New MIT nanoparticles offer best-ever gene silencing, could help treat liver diseases.

Inspired by tiny particles that carry cholesterol through the body, MIT chemical engineers have designed nanoparticles that can deliver snippets of genetic material that turn off disease-causing genes.

This approach, known as RNA interference (RNAi), holds great promise for treating cancer and other diseases. However, delivering enough RNA to treat the diseased tissue, while avoiding side effects in the rest of the body, has proven difficult.

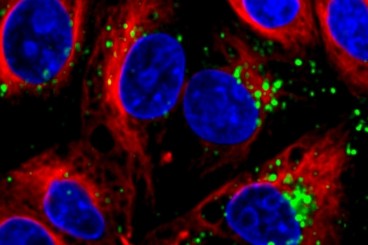

The new MIT particles, which encase short strands of RNA within a sphere of fatty molecules and proteins, silence target genes in the liver more efficiently than any previous delivery system, the researchers found in a study of mice.

“What we’re excited about is how it only takes a very small amount of RNA to cause gene knockdown in the whole liver. The effect is specific to the liver — we get no effect in other tissues where you don’t want it,” says Daniel Anderson, the Samuel A. Goldblith Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering and a member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research.

Anderson is senior author of a paper describing the particles in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences the week of Feb. 10. Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor at MIT, is also an author.

The research team, which included scientists from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, also found that the nanoparticles could powerfully silence genes in nonhuman primates. The technology has been licensed to a company for commercial development.

Natural inspiration

RNA interference is a naturally occurring phenomenon that scientists have been trying to exploit since its discovery in 1998. Snippets of RNA known as short interfering RNA (siRNA) turn off specific genes inside living cells by destroying the messenger RNA molecules that carry DNA’s instructions to the rest of the cell.

Scientists hope this approach could offer new treatments for diseases caused by single mutations, such as Huntington’s disease, or cancer, by blocking mutated genes that promote cancerous behavior. However, developing RNAi therapies has proven challenging because it is difficult to deliver large quantities of siRNA to the right location without causing side effects in other tissues or organs.

In previous studies, Anderson and Langer showed they could block multiple genes with small doses of siRNA by wrapping the RNA in fatlike molecules called lipidoids. In their latest work, the researchers set out to improve upon these particles, making them more efficient, more selective, and safer, says Yizhou Dong, a postdoc at the Koch Institute and lead author of the paper.

“We really wanted to develop materials for clinical use in the future,” he says. “That’s our ultimate goal for the material to achieve.”

The design inspiration for the new particles came from the natural world — specifically, small particles known as lipoproteins, which transport cholesterol and other fatty molecules throughout the body.

Like lipoprotein nanoparticles, the MIT team’s new lipopeptide particles are spheres whose outer membranes are composed of long chains with a fatty lipid tail that faces into the particle. In the new particles, the head of the chain, which faces outward, is an amino acid (the building blocks of proteins). Strands of siRNA are carried inside the sphere, surrounded by more lipopeptide molecules. Molecules of cholesterol embedded in the membrane and an outer coating of the polymer PEG help to stabilize the structure.

The researchers tuned the particles’ chemical properties, which determine their behavior, by varying the amino acids included in the particles. There are 21 amino acids found in multicellular organisms; the researchers created about 60 lipopeptide particles, each containing a different amino acid linked with one of three chemical groups — an acrylate, an aldehyde, or an epoxide. These groups also contribute to the particles’ behavior.

David Putnam, an associate professor of biomedical engineering at Cornell University, says he is impressed with the team’s approach to mimicking how the body transports fatty molecules with lipoprotein particles.

“They hijacked that machinery and made something that looks like the lipoprotein structures and will carry siRNA straight to the liver. They’re building on Mother Nature and making it as efficient as possible,” says Putnam, who was not part of the research team.

Targeted strike

The researchers then tested the particles’ ability to shut off the gene for a blood clotting protein called Factor VII, which is produced in the liver by cells called hepatocytes. Measuring Factor VII levels in the bloodstream reveals how effective the siRNA silencing is.

In that initial screen, the most efficient particle contained the amino acid lysine linked to an epoxide, so the researchers created an additional 43 nanoparticles similar to that one, for further testing. The best of these compounds, known as cKK-E12, achieved gene silencing five times more efficiently than that achieved with any previous siRNA delivery vehicle.

In a separate experiment, the researchers delivered siRNA to block a tumor suppressor gene that is expressed in all body tissues. They found that siRNA delivery was very specific to the liver, which should minimize the risk of off-target side effects.

“That’s important because we don’t want the material to silence all the targets in the human body,” Dong says. “If we want to treat patients with liver disease, we only want to silence targets in the liver, not other cell types.”

In tests in nonhuman primates, the researchers found that the particles could effectively silence a gene called TTR (transthyretin), which has been implicated in diseases including senile systemic amyloidosis, familial amyloid polyneuropathy, and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy.

The MIT team is now trying to learn more about how the particles behave and what happens to them once they are injected, in hopes of further improving the particles’ performance. They are also working on nanoparticles that target organs other than the liver, which is more challenging because the liver is a natural destination for foreign material filtered out of the blood.

The research was funded by Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and the National Institutes of Health.