Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, reveal a potential mechanism behind the regulation of insulin sensitivity through deep-sleep brain waves, offering hope for improved blood sugar control and potential therapeutic interventions for diabetes.

Researchers have long recognized the association between inadequate sleep and an increased risk of diabetes. However, the underlying reasons remained elusive. Now, a team of sleep scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, has made significant progress in unraveling this mystery. Their recent findings shed light on a potential mechanism that explains how deep-sleep brain waves during the night can impact the body’s sensitivity to insulin, subsequently enhancing blood sugar control the following day.

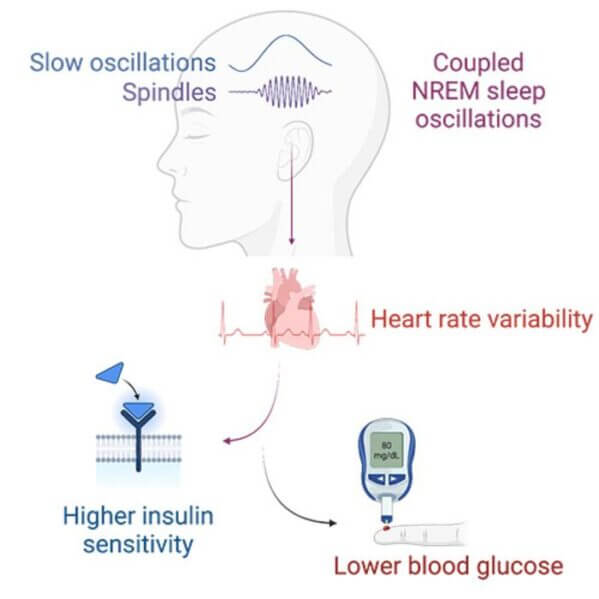

According to Matthew Walker, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at UC Berkeley and the senior author of the study, “These synchronized brain waves act like a finger that flicks the first domino to start an associated chain reaction from the brain, down to the heart, and then out to alter the body’s regulation of blood sugar.” The combination of two specific brain waves, known as sleep spindles and slow waves, predicts an increase in the body’s sensitivity to insulin, leading to lower blood glucose levels.

The implications of this research are particularly significant, as sleep is a modifiable lifestyle factor that can potentially be incorporated into therapeutic approaches for individuals with high blood sugar or Type 2 diabetes.

The study’s authors also highlighted an additional benefit derived from these deep-sleep brain waves. Vyoma D. Shah, a researcher at the Center for Human Sleep Science and co-author of the study, stated, “Beyond revealing a new mechanism, our results also show that these deep-sleep brain waves could be used as a sensitive marker of someone’s next-day blood sugar levels, more so than traditional sleep metrics.” This discovery suggests a novel and non-invasive tool for mapping and predicting blood sugar control—deep-sleep brain waves.

The team’s findings were recently published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

While previous research had primarily focused on the role of deep-sleep brain waves in learning and memory, this new study builds upon a 2021 rodent study to uncover a previously unrecognized role for these combined brain waves in humans, specifically in blood sugar management.

To investigate this further, the UC Berkeley researchers examined sleep data from a group of 600 individuals. They discovered that the coupling of these particular deep-sleep brain waves could predict glucose control the following day, independent of factors such as age, gender, and sleep duration and quality. Raphael Vallat, a postdoctoral fellow at UC Berkeley and co-author of the study, explained, “That indicates there is something uniquely special about the electrophysiological quality and coordinated ballet of these brain oscillations during deep sleep.”

The next step for the researchers involved exploring the mechanism through which these deep-sleep brain waves communicate with the body to regulate blood glucose. Their findings revealed a series of steps that shed light on this connection. The team observed that stronger and more frequent coupling of the deep-sleep brain waves predicted a shift in the body’s nervous system state toward a more calming and restful state, known as the parasympathetic nervous system. This change was measured using heart rate variability as a proxy for stress levels.

Furthermore, the researchers discovered that this switch to the calming branch of the nervous system during deep sleep also led to increased sensitivity to insulin, the hormone responsible for glucose regulation. Insulin prompts cells to absorb glucose from the bloodstream, preventing dangerous spikes in blood sugar levels. This finding holds particular significance for individuals managing hyperglycemia and Type 2 diabetes.

“In the electrical static of sleep at night, there is a series of connected associations, such that deep-sleep brain waves telegraph a recalibration and calming of your nervous system the following day,” explained Matthew Walker. “This rather marvelous associated soothing effect on your nervous system is then associated with a reboot of your body’s sensitivity to insulin, resulting in a more effective control of blood sugar the next day.”

To validate their findings, the researchers replicated the study with a separate group of 1,900 participants. The consistent results bolstered their confidence in the research, although they remain cautious and await replication by other scientists.

The potential clinical significance of this research is immense, considering the challenges patients face in adhering to existing diabetes treatments and recommended lifestyle changes. Sleep, however, is a largely painless experience for most individuals. While sleep alone cannot serve as a magic cure-all, the discovery of new technologies capable of safely modulating brain waves during deep sleep opens up possibilities for better blood sugar management. This breakthrough brings hope to those affected by diabetes and paves the way for future therapeutic interventions.