern Choctaw dictionary, which is the main focus of Broadwell and his fellow linguists. But how can 19th-century documents inform a 21st-century dictionary?

“Most modern dictionaries rely on a large collection of natural language materials to understand how words are used in context,” explained Broadwell, who has worked extensively with the Choctaws, several of whom are collaborating on the project. “In addition to checking with current speakers, lexicographers want to look at many instances of words used over time and in different texts to be sure that the dictionary captures all the subtleties correctly. For this reason, our modern Choctaw dictionary benefits from looking at how Choctaw words were used in earlier times.”

Pushing the boundaries of Native American research

“The Choctaw Language and History Workshop is one of the many ways our core faculty in Native American history are pushing the boundaries for innovative and interdisciplinary research on subjects that have never been adequately studied in the past,” said Michael Kulikowski, Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of History and Classics and head of the Penn State Department of History. “I’m particularly pleased by the way the project brings together faculty from several different institutions, all with great strengths in the sub-discipline, and even more by the way graduate students are being involved as foundational members of the enterprise.”

“This project provides a new model of graduate training by emphasizing the importance of Native language documents and understanding Native languages,” Snyder echoed, adding that Green and Henton will be taking intensive Choctaw language courses over the summer. “Scholars have relied too heavily on European language sources. We know, and what we’re really interested in with this project, is that working with indigenous language sources is going to tell us something about the Choctaws that is different from what we might expect.”

With what they are learning from the archival translations, Snyder and her collaborators are planning several co-written articles based on the Choctaw archive. One focuses on the criminalization of “whooping,” a diverse cultural practice among the Choctaws and other Native nations, which non-Natives tend to associate exclusively with warfare. Another examines early court records that seemed to continue to favor matrilineal property rights — the Choctaws traditionally trace their ancestry through the mother’s line — which were being eroded over time in favor of paternal power.

“Ultimately, the project is about how Native-centered stories can change our perspective on America’s past, present and future,” Snyder concluded. “In the case of these late 19th-century court records, we are investigating an understudied period on the other side of the Trail of Tears. By then, the Choctaw Nation had survived Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal policy, the devastation of the Civil War, and ongoing white efforts to seize land and other resources. Through the court cases, we see the strains of these assaults but also the resilience of the Choctaw Nation, the strength of their judicial system, and the determination of everyday Choctaw people to maintain peace, property and their way of life.”