Living organisms have adapted to the day-night cycle and, in most cases, evolved a “circadian clock” – that is: an actual cellular metronome – whose effects are not completely known yet.

A scientific team with members from EPFL and the Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences has found that in the case of the liver, the rhythm of protein production and release is dictated by both the organisms’ feeding behaviors and their internal clock.

Why is it that we don’t wake up in the middle of the night feeling hungry while it’s hard for us to endure eight hours without eating after breakfast? In our daily life, every one of us realizes that our body responds to the rhythm imposed by the succession of days and nights, which has important metabolic consequences. The jet lag syndrome is another manifestation of the interaction between our internal clock and the environmental cycles.

While many molecular studies have been conducted on living organisms’ circadian clocks, new analytical tools currently available allow a closer inspection of the real impact of this clock on some biological processes, in particular at a level of temporal protein abundance. This is exactly the research carried out in a joint study between EPFL and the Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences (NIHS), thanks to a grant from the Leenards Foundation disbursed in 2012. Their results have been published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the USA (PNAS).

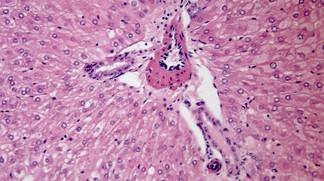

The researchers, under the direction of Frédéric Gachon (NIHS) and Felix Naef (EPFL), used mass spectrometry to analyze mice liver proteins. They measured the concentration of more than 5000 different proteins – whereas previous techniques only allowed to identify a few hundreds at best. “We have observed that 6% of the proteins are expressed in a rhythmic manner, explained Felix Naef. This rate seemed low to us, since we know that almost half of the active genes in the liver follow a rhythm in messenger RNA abundance. But the most amazing part was that more than half of these rhythmic proteins originate from genes whose messenger RNA is not influenced by the circadian clock.”

This apparent paradox suggests that the circadian clock does not only influence the production of proteins by the genes, but also the way the liver regulated the storage and release of proteins into the body.

The researchers observed an overnight accumulation of proteins, suggesting that their secretion is higher during the day. This results in a maximal plasma concentration during the night, the active period for mice. Unlike humans, mice are nocturnal animals, they eat and are active at night while resting during the day. “Our experiments seem to prove that the pace set by feeding patterns takes precedence over the circadian rhythm. However, it appears that the strongest effect takes place when these two rhythms overlap”, said Frédéric Gachon.

A next step in this research will attempt to translate some of these results to humans. “Our work will help develop strategies focused on diet to help treat patients suffering from disorders associated to circadian dysfunctions” said Felix Naef.

Adapted from a news release issued by Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne