There are those who spread disease, and then there are the “super spreaders.”

So says a new study by researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, who examined how a devastating infectious disease is passed among an amphibian population. The research, published this week in Biology Letters, may also lend new insights into how humans spread such ailments as well, said Robin Warne, assistant professor of zoology at SIU’s Center for Ecology.

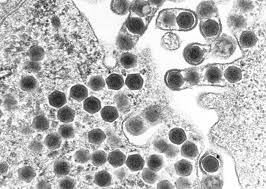

The researchers were working with ranavirus, which scientists suspect is playing a role in the global decline of amphibian species.

Most viruses are very specific to the animals they impact. It’s very difficult and unusual for a single virus to wreak havoc in several species. Not so the ranavirus. This killer hits several species of vertebrates, including fish, amphibians and reptiles. Unleashed in a local pond, the ranavirus routinely wipes out every tadpole living in it.

Two of Warne’s students, Alessandra Araujo, a zoology master’s student, and Lucas Kirschman, a doctoral student, found that certain “personality” types in tadpoles are better at spreading the disease through a combination of their behavior and their physical susceptibility to the ranavirus.

“Some individuals, often termed ‘super-spreaders,’ are much more effective at transmitting infections and thus can disproportionally contribute to the risk of disease outbreaks,” Warne said. “Super-spreaders are expected to have traits that include greater susceptibility to infection, and greater infectiousness, which is to say they are more likely to infect their peers during interactions.”

The research provides insight into individual traits that contribute to rapid and often devastating infectious disease spread among animals and humans alike, Warne said. And it’s largely related to how aggressively the tadpoles behave at feeding time.

In laboratory experiments, the researchers found that some tadpoles sit on the bottom near where food often is available, while others tend to swim almost nervously about. The ones that sit on the bottom, it turns out, are more aggressive when it comes to foraging for food. The same tadpoles have a higher metabolic rate and a lower amount of stress hormones than the ones that swim about.

Using a small population of 160 wood frog larvae, Warne and his students assigned each a “boldness rating” and then infected one of them with a lethal dose of the ranavirus virus. They then studied how likely they were to spread the disease when they were sick, but still healthy enough to interact with their environment. Because the water filter in each tank contained an ultraviolet light that killed any free-floating virus, disease could only be transmitted directly from one larva to another

“We found that bolder larvae — those who moved faster toward food sources and spent less time swimming alone in the water — caused more infections than their more passive peers,” Warne said. “Bolder animals were also more likely to become infected, probably due to their increased interactions with infected peers.

“Because larval amphibians, like other animals and humans, have stereotypical behavioral personalities, these results suggest that such traits could be valuable in the identification of super-spreaders and contribute to our capacity to understand and potentially managing disease outbreaks,” he said.

Warne said the research project was inspired by a senior research thesis conducted by Tom Egdorf, who earned his degree in zoology at SIU in 2013. A faculty seed grant from the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research to Warne supported Egdorf’s work.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!