Galaxies can die early because the gas they need to make new stars is suddenly ejected, research published today suggests.

Most galaxies age slowly as they run out of raw materials needed for growth over billions of years. But a pilot study looking at galaxies that die young has found some might shoot out this gas early on, causing them to redden and kick the bucket prematurely.

Astrophysicist Ivy Wong, from the University of Western Australia node of the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), said there are two main types of galaxies; ‘blue’ galaxies that are still actively making new stars and ‘red’ galaxies that have stopped growing.

Most galaxies transition from blue to ‘red and dead’ slowly after two billion years or more, but some transition suddenly after less than a billion years–young in cosmic terms.

Dr Wong and her colleagues looked for the first time at four galaxies on the cusp of their star formation shutting down, each at a different stage in the transition.

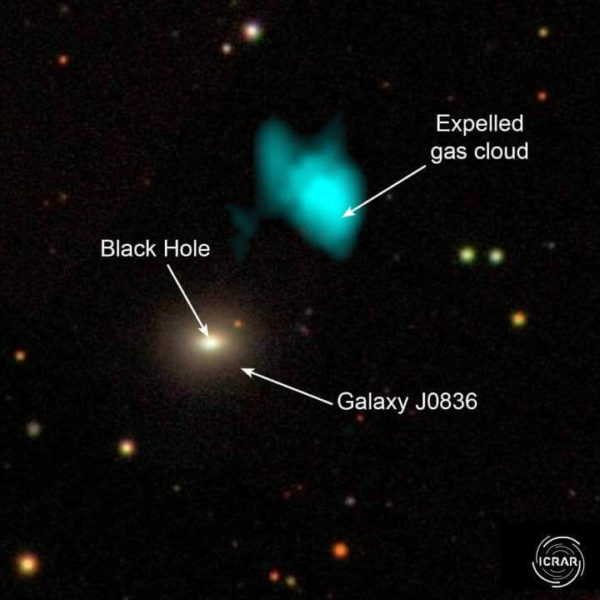

The researchers found that the galaxies approaching the end of their star formation phase had expelled most of their gas.

Dr Wong said it was initially hard to get time on telescopes to do the research because other astronomers did not believe the dying galaxies would have any gas left to see.

The exciting result means the scientists will be able to use powerful telescopes to conduct a larger survey and discover the cause of this sudden shutdown in star formation.

Dr Wong said it is unclear why the gas was being expelled. “One possibility is that it could be blown out by the galaxy’s supermassive black hole,” she said.

“Another possibility is that the gas could be ripped out by a neighbouring galaxy, although the galaxies in the pilot project are all isolated and don’t appear to have others nearby.”

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Professor Kevin Schawinski said the researchers predicted that the galaxies had to rapidly lose their gas to explain their fast deaths.

“We selected four galaxies right at the time where this gas ejection should be occurring,” he said. “It was amazing to see that this is exactly what happens!” The study appeared in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, published by Oxford University Press.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!