HIV-positive women respond well to a vaccine against the human papillomavirus (HPV), even when their immune system is struggling, according to newly published results of an international clinical trial. The study’s findings counter doubts about whether the vaccine would be helpful, said the Brown University medical professor who led the study. Instead, the data support the World Health Organization’s recommendation to vaccinate women with HIV.

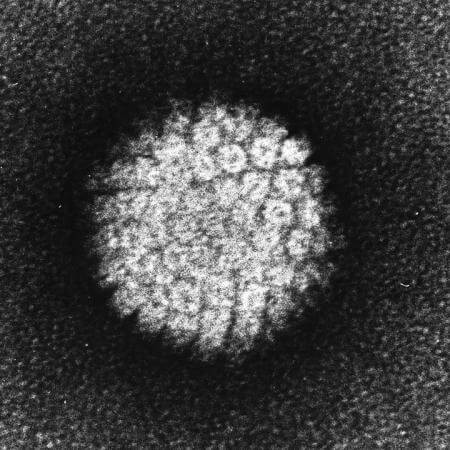

HPV causes cervical and other cancers. The commonly used HPV vaccine Gardasil had not been tested in seriously immune-suppressed women with HIV, said Dr. Erna Milunka Kojic, associate professor of medicine at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and The Miriam Hospital. Despite the WHO recommendation, she said, skeptics have wondered whether the vaccine would be safe and helpful for women with weakened immune systems who were already likely to have been exposed to HPV through sex. Vaccines are often less effective in HIV-positive people.

To address that debate, Kojic’s study, dubbed “AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 5240,” measured the safety and immune system response of the vaccine in HIV-positive women aged 13 to 45 with a wide range of immune statuses. In the vast majority of the 315 volunteers who were vaccinated at sites in the United States, Brazil, and South Africa, the vaccine built up antibodies against HPV and posed no unusual safety issues during the 28 weeks they were each involved.

“The vaccine works for HIV-infected women in terms of developing antibodies,” Kojic said.

Co-author Dr. Susan Cu-Uvin, professor of public health and of obstetrics and gynecology at Brown, said women with HIV are especially susceptible to cervical cancer from HPV because their weakened immune systems are less able to clear the virus. That makes vaccinating HIV-positive women especially important, so long as it’s safe and they respond.

Response across the board

To investigate that response in the context of HIV, the study grouped women by their CD4 cell count, a measure of immune system health. Group A had CD4 counts above 350, group B rested between 200 and 350. Group C was composed of women with counts below 200, the defining level of AIDS for which response to an HPV vaccine had not yet been studied.

Gardasil is a “quadrivalent” vaccine, in that it protects against four types of HPV (6, 11, 16, and 18). Each group in the study, therefore, had four measures of “seroconversion,” or the buildup of a significant army of antibodies against each type of HPV. The researchers determined that seroconversion in at least 70 percent of patients for each HPV type would define success.

They exceeded that mark in every group for every type, according to the data published in advance online in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“Seroconversion proportions at week 28 among women in CD4 stratum A were 96 percent, 98 percent, 99 percent, and 91 percent for HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 respectively; in stratum B, 100 percent, 98 percent, 98 percent, and 85 percent; and in stratum C, 84 percent, 92 percent, 93 percent and 75 percent for each type respectively,” the authors wrote.

Seroconversion rates were clearly lower for women with the weakest immune systems, but still high enough to be worthwhile, Kojic said. And although some of the women in the study had already been exposed to at least one type of HPV, only 1 in 25 had been exposed to all four, suggesting that even older, sexually active women can benefit from vaccination.

The extent of the benefit, she acknowledged, is not yet clear because the trial did not measure the vaccine’s efficacy in preventing cancers. It only measured safety and the number of patients who had the desired immune system response. But that response has been shown to be effective in other studies of other populations of women.

What is clear from the study is that the vaccine produced no more side effects or problems than any vaccine typically does.

“Comparing vaccine reactions, this is a very safe vaccine,” Kojic said. “It doesn’t have any systemic side effects among these women who are already taking medicine for other conditions.”

Kojic said she hopes that by confirming that women with HIV are responsive to the vaccine without unusual adverse effects, more doctors will vaccinate HIV-positive patients.

In addition to Kojic and Cu-Uvin, other authors on the paper are co-corresponding author Michelle Cespedes of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, Minhee Kang, Triin Umbleja, Catherine Godfrey, Reena Allen, Cynthia Firnhaber, Beatriz Grinsztejn, Joel Palefsky, Jennifer Webster-Cyriaque, Alfred Saah, and Judith Aberg.

The study was funded by The National Institutes of Health (grant: UM1AI1068636). Kojic and Cu-Uvin reported no conflicts of interest but some co-authors, including Saah, who works for Gardasil-maker Merck, disclosed ties to the company.

I feel that the previous comments adequately explore the main points of this article. It is indeed a major break through in sustaining the health by aiding the compromised immune systems of HIV+ woman in order to prolong life.

Furthermore the 315 patients on which the results are based is not a very large representation of the extremely large HIV+ population and i too think that more trials would be prudent before administering the vaccine to all HIV+ woman.

I would like to branch onto another topic of thought regarding HIV/AIDS regarding a vaccine or cure for HIV/AIDS itself.

A rather radical opinion is that if a vaccine for HIV or AIDs was found, pharmaceutical companies would not allow its release because they will profit more selling ARV’s to patients for the duration of their lives – and to more patients as it spreads- than curing a patient once.

They make millions every year from selling antiretrovirals, why would they release something that would stop this continuous, reliable flow of income?

I am not denying that it is a liberal thought, but even though it is unethical and immoral, money has a large influence in this capitalist society.

It has been said that HIV+ people are prone to many viruses because vaccines are often less effective in them but this is a very fascinating study that shows otherwise. I have always believed all women should get the HPV vaccine but was just concerned about those living with HIV .I agree with Katie S. Mall however that this evidence cannot be fully accepted because the sample size was very small considering the number of females we have in the world. It has also been proven that as human beings we respond differently to vaccines. This research however is very interesting and I think it could be developed further. Another study can look into measuring the vaccine’s efficiency now that we know a little bit about its safety. This is a very enlightening study above all.

I found the blog posting very informative and convincing. Initially however, I agreed with skeptics that it spoke about. Before reading about the international trial, I was under the impression that HIV-positive patients suffered from very weak immune systems and thus, by administering a vaccine, it seemed harmful as they bodies would not be able to produce antibodies to fight against it. The trial revealed that HIV positive women are able to develop antibodies despite having weaker immune systems which is a major scientific breakthrough. Each group’s seroconversion levels in the study exceeded expectations and revealed the effectiveness of the Garadsil vaccine which the posting mentions. Despite the results of the trial, I would think that more trials should be conducted before doctors are encouraged to vaccinate HIV-positive patients as perhaps some patients will not respond well to the vaccine. Only 315 patients participated in the trial and in order to completely confirm the claim, more patients should form part of trials. This international trial can perhaps be a starting point for further research and even help to one day develop a cure for HIV.