Truman will be forgotten by three-fourths of college students by 2040

American presidents spend their time in office trying to carve out a prominent place in the nation’s collective memory, but most are destined to be forgotten within 50-to-100 years of their serving as president, suggests a study on presidential name recall released today by the journal Science.

“By the year 2060, Americans will probably remember as much about the 39th and 40th presidents, Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, as they now remember about our 13th president, Millard Fillmore,” predicts study co-author Henry L. Roediger III, PhD, a human memory expert at Washington University in St. Louis.

Roediger, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Arts & Sciences, has been testing the ability of undergraduate college students to remember the names of presidents since 1973, when he first administered the test to undergraduates while a psychology graduate student at Yale University.

His current study, co-authored with Washington University graduate student K. Andrew DeSoto, compares results from the presidential-recall tests Roediger has given to three generations of undergraduate college students (1974, 1991 and 2009) and a similar test offered online to 577 adults ages 18-69 in 2014.

While Roediger’s early research used the presidential-recall test to study patterns of remembering and forgetting in individual test takers, the new study was able to uncover how Americans forget presidents from our historical or popular memory over time.

In each test, participants were provided a numbered list with blank spaces and asked to fill in the names of all presidents they could remember in the order in which they served. If they could remember names but not the order, they were instructed to guess or to put the names off to the side. Thus, the results could be scored for recall of presidents with or without regard to correct order.

Findings showed several consistent patterns in how we have forgotten past presidents and offer a formula to predict the rate at which current presidents are likely to be forgotten by future generations.

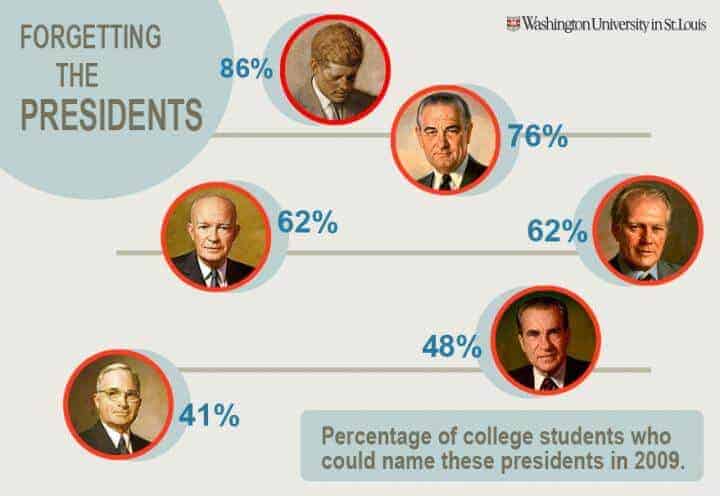

Among the six presidents who were serving or had served most recently when the test was first given in 1973, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson and Gerald R. Ford are now fading fast from historical memory, whereas John F. Kennedy has been better retained. The study estimates that Truman will be forgotten by three-fourths of college students by 2040, 87 years after his leaving office, bringing him down to the level of presidents such as Zachary Taylor and William McKinley.

The current data do not permit assessment of forgetting rates of the most recent presidents, and do not specify why some relatively recent presidents are forgotten more rapidly than others, Roediger said.

“Kennedy was president less than three years, but is today remembered much better than Lyndon Johnson,” Roediger said. “One idea is that his assassination made him memorable, but of course that does not apply to James Garfield or William McKinley, who were also assassinated and are remembered relatively poorly.

“Kennedy may be well recalled because his brothers and other family members were (and are) active in politics and help to keep his memory alive,” Roediger speculated.

HIllary Clinton, if elected in 2016, has the potential to be much better remembered than her husband, because her presidency would represent a unique first in American history. Barack Obama may be well remembered for the same reason, Roediger said.

The rate at which college students forgot the order of recent presidents remained remarkably consistent over time and across different groups of college students. In 1974, nearly all college students recalled Johnson and his ordinal position (36), but by 1991, the proportion remembering him dropped to 53 percent and by 2009, it plummeted to 20 percent.

When asked to name the presidents in the order they served, we as a nation do fairly well at naming the last few presidents, but our recall abilities then fall off quickly, with less than 20 percent able to remember more than the last eight or nine presidents in order, the study finds.

While Americans who were tested could name the nation’s first president (George Washington) and do reasonably well at naming the next three or four presidents in order, the recall success rate for early presidents also drops off sharply, with fewer than 25 percent of Americans able to recall more than the first five presidents in order.

“Out of the 150 college students we tested in 2009, only four of them were able to recall virtually every president and place each in the correct position,” DeSoto said. “It’s possible that these individuals used a mnemonic like a song or rhyme that they learned for the purpose of remembering the presidents.”

With a few interesting exceptions, the vast majority of presidents in the middle of pack — from No. 8, Martin Van Buren, to No. 30, Calvin Coolidge — already are largely forgotten by the average American, the study finds.

The probability that anyone who took the test could recall both the name and the order of most presidents in this middle range is quite low, and this level of poor recall for the middle presidents has generally held true in testing across all generations for nearly four decades.

A notable exception in this middle wasteland of presidential recall is Abraham Lincoln and his two immediate successors, Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant.

“Clearly, Lincoln and his successors are well remembered because of their association with the American Civil War and the ending of slavery, but it is notable that many students and adults also often know that Lincoln was the 16th president,” Roediger said.

Other pre-Coolidge presidents who were remembered reasonably well in the free recall portion of the test are Theodore Roosevelt (26), William Howard Taft (27) and Woodrow Wilson (28), a showing that could be related to their favorable rankings by historians and ongoing mentions in popular culture and news media, the researchers suggest.

Roediger’s prediction about the memorability of Reagan and other recent presidents hinges on two core principles of human memory that are confirmed by this study and related research.

First, when presented with information in a long list, we tend to best remember items that are presented at the beginning and end of the list. Second, items presented in the middle of a long list are better remembered when they are somehow distinctive and different from other items in the list.

America’s memory for Johnson and Reagan, like that for most presidents, is destined to fade along a quick and predictable trajectory as new elections inexorably push them and their memories further down the list of the most recent and currently best-remembered presidents, the study suggests.

While most collective memory research conducted thus far has explored how we as a nation remember historic events, such as the Holocaust or the 9/11 terror attacks, this study is among the first to focus on how we forget salient events of the past over generations and to obtain estimates of rate of forgetting over time.

“Our results show that memories of famous historical people and events can be studied objectively,” Roediger said. “The great stability in how these presidents are remembered across generations suggests that we as a nation share a seemingly permanent form of collective memory.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!