An Army virologist using diagnostic tools found traces of Ebola virus in patient samples in West Africa — a region thought to be untouched by the disease — seven years before the largest, deadliest Ebola outbreak took the world by surprise in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

The traces he found were antibodies, made by the body’s immune system and very specific to each invader, like Ebola virus, that enters the bloodstream, blood plasma, blood serum and other body fluids.

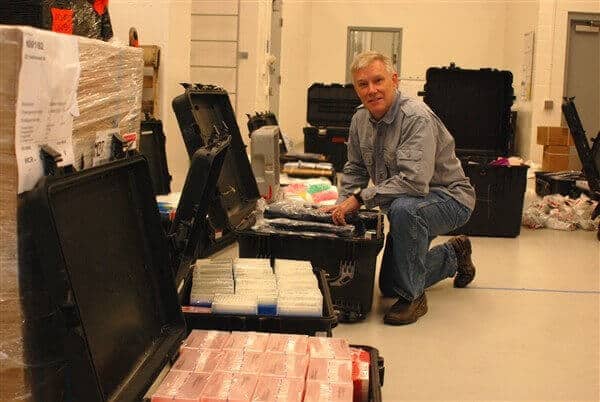

Dr. Randal J. Schoepp is chief of the Applied Diagnostics Department in the Diagnostic Systems Division at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, or USAMRIID, here.

He recently returned from Liberia and Sierra Leone, where he spent twelve weeks helping to set up an Ebola testing lab and training local personnel to run Ebola diagnostic tests on clinical samples. Schoepp is part of a USAMRIID team that has been in West Africa since March.

Building Host-country Capacity

“My interest has always been arthropod-borne diseases — in other words, mosquito-borne and tick-borne viruses, and hemorrhagic fever viruses,” Schoepp said during a recent DoD News interview at USAMRIID.

In 2006, Schoepp was working in Sierra Leone at the Kenema Government Hospital in Eastern Province, helping a collaboration of USAMRIID and Tulane University scientists who were there to develop and refine Lassa fever diagnostic tests and build host-country diagnostic capacity.

Lassa is a hemorrhagic fever illness that occurs in West Africa and is hyperendemic in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, meaning its incidence is high and continuing. The number of West African Lassa virus infections is 100,000 to 300,000 a year with about 5,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“One reason I was interested in Sierra Leone is because, for those of us who work with hemorrhagic fevers … this is the only place you can study them because you know they’re going to show up and you know where they’re going to be,” the virologist said.

At the Sierra Leone study site, Schoepp and his colleagues were testing their diagnostics and working to build diagnostic capacity for the country.

Detecting the Virus

The scientists were testing samples of blood plasma and blood serum using immunodiagnostics, or diagnostic tests that “use antibodies to detect the actual virus or virus products, or antibodies that result from infections with those viruses,” Schoepp explained.

On the other side of the diagnostics house, the virologist said, is testing by polymerase chain reaction technology to look for genomic material.

“PCR is exquisitely sensitive, very specific. That’s a really good thing when you know what’s there. When you don’t know what’s there it can be misleading, because if what’s in the area doesn’t match exactly, you’ll get a false negative,” he said.

“Immunodiagnostics are not nearly as sensitive as PCR, but they have a broad specificity, so you pick up all kinds of genetic variants and related viruses,” Schoepp said, adding that using both kinds of diagnostics at the same time is a perfect system “if you go into an area and you don’t know what’s going on.”

He added, “In this time of molecular, hurry up, fast, fast, fast, immunodiagnostics has fallen out of favor because it’s time consuming, laborious and the reagents are difficult to make. But they’re very useful, and in certain situations they’re vital.”

Diagnosing Lassa in Sierra Leone

As the work continued in Sierra Leone, the scientists found that, of the 500 to 700 samples a year submitted to the Kenema Government Hospital Lassa Diagnostic Lab from Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, only 30 percent to 40 percent were actually Lassa. Schoepp said he got interested in the 60 percent to 70 percent that weren’t Lassa.

The aim of his study, he explained, was to find out which other viruses caused serious illnesses in the region and to help medical and technical personnel there learn how to detect the illnesses.

The samples Schoepp looked at already had been screened for Lassa and malaria, and he and his colleagues ended up with about 400 samples, taken from 2006 to 2008, that represented 253 patients, he said.

In these samples he looked for other arthropod-borne viruses — “dengue, Rift Valley fever, West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, all the ones you would expect to see in Africa,” he said — as well as hemorrhagic fever viruses such as Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever, Marburg, Ebola and others.

Looking For Lassa, Finding Ebola

Out of all that, he said, the most significant finding “was that 8.6 percent of the samples had the earliest antibodies to Ebola,” called immunoglobulin M, or IgM, antibodies.

IgM is the first antibody to be made by the body to fight a new infection, Schoepp said, “so if you find IgM antibodies it tells you that you’re very close to the original infection.”

Looking further into the Ebola antibodies with the plaque reduction neutralization test, which many scientists consider the “gold standard” for detecting and measuring antibodies that can neutralize many disease-causing viruses, Schoepp saw that most of the Ebola antibodies were against the Zaire strain.

Ebola Zaire is the most virulent of the virus’s five strains, Schoepp said, and the one that is now causing the West African outbreak.

In a region supposedly untouched by Ebola except for a single case of the Tai Forest strain reported in Cote d’Ivoire in 1994, Schoepp said, this was big news that at the time could have been unwelcome in the three countries.

Medical Diplomacy

“I spent over a year going back to Sierra Leone, talking to the regional medical officers, talking to the ministry, making them understand that this is what we found,” in a careful process of medical diplomacy, Schoepp said.

Afterward, in August 2013, he submitted a scientific paper about the West African Ebola finding to CDC’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal. After nearly a year and reviews by two sets of scientists, the final reviewer told Schoepp, “I don’t believe there is Ebola virus in West Africa.”

A week later, Schoepp said, the West African Ebola outbreak was announced to the world and, after an email from Schoepp to the journal editor, “Undiagnosed Acute Viral Febrile Illnesses, Sierra Leone,” was published in July 2014.

“To me, it means that there is more Ebola out in the world than you would know by past outbreaks or by other evidence,” Schoepp said, discussing the paper’s results. “If you look for it, you have a very good chance of finding it.”

Diagnostics, he added, is the basis of everything.

“We set the stage for others to come in and do their therapeutics, their antivirals, their vaccines,” Schoepp said. “Knowing what’s there is one thing, and being able to do something about what’s there is another thing. So diagnostics gives the epidemiologists, immunologists and the therapeutic people something to do.”

In a time when globalization spreads diseases farther and faster than ever, Schoepp said, it’s a good time to be a virologist.

“Every time you think everything has happened, [severe acute respiratory syndrome] pops up or [Middle East respiratory syndrome-corona virus] pops up or Ebola pops up,” he said, adding that he often describes a virologist as being like a fireman.

“Somebody says ‘fire’ and a fireman runs toward it,” Schoepp said. “Somebody says ‘disease’ and a virologist runs toward it.”

Very informative article post.Really looking forward to read more. Really Cool.