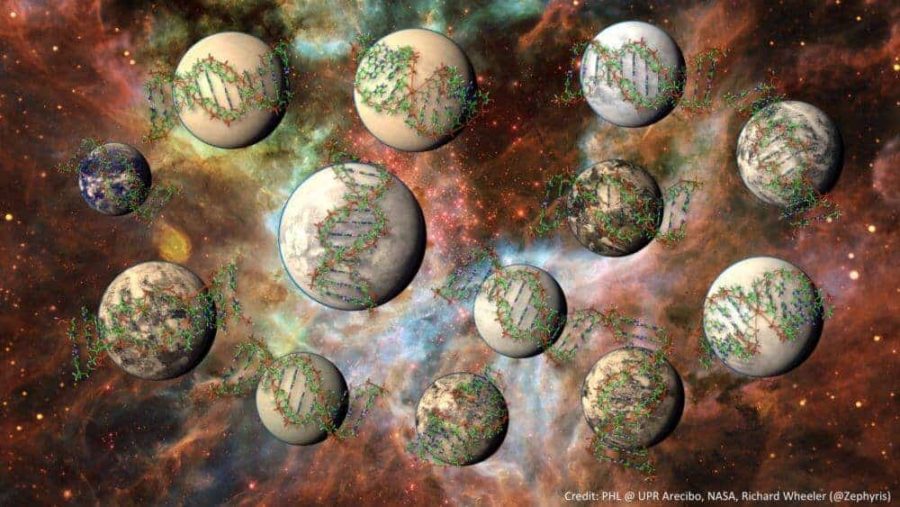

The number of planets in the Milky Way galaxy which could harbor complex life may be as high as 100 million, Washington State University astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch writes in a column posted this week on the Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine website.

The estimate, which assumes an average of one planet per star in the Milky Way, is drawn from a study believed to be the first quantitative assessment of the number of worlds in our galaxy that could harbor life above the microbial level.

Schulze-Makuch said the study is significant because it is the first to rely on observable data from actual planetary bodies beyond the solar system, rather than making educated guesses about the frequency of life on other worlds based on hypothetical assumptions.

The research was published recently in the journal Challenges by a group of scientists that includes Louis Irwin, of the University of Texas at El Paso; Alberto Fairen of Cornell University; Abel Mendez of the Planetary Habitability Laboratory at the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo; and Schulze-Makuch.

The researchers surveyed the growing list of more than 1,000 known planets outside the solar system. Using a formula that considers planetary density, temperature, substrate (liquid, solid or gas), chemistry, distance from its central star and age, they computed a “Biological Complexity Index (BCI),” which rates planets on a scale of 0 to 1.0 according to the number and degree of characteristics assumed to be important for supporting various forms of multicellular life.

“The BCI calculation revealed that 1 to 2 percent of exoplanets showed a BCI rating higher than Europa, a moon of Jupiter thought to have a subsurface global ocean which could harbor different forms of life,” writes Schulze-Makuch. “Based on an estimate of 10 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy, and assuming an average of one planet per star, this yields the figure of 100 million. Some scientists believe the number could be 10 times higher.”

He emphasizes that the study should not be taken as an indication that complex life actually exists on as many as 100 million planets, but rather that the figure is the best estimate to date of the number of planets in our galaxy likely to exhibit conditions supportive to such life.

“Also, it should be understood that complex life doesn’t mean intelligent life or even animal life, although it doesn’t rule either out,” Schulze-Makuch said. “It means simply that organisms larger and more complex than microbes could exist in a number of different forms, quite likely forming stable food webs like those found in ecosystems on Earth.

“Despite the large absolute number of planets that could harbor complex life, the Milky Way is so vast that, statistically, planets with high BCI values are very far apart,” Schulze-Makuch writes. “One of the closest and most promising extrasolar systems, known as Gliese 581, has possibly two planets with the apparent capacity to host complex biospheres, yet the distance from the Sun to Gliese 581 is about 20 light years.”

And most planets with a high BCI are much farther away, he said.

If the 100 million planets that the team says have the theoretical capacity for hosting complex life were randomly distributed across the galaxy, Schulze-Makuch said they would lie about 24 light years apart, assuming equal stellar density. And he estimates the distance between planets with intelligent life would likely be significantly farther.

“On the one hand it seems highly unlikely that we are alone,” he writes in the article. “On the other hand, we are likely so far away from life at our level of complexity, that a meeting with such alien forms might be improbable for the foreseeable future.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!