A method by Rice University researchers to model the way proteins fold – and sometimes misfold – has revealed branching behavior that may have implications for Alzheimer’s and other aggregation diseases.

Results from the research will appear online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

In an earlier study of the muscle protein titin, Rice chemist Peter Wolynes and his colleagues analyzed the likelihood of misfolding in proteins, in which domains – discrete sections of a protein with independent folding characteristics – become entangled with like sequences on nearby chains. They found the resulting molecular complexes called “dimers” were often unable to perform their functions and could become part of amyloid fibers.

This time, Wolynes and his co-authors, Rice postdoctoral researcher Weihua Zheng and graduate student Nicholas Schafer, modeled constructs containing two, three or four identical titin domains. They discovered that rather than creating the linear connections others had studied in detail, these proteins aggregated by branching; the proteins created structures that cross-linked with neighboring proteins and formed gel-like networks that resemble those that imbue spider silk with its remarkable flexibility and strength.

“We’re asking with this investigation, What happens after that first sticky contact forms?” Wolynes said. “What happens if we add more sticky molecules? Does it continue to build up further structure out of that first contact?

“It turned out this protein we’ve been investigating has two amyloidogenic segments that allow for branch structures. That was a surprise,” he said.

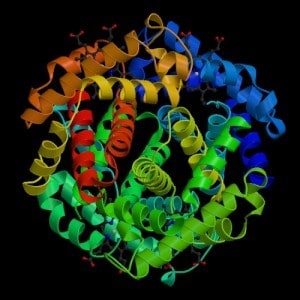

The researchers used their AWSEM (Associative memory, Water-mediated Structure and Energy Model) program to analyze how computer models of muscle proteins interact with each other, particularly in various temperatures that determine when a protein is likely to fold or unfold.

The program relies on Wolynes’ groundbreaking principle of minimal frustration to determine how the energy associated with amino acids, bead-like elements in a monomer chain, determines their interactions with their neighbors as the chain folds into a useful protein.

Proteins usually fold and unfold many times as they carry out their tasks, and each cycle is an opportunity for it to misfold. When that happens, the body generally destroys and discards the useless protein. But when that process fails, misfolded proteins can form the gummy amyloid plaques often found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

The titin proteins the Rice team chose to study are not implicated in disease but have been well-characterized by experimentalists; this gives the researchers a solid basis for comparison.

“In the real muscle protein, each domain is identical in structure but different in sequence to avoid this misfolding phenomenon,” Wolynes said. So experimentalists studying two-domain constructs made the domains identical in every way to look for the misfolding behavior that was confirmed by Rice’s earlier calculations. That prompted Wolynes and his team to create additional protein models with three and four identical domains.

“The experiments yield coarse-grained information and don’t directly reveal detail at the molecular level,” Schafer said. “So we design simulations that allow us to propose candidate misfolded structures. This is an example of how molecular models can be useful for investigating the very early stages of aggregation that are hard to see in experiments, and might be the stages that are the most medically relevant.”

“We want to get the message across that this is a possible scenario for misfolding or aggregation cases — that this branching does exist,” Zheng added. “We want experimentalists to know this is something they should be looking for.”

Wolynes said the lab’s next task is to model proteins that are associated with specific diseases to see what might be happening at the start of aggregation. “We have to investigate a wider variety of structures,” he said. “We have no new evidence these branching structures are pathogenic, but they’re clearly an example of something that happens that has been ignored until now.

“I think this opens up new possibilities in what kind of structures we should be looking at,” he said.

The National Institute of General Medical Sciences, one of the National Institutes of Health, and the D.R. Bullard-Welch Chair at Rice University supported the research. Wolynes is the Bullard-Welch Foundation Professor of Science and a professor of chemistry and a senior scientist with the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics at Rice. The researchers utilized the Data Analysis and Visualization Cyberinfrastructure (DAVinCI) supercomputer supported by the National Science Foundation and administered by Rice’s Ken Kennedy Institute for Information Technology.