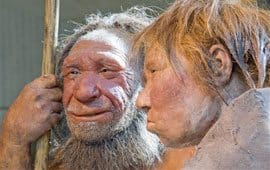

What happened to the Neanderthals? They left their African homes and migrated into Europe 350,000 to 600,000 years ago, well ahead of modern humans, who showed up only about 45,000 years ago. But within about 5,000 years of our arrival, the indigenous Neanderthals had disappeared.

Anthropologists have proposed that the Neanderthals may have been done in by terrible epidemics or an inability to adapt to climate changes of the era, but Stanford researchers now suggest culture wars of a sort might have spelled the end.

The team, led by biologist Marcus Feldman, came to their conclusion after creating mathematical models that demonstrated that it wasn’t necessary for the humans to outnumber the locals in order to prevail. A smaller band of humans with a more highly developed level of culture could eventually push out the Neanderthals, the models showed.

The edge wasn’t just raw intelligence. Archeological findings have shown that brain size was essentially the same for humans and Neanderthals, and recent paleo-anthropological studies suggest that Neanderthals were capable of a range of advanced intellectual behaviors typically associated with early modern humans.

But a more fully developed culture among humans could have led to being able to gather territory or hunt over a larger area, or a higher level of tool-making. And better tools probably meant better weapons.

“Presumably there was a lot of violence going on at that time,” said Feldman, who is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “I assume it wasn’t only constructive things done with tools. A hand axe can be used for constructive purposes and destructive purposes.”

Looking at the results of the modeling, the researchers concluded that a small population of humans with a high level of sophistication could have overwhelmed a larger, established population of Neanderthals that had been getting by with a lower level of cultural sophistication.

And the rich probably got richer in some sense, because a growing population of humans could support a higher level of cultural sophistication. The modeling also suggests then that it was not necessarily a genetic mutation that changed the human brain and provided a leg up for humans over Neanderthals, as has been suggested, Feldman said.

“They are presumably the last close relatives to us, before humans dominated the world,” he said.

Feldman’s research team included William Gilpin, a graduate student in applied physics at Stanford, and Kenichi Aoki of the Organization for the Strategic Coordination of Research and Intellectual Properties at Meiji University in Japan. He said that drawing from an interdisciplinary group of experts makes this type of work possible.

“One of the great things about Stanford is how easy this is to do,” he said. “It’s always been the case, since I did my doctorate over in the math department, that interdisciplinary research has been encouraged and strongly supported by the university.”

The research is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!