It’s an age-old quandary: Are we born “noble savages” whose best intentions are corrupted by civilization, as the 18th century Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau contended? Or are we fundamentally selfish brutes who need civilization to rein in our base impulses, as the 17th century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes argued?

After exploring the areas of the brain that fuel our empathetic impulses — and temporarily disabling other regions that oppose those impulses — two UCLA neuroscientists are coming down on the optimistic side of human nature.

“Our altruism may be more hard-wired than previously thought,” said Leonardo Christov-Moore, a postdoctoral fellow at UCLA’s Semel Institute of Neuroscience and Human Behavior.

The findings, reported in two recent studies, also point to a possible way to make people behave in less selfish and more altruistic ways, said senior author Marco Iacoboni, a UCLA psychiatry professor.

“This is potentially groundbreaking,” he said.

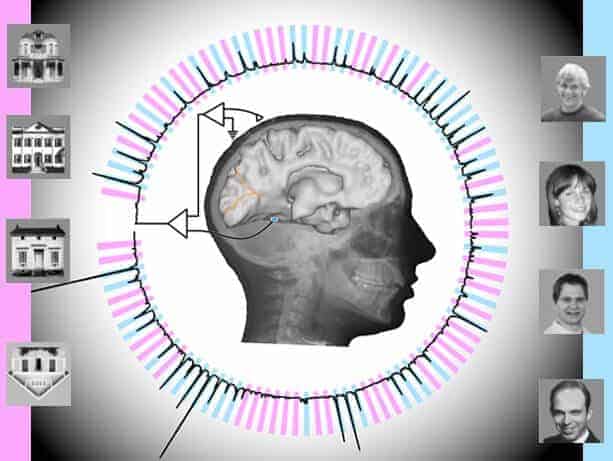

For the first study, which was published in February in Human Brain Mapping, 20 people were shown a video of a hand being poked with a pin and then asked to imitate photographs of faces displaying a range of emotions — happy, sad, angry and excited. Meanwhile, the researchers scanned participants’ brains with functional magnetic resonance imaging, paying close attention to activity in several areas of the brain.

One cluster they analyzed — the amygdala, somatosensory cortex and anterior insula — is associated with experiencing pain and emotion and with imitating others. Two other areas are in the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for regulating behavior and controlling impulses.

In a separate activity, participants played the dictator game, which economists and other social scientists often use to study decision-making. Participants are given a certain amount of money to either keep for themselves or share with a stranger. In the UCLA study, participants were given $10 per round for 24 rounds, and the recipients were actual Los Angeles residents whose names were changed for the game, but whose actual ages and income levels were used.

After each participant had completed the game, researchers compared their payouts with brain scans.

Participants with the most activity in the prefrontal cortex proved to be the stingiest, giving away an average of only $1 to $3 per round.

But the one-third of the participants who had the strongest responses in the areas of the brain associated with perceiving pain and emotion and imitating others were the most generous: On average, subjects in that group gave away approximately 75 percent of their bounty. Researchers referred to this tendency as “prosocial resonance” or mirroring impulse, and they believe the impulse to be a primary driving force behind altruism.

“It’s almost like these areas of the brain behave according to a neural Golden Rule,” Christov-Moore said. “The more we tend to vicariously experience the states of others, the more we appear to be inclined to treat them as we would ourselves.”

In the second study, published earlier this month in Social Neuroscience, the researchers set out to determine whether the same portions of the prefrontal cortex might be blocking the altruistic mirroring impulse.

In this study, 58 study participants were subjected to 40 seconds of a noninvasive procedure called theta-burst Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, which temporarily dampens activity in specific regions of the brain. In the 20 participants assigned to the control group, a portion of the brain that had to do with sight was weakened on the theory it would have no effect on generosity. But in the others, the researchers dampened either the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex or the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, which combine to block impulses of all varieties.

Christov-Moore said that if people really were inherently selfish, weakening those areas of the brain would free people to act more selfishly. In fact, though, study participants with disrupted activity in the brain’s impulse control center were 50 percent more generous than members of the control group.

“Knocking out these areas appears to free your ability to feel for others,” Christov-Moore said.

The researchers also found that who people chose to give their money to changed depending on which part of the prefrontal cortex was dampened. Participants whose dorsomedial prefrontal cortex was dampened, meanwhile, tended to be more generous overall. But those whose dorsolateral prefrontal cortex was dampened tended to be more generous to recipients with higher incomes — people who appeared to be less in need of a handout.

“Normally, participants would have been expected to give according to need, but with that area of the brain dampened, they temporarily lost the ability for social judgments to affect their behavior,” Christov-Moore said. “By dampening this area, we believe we laid bare how altruistic each study participant naturally was.”

The findings of both studies suggest potential avenues for increasing empathy, which is especially critical in treating people who have experienced desensitizing situations like prison or war.

“The study is important proof of principle that with a noninvasive procedure you can make people behave in a more prosocial way,” Iacoboni said.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!