Research published in the journal Nature on May 19, 2016 has revealed that vast regions of the Totten Glacier in East Antarctica are fundamentally unstable and have contributed significantly to rising sea levels several times in the past.

Totten Glacier is the most rapidly thinning glacier in East Antarctica, and this study raises concerns that a repeat scenario could be underway as the climate warms.

An international consortium led by The University of Texas at Austin’s Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), a unit at the university’s Jackson School of Geosciences, led the research and data collection for the study. Alan Aitken of the University of Western Australia’s School of Earth and Environment was lead author.

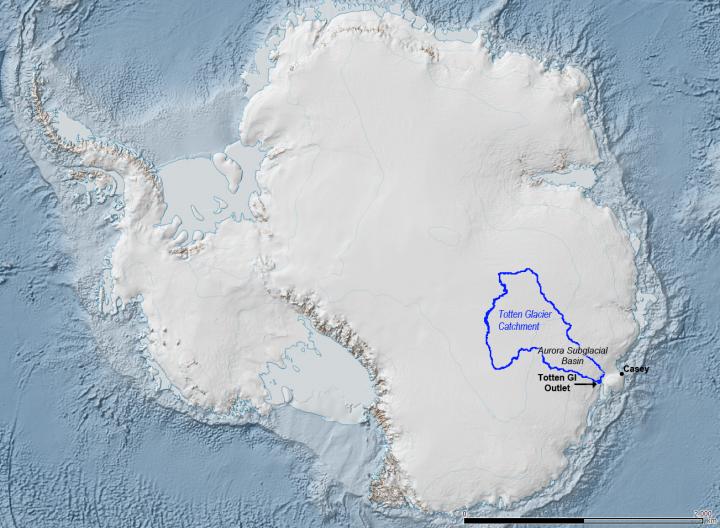

Totten Glacier is East Antarctica’s largest outlet of ice and a key region for understanding the large-scale and long-term vulnerabilities of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Until now, knowledge of the region’s glacial history has been very limited. While other studies have indicated that this region of the ice sheet may have retreated in the past, this study reveals direct linkages between the modern Totten Glacier and the eroded landscape currently buried in ice hundreds of kilometers inland.

“We now know how the ice sheet evolves over the landscape in East Antarctica and where it is susceptible to rapid retreat, which gives us insight into what is likely to happen in the years ahead,” said ICECAP lead Principal Investigator Donald D. Blankenship, Senior Research Scientist at UTIG.

Totten Glacier’s catchment is a collection basin for ice and snow that flows through the glacier.

“Totten Glacier’s catchment is covered by nearly two-and-a-half miles of ice, filling a California-sized sub-ice basin that reaches depths of over one mile below sea level,” Blankenship said. “This study shows that this system could have a large impact on sea level in a short period of time.”

The UTIG-led ICECAP (International Collaboration for Exploration of the Cryosphere through Aerogeophysical Profiling) project collected the data over five Antarctic field campaigns using an aircraft equipped with instruments to assess the ice and measure the shape of the landscape and rocks beneath it. The airplane was outfitted with radar that can measure ice several miles thick, lasers to measure the shape and elevation of the ice surface, and equipment that senses the Earth’s gravity and magnetic field strengths, which are used to infer the sub-ice geology.

The study used ice-penetrating radar, magnetic and gravity data to determine the thickness of the ice-sheet and the sediment thickness under the ice sheet. These were used to map glacial erosion beneath the ice and find two unstable zones where the ice sheet is prone to rapid collapse.

“By examining the characteristic patterns of erosion left by past ice sheet advance and retreat, revealed through mapping the topographic surface and the thickness of sedimentary rocks beneath, this paper demonstrates direct evidence of past changes in the ice sheet in the Totten region,” Aitken said.

The study found the transition between the stable and unstable states has occurred repeatedly during the life of the ice sheet.

“If this was to happen again, with a warmer climate than today, it could lead to a rapid rise in sea level of over a meter,” Aitken said.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!