Scientists have long known that our ability to think quickly and recall information, also known as fluid intelligence, peaks around age 20 and then begins a slow decline. However, more recent findings, including a new study from neuroscientists at MIT and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), suggest that the real picture is much more complex.

The study, which appears in the journal Psychological Science, finds that different components of fluid intelligence peak at different ages, some as late as age 40.

“At any given age, you’re getting better at some things, you’re getting worse at some other things, and you’re at a plateau at some other things. There’s probably not one age at which you’re peak on most things, much less all of them,” says Joshua Hartshorne, a postdoc in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and one of the paper’s authors.

“It paints a different picture of the way we change over the lifespan than psychology and neuroscience have traditionally painted,” adds Laura Germine, a postdoc in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental genetics at MGH and the paper’s other author.

Measuring peaks

Until now, it has been difficult to study how cognitive skills change over time because of the challenge of getting large numbers of people older than college students and younger than 65 to come to a psychology laboratory to participate in experiments. Hartshorne and Germine were able to take a broader look at aging and cognition because they have been running large-scale experiments on the Internet, where people of any age can become research subjects.

Their web sites, gameswithwords.org and testmybrain.org, feature cognitive tests designed to be completed in just a few minutes. Through these sites, the researchers have accumulated data from nearly 3 million people in the past several years.

In 2011, Germine published a study showing that the ability to recognize faces improves until the early 30s before gradually starting to decline. This finding did not fit into the theory that fluid intelligence peaks in late adolescence. Around the same time, Hartshorne found that subjects’ performance on a visual short-term memory task also peaked in the early 30s.

Intrigued by these results, the researchers, then graduate students at Harvard University, decided that they needed to explore a different source of data, in case some aspect of collecting data on the Internet was skewing the results. They dug out sets of data, collected decades ago, on adult performance at different ages on the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale, which is used to measure IQ, and the Weschler Memory Scale. Together, these tests measure about 30 different subsets of intelligence, such as digit memorization, visual search, and assembling puzzles.

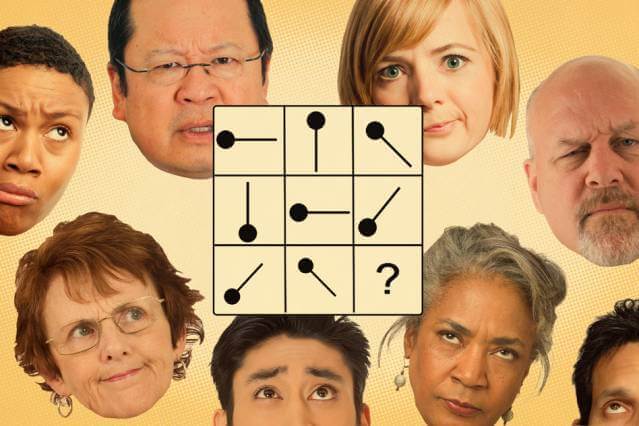

Hartshorne and Germine developed a new way to analyze the data that allowed them to compare the age peaks for each task. “We were mapping when these cognitive abilities were peaking, and we saw there was no single peak for all abilities. The peaks were all over the place,” Hartshorne says. “This was the smoking gun.”

However, the dataset was not as large as the researchers would have liked, so they decided to test several of the same cognitive skills with their larger pools of Internet study participants. For the Internet study, the researchers chose four tasks that peaked at different ages, based on the data from the Weschler tests. They also included a test of the ability to perceive others’ emotional state, which is not measured by the Weschler tests.

The researchers gathered data from nearly 50,000 subjects and found a very clear picture showing that each cognitive skill they were testing peaked at a different age. For example, raw speed in processing information appears to peak around age 18 or 19, then immediately starts to decline. Meanwhile, short-term memory continues to improve until around age 25, when it levels off and then begins to drop around age 35.

For the ability to evaluate other people’s emotional states, the peak occurred much later, in the 40s or 50s.

Christopher Chabris, an associate professor of psychology at Union College, said a key feature of the study’s success was the researchers’ ability to gather and analyze so much data, which is unusual in cognitive psychology.

“You need to look at a lot of people to discover these patterns,” says Chabris, who was not part of the research team. “They’re taking the next step and showing a more fine-grained picture of how cognitive abilities differ from one another and the way they change over time.”

More work will be needed to reveal why each of these skills peaks at different times, the researchers say. However, previous studies have hinted that genetic changes or changes in brain structure may play a role.

“If you go into the data on gene expression or brain structure at different ages, you see these lifespan patterns that we don’t know what to make of. The brain seems to continue to change in dynamic ways through early adulthood and middle age,” Germine says. “The question is: What does it mean? How does it map onto the way you function in the world, or the way you think, or the way you change as you age?”

Accumulated intelligence

The researchers also included a vocabulary test, which serves as a measure of what is known as crystallized intelligence — the accumulation of facts and knowledge. These results confirmed that crystallized intelligence peaks later in life, as previously believed, but the researchers also found something unexpected: While data from the Weschler IQ tests suggested that vocabulary peaks in the late 40s, the new data showed a later peak, in the late 60s or early 70s.

The researchers believe this may be a result of better education, more people having jobs that require a lot of reading, and more opportunities for intellectual stimulation for older people.

Hartshorne and Germine are now gathering more data from their websites and have added new cognitive tasks designed to evaluate social and emotional intelligence, language skills, and executive function. They are also working on making their data public so that other researchers can access it and perform other types of studies and analyses.

“We took the existing theories that were out there and showed that they’re all wrong. The question now is: What is the right one? To get to that answer, we’re going to need to run a lot more studies and collect a lot more data,” Hartshorne says.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!