Two papers published by an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside and several collaborators explain why the universe has enough energy to become transparent.

The study led by Naveen Reddy, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at UC Riverside, marks the first quantitative study of how the gas content within galaxies scales with the amount of interstellar dust.

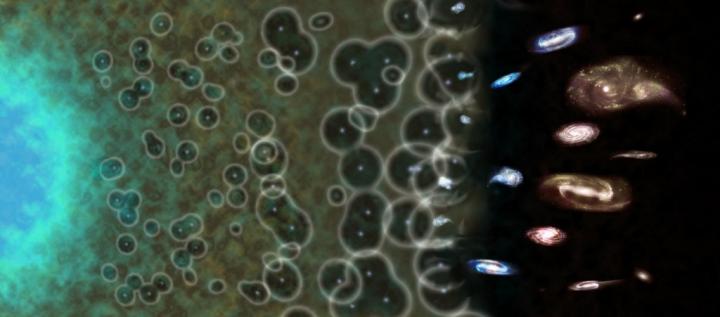

This analysis shows that the gas in galaxies is like a “picket fence,” where some parts of the galaxy have little gas and are directly visible, whereas other parts have lots of gas and are effectively opaque to ionizing radiation. The findings were just published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The ionization of hydrogen is important because of its effects on how galaxies grow and evolve. A particular area of interest is assessing the contribution of different astrophysical sources, such as stars or black holes, to the budget of ionizing radiation.

Most studies suggest that faint galaxies are responsible for providing enough radiation to ionize the gas in the early history of the universe. Moreover, there is anecdotal evidence that the amount of ionizing radiation that is able to escape from galaxies depends on the amount of hydrogen within the galaxies themselves.

The research team led by Reddy developed a model that can be used to predict the amount of escaping ionizing radiation from galaxies based on straightforward measurements on how “red,” or dusty, their spectra appear to be.

Alternatively, with direct measurements of the ionizing escape fraction, their model may be used to constrain the intrinsic production rate of ionizing photons at around two billion years after the Big Bang.

These practical applications of the model will be central to the interpretation of escaping radiation during the cosmic “dark ages,” a topic that is bound to flourish with the coming of 30-meter telescopes, which will allow for research unfeasible today, and the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA’s next orbiting observatory and the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The research ties back to some 400,000 years after the Big Bang, when the universe entered the cosmic “dark ages,” where galaxies and stars had yet to form amongst the dark matter, hydrogen and helium.

A few hundred million years later, the universe entered the “Epoch of Reionization,” where the gravitational effects of dark matter helped hydrogen and helium coalesce into stars and galaxies. A great amount of ultraviolet radiation (photons) was released, stripping electrons from surrounding neutral environments, a process known as “cosmic reionization.”

Reionization, which marks the point at which the hydrogen in the Universe became ionized, has become a major area of current research in astrophysics. Ionization made the Universe transparent to these photons, allowing the release of light from sources to travel mostly freely through the cosmos.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!