Water is thought to be embedded in the moon’s rocks or, if cold enough, “stuck” on their surfaces. It’s predominantly found at the poles. But scientists probably won’t find it intact on the sunlit side.

New research at the Georgia Institute of Technology indicates that ultraviolet photons emitted by the sun likely cause H2O molecules to either quickly desorb or break apart. The fragments of water may remain on the lunar surface, but the presence of useful amounts of water on the sunward side is not likely.

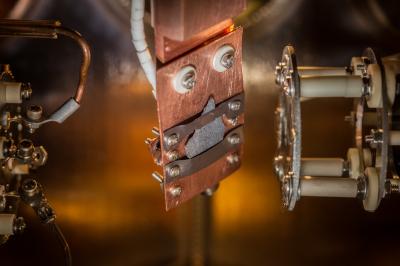

The Georgia Tech team built an ultra-high vacuum system that simulates conditions in space, then performed the first-ever reported measurement of the water photodesorption cross section from an actual lunar sample. The machine zapped a small piece of the moon with ultraviolet (157 nm) photons to create excited states and watched what happened to the water molecules. They either came off with a cross section of ∼ 6 x 10−19 cm2 or broke apart with a cross section of ∼ 5 x 10−19 cm2.. According to the team’s measurements, approximately one in every 1,000 molecules leave the lunar surface simply due to absorption of UV light.

Georgia Tech’s cross section values can now be used by scientists attempting to find water throughout the solar system and beyond.

“The cross section is an important number planetary scientists, astrochemists and the astrophysics community need for models regarding the fate of water on comets, moons, asteroids, other airless bodies and interstellar grains,” said Thomas Orlando, the Georgia Tech professor who led the study.

The number is relatively large, which establishes that solar UV photons are likely removing water from the moon’s surface. This research, which was carried out primarily by former Georgia Tech Ph.D. student Alice DeSimone, indicates the cross sections increase even more with decreasing water coverage. That’s why it’s not likely that water remains intact as H2O on the sunny side of the moon. Orlando compares it to sitting outside on a summer day.

“If a lot of sunlight is hitting me, the probability of me getting sunburned is pretty high,” said Orlando, a professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry and School of Physics. “It’s similar on the moon. There’s a fixed solar flux of energetic photons that hit the sunlit surface, and there’s a pretty good probability they remove water or damage the molecules.”

The result, according to Orlando, is the release of molecules such as H2O, H2 and OH as well as the atomic fragments H and O.

The research is published in two companion articles in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. The first discusses the water photodesorption. The second paper details the photodissociation of water and O(3PJ) formation on a lunar impact melt breccia.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!