The buildup of soft plaque in arteries that nourish the heart is more common and extensive in HIV-infected men than HIV-uninfected men, independent of established cardiovascular disease risk factors, according to a new study by National Institutes of Health grantees. The findings suggest that HIV-infected men are at greater risk for a heart attack than their HIV-uninfected peers, the researchers write in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In addition, blockage in a coronary artery was most common among HIV-infected men whose immune health had declined the most over the course of their infection and who had taken anti-HIV drugs the longest, the scientists found, placing these men at even higher risk for a heart attack.

“These findings from the largest study of its kind tell us that men with HIV infection are at increased risk for the development of coronary artery disease and should discuss with a care provider the potential need for cardiovascular risk factor screening and appropriate risk reduction strategies,” said Gary H. Gibbons, M.D., director of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of NIH.

“Thanks to effective treatments, many people with HIV infection are living into their 50s and well beyond and are dying of non-AIDS-related causes—frequently, heart disease,” said Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), also part of NIH. “Consequently, the prevention and treatment of non-infectious chronic diseases in people with HIV infection has become an increasingly important focus of our research.”

NIAID and NHLBI funded the study with additional support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, part of NIH.

Past studies of the association between heart disease and HIV infection have reached inconsistent conclusions. To help clarify whether an association exists, the current investigation drew participants from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), a study of HIV/AIDS in gay and bisexual men established by NIAID nearly 30 years ago.

“One advantage of the MACS is that it includes HIV-uninfected men who are similar to the HIV-infected men in the study in their sexual orientation, lifestyle, socioeconomic status and risk behavior, which makes for a good comparison group,” said Wendy S. Post, M.D., who led the study. Dr. Post is a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Another advantage was the MACS’ size, with nearly 7,000 men cumulatively enrolled, 1,001 of whom participated in the new study. The participants included 618 men who were HIV-infected and 383 who were not. All were 40 to 70 years of age, weighed less than 200 pounds, and had had no prior surgery to restore blood flow to the coronary arteries.

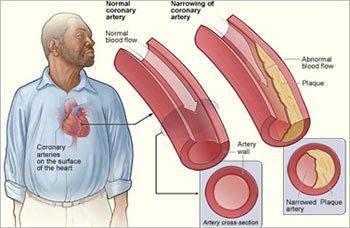

Dr. Post and colleagues investigated whether the prevalence and extent of plaque buildup in coronary arteries, a condition called coronary atherosclerosis, is greater in HIV-infected men than HIV-uninfected men and whether that plaque is soft or hard. Coronary atherosclerosis, especially soft plaque, is more likely to be a precursor of heart attack than hard plaque.

The scientists found coronary atherosclerosis due to soft plaque in 63 percent of the HIV-infected men and 53 percent of the HIV-uninfected men. After adjusting for cardiovascular disease risk factors, including high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol, high body mass index and smoking, the presence of soft plaque and the cumulative size of individual soft plaques were significantly greater in men with HIV infection.

In addition, by examining a subgroup of HIV-infected men, the scientists discovered two predictors of advanced atherosclerosis in this population. The first predictor deals with white blood cells called CD4+ T cells, which are the primary target of HIV and whose level, or count, is a measure of immune health. The researchers found that for every 100 cells per cubic millimeter decrease in a man’s lowest CD4+ T cell count, his risk of coronary artery blockage rose by 20 percent. The scientists also found that for every year a man had taken anti-HIV drugs, his risk of coronary artery blockage rose by 9 percent.

Because the investigators examined coronary artery plaque at a single point in time, further research is needed to determine whether coronary artery plaque in HIV-infected men is less likely to harden over time, or whether these men simply develop greater amounts of soft plaque, according to Dr. Post. In addition, she said, studies on therapies and behavioral changes to reduce risk for cardiovascular disease in men and women infected with HIV are needed to determine how best to prevent progression of atherosclerosis in this population.

The study was funded by NIH through grant numbers RO1-HL-095129, UL1-RR-025005, UO1-AI-35042, UL1-RR-025005, UM1-AI-35043, UO1-AI-35039, UO1-AI-35040, and UO1-AI-35041. The National Cancer Institute co-funds the MACS.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!