A powerful class of antibiotics called carbapenems can circumvent antibiotic resistance thanks to a particular chain of atoms in their structure. Now, a team of researchers from Penn State and Johns Hopkins University have imaged an enzyme involved in the creation of this chain to better understand how it forms — and perhaps replicate the process to improve future antibiotics. A paper describing the process appears Feb. 2 in the journal Nature.

Carbapenems are naturally occurring potent, broad-spectrum antibiotics that belong to a larger group called beta-lactam antibiotics that also includes penicillin. Carbapenems are often used as a last resort to treat bacterial infections, including hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia — an increasing problem during the COVID-19 pandemic. Certain carbapenems have a side chain that includes two or three methyl groups — a carbon atom and three hydrogen atoms — that help them thwart antibiotic resistance.

“In many cases, bacteria can evolve resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics by degrading a structure in the antibiotic called the ‘beta-lactam ring,’ which renders it ineffective,” said Squire Booker, a biochemist at Penn State, investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and an author of the paper. “But the addition of the methyl groups in the side chain prevents this degradation, making carbapenems powerful clinical tools. In this study, we imaged a protein called TokK that we know facilitates the synthesis of the side chain in order to reconstruct the initial chemical steps in this process.”

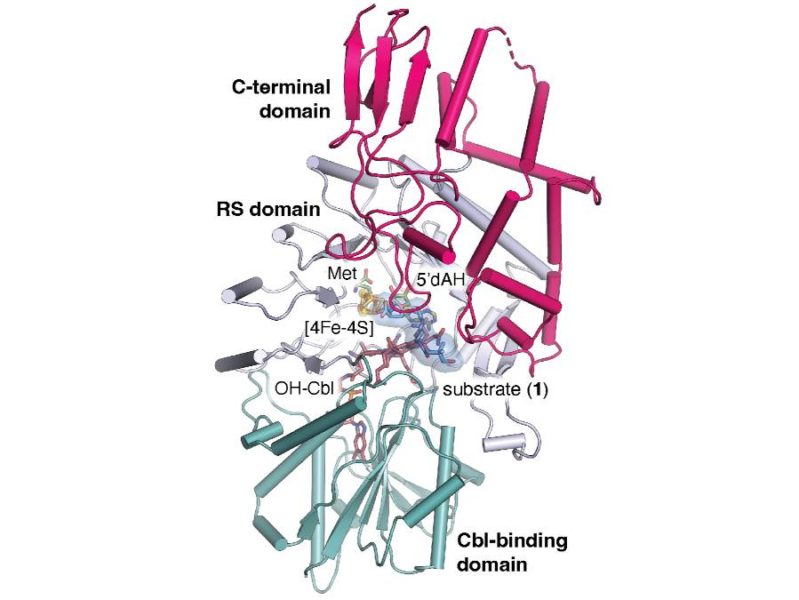

TokK is a type of radical SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) enzyme that is involved in the process of methylation — adding a methyl group. In this case, TokK helps facilitate the addition of three methyl groups to the antibiotic, building the side chain that is so critical in this antibiotic.

The researchers found that, like most radical SAM enzymes, TokK first uses one if its iron-sulfur clusters to convert a SAM molecule into a “free radical,” which propels the reaction forward. The radical then takes a hydrogen atom from the under-construction antibiotic. TokK then donates a methyl group from a part of its structure called methyl-cobalamin to the vacant spot on the antibiotic where the hydrogen was removed. This methylation process is repeated three times, ultimately producing the side chain with three methyl groups.

“TokK acts like a scaffold in this process, bringing together the methyl-cobalamin, a SAM molecule, and the antibiotic into an ideal position for transfer of the methyl group to occur,” said Hayley Knox, a graduate student at Penn State and an author of the paper. “The second methyl group is actually attached much more quickly than we would expect based on the energetics. We think that this is because the components are already so well aligned from the first step.”

Cobalamin, also known as vitamin B12, helps facilitate a variety of enzyme-driven reactions. However, this type of “radical chemistry” is uncommon in known reactions where cobalamin is involved, suggesting that cobalamin may play a different role than anticipated in many reactions.

“Typically, we think of methylcobalamin as being involved in what we call ‘polar chemistry’ rather than ‘radical chemistry,’” said Booker. “But here we found that TokK, and we think many other cobalamin-dependent radical SAM enzymes, use radical chemistry. It turns out that cobalamin is much more versatile than we had previously appreciated.”

This improved understanding of how the side chain in carbapenems is created could provide important insight for how to replicate this process and potentially improve antibiotics.

“Multiple methylations by a radical SAM enzyme are unusual, although not unprecedented, and have created a ‘library’ of two- and three-carbon variants of the carbapenem core in nature,” said Craig Townsend, Alsoph H. Corwin Professor of Chemistry at Johns Hopkins and an author of the paper. “Two methyl groups may be optimal for antibiotic activity, but one wonders if engineering of TokK to incorporate four or more of these groups could lead to further improvements in the running battle against bacterial resistance.”

Booker is an Evan Pugh University Professor of Chemistry and of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Holder of the Eberly Distinguished Family Chair in Science at Penn State. In addition to Booker, Knox, and Townsend, the research team includes Amie Boal, associate professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State, and Erica Sinner, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Penn State Eberly Family Distinguished Chair in Science, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.