A Washington State University researcher has found a mechanism that strongly influences whether or not an animal is likely to drink a lot of alcohol.

“It takes them from drinking the equivalent of three to four units of alcohol in one to two hours, down to one to two units,” said David Rossi, a WSU assistant professor of neuroscience.

Writing in the latest Journal of Neuroscience, Rossi and colleagues at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) and the U.S. Veterans Administration (VA) Portland Health Care System said the mechanism offers a new target for drug therapies that can curb excessive drinking. It may be particularly effective among problem drinkers, half of whom are believed to have a genetically determined tendency to abuse alcohol.

Alcohol triggers receptors that suppress brain circuits

The mechanism is found in the cerebellum, a part of the brain at the back of vertebrate skulls, in small neurons called granule cells. Sitting on the cells are proteins called GABAA receptors (pronounced “GABA A”) that act like traffic cops for electrical signals in the nervous system.

When activated, the GABAA receptors suppress the firing of neurons, or brain circuits. Benzodiazepines, which enhance GABAA signaling, reduce this excitability, which is why they are used to treat epilepsy.

Alcohol can also enhance GABAA receptor signaling and reduce firing in the brain, which is why it reduces anxiety and social inhibitions. In the cerebellum, it can lead to swaying, stumbling and slurred speech.

“You’re inhibiting the circuit that executes normal motor function,” said Rossi.

Genetic link to receptor response

But alcohol does not act the same on every brain. In 2013, shortly before Rossi came to WSU from OHSU, he and his colleagues there linked the genes that influence ethanol consumption and the response of granule cell GABAA receptors to ethanol.

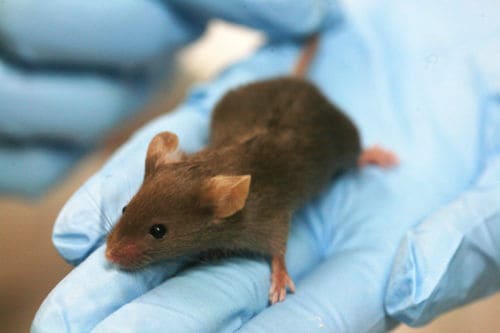

Much of their story is a tale of two specially bred mice.

The D2 mouse is a cheap drunk. After the equivalent of one or two drinks, it has trouble staying on a rotating cylinder.

“He won’t drink much,” said Rossi. “At most he’ll have one or two drinks.”

The B6 mouse, however, will stay on a rotating cylinder even after drinking three times as much alcohol, “which is beyond the drunk driving limit,” said Rossi.

What’s more, the D2 mouse is a teetotaler. After those first drinks, it stops. Under the right circumstances, the B6 mouse will binge.

“It mirrors the human situation,” said Rossi. “If you’re sensitive to the motor-impairing effects of alcohol, you don’t tend to drink much. If you’re not sensitive, you drink more.”

Drug counteracts genetic predilection to alcohol

In their earlier work, which was published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, Rossi and his colleagues saw clear differences in the way the cerebellar granule cell GABAA receptors reacted to alcohol in the two breeds of mice.

In contrast to the D2 mouse, the cerebellar GABAA receptors in the B6 mouse were suppressed by alcohol. Rossi called this “an obvious neural signature to a behavioral predilection to alcohol.”

For the recent paper, Rossi and his colleagues injected a drug called THIP into the cerebellum of B6 mice. THIP activates the GABAA receptor, recreating the effect that alcohol has on low drinking D2 mice. It ended up deterring the B6 mice from drinking.

The finding, said Rossi, highlights a new region and new targets that can be manipulated “to deter excessive alcohol consumption, and potentially with fewer side effects than other existing targets and brain circuits.”

Funding for the study, the bulk of which was performed at OHSU, came from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the American Heart Association and the VA Portland Health Care System.

The work is in keeping with WSU’s Grand Challenges, a suite of research initiatives aimed at large societal issues. It is particularly relevant to the challenge of sustaining health and its themes of healthy communities and individual health and wellness.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!