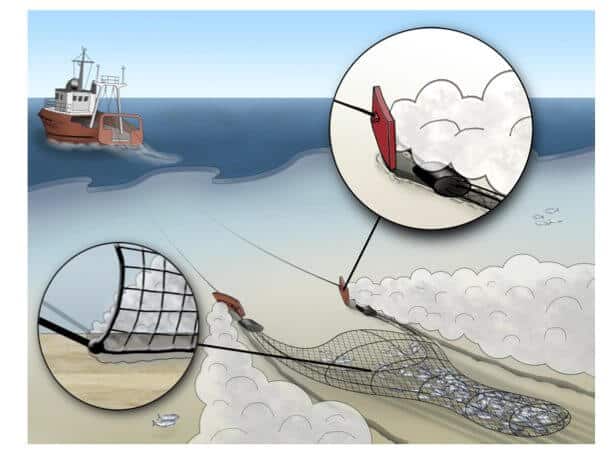

Recent scientific work outlines the severe consequences the practice of bottom trawling has on loose sediment on the ocean floor. Bottom trawling is a widespread industrial fishing practice that involves dragging heavy nets, large metal doors and chains over the seafloor to catch fish. Although previous studies documented the direct impacts of bottom trawling on corals, sponges, fishes and other animals, an understanding of the global impact of this practice on the seabed remained unclear until now. The first calculation of how much of the seabed is resuspended (or stirred up) by bottom-trawling shows that the sediment mass is approximately the same amount of all sediment being deposited on the world’s continental shelves by rivers each year (almost 22 gigatons).

Understanding regional and global magnitudes of resuspended sediment is an essential baseline for the analysis of the environmental consequences for continental shelf habitats and their associated seafloor and open-ocean ecosystems. The scientists found new ways to look at and into the seabed to document the evidence of the effects of bottom trawling.

Bottom trawling can result in vastly different effects on different types of seabed sediment (such as sand, silt or mud), each with different ecological consequences. Trawling destroys the natural seafloor habitat by essentially rototilling the seabed. All of the bottom-dwelling plants and animals are affected, if not outright destroyed by tearing up root systems or animal burrows. By resuspending bottom sediment, nutrient levels in the ambient water, and the entire chemistry of the water is changed. Resuspended sediment can lower light levels in the water, and reduce photosynthesis in ocean-dwelling plants, the bottom of the food web. The resuspended sediment is carried elsewhere by currents, and often lost from the local ecosystem. It maybe deposited elsewhere along the continental shelf, or in many cases, permanently lost from the shelf to deeper waters. Changing parts of the seafloor from soft mud to bare rock can eliminate those creatures that live in the sediment. Species diversity and habitat complexity are directly affected by changing the physical environment of sand, mud or rock that results from trawling.

“This study raises serious concerns about the future stability of continental shelves – the very source of the vast majority of the fish we consume,” said geological oceanographer and lead author Ferdinand Oberle, now a visiting scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey, and previously with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and MARUM, the Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen (Germany) when the study was done. “A farmer would never plow his land again and again during a rainstorm, watching all his topsoil be washed away, but that is exactly what we are doing on continental shelves on a global scale.”

As part of the study, scientists developed a new, universal approach to calculate bottom-trawling-induced sediment resuspension that gives marine management a new and important tool to assess the impact from bottom trawling. Previous studies characterized the seabed as either “trawled” or “untrawled” but with these novel methodologies it was possible to show systematically a range of bottom-trawling-induced changes to the seabed and classify them in accordance with how often the seabed was disturbed by bottom trawlers.

“The global calculations were a big surprise and we calculated them at least 10 times to make sure we were not making a mistake. I am still in awe of these results and their environmental implications,” said USGS oceanographer Curt Storlazzi, a coauthor of the paper who helped develop the computational models for the study.

These new understandings about the effects of bottom trawling, come out of scientific cruises on the Research Vessel METEOR from Germany to the offshore area northwest of the Iberian peninsula with a team of international scientists. During the cruises, scientists conducted sidescan-sonar surveys and collected bottom current data. Laser sediment particle samplers and a remotely-operated submersible vessel were utilized as well. After the cruises, laboratory work involving lead-isotope dating and sediment grain-size analysis, and the development of a sediment mobilization model contributed to the conclusions of the study.

Two new research papers to come out of this study were published in Elsevier’s “Journal of Marine Systems,” and are available online:

“What a drag: Quantifying the global impact of chronic bottom trawling on continental shelf sediment”

“Deciphering the lithological consequences of bottom trawling to sedimentary habitats on the shelf”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!