Instead of building a better mouse trap, Georgia Institute of Technology researchers have built a better mouse cage. They’ve created a system called EnerCage (Energized Cage) for scientific experiments on awake, freely behaving small animals. It wirelessly powers electronic devices and sensors traditionally used during rodent research experiments, but without the use of interconnect wires or bulky batteries. Their goal is to create as natural an environment within the cage as possible for mice and rats in order for scientists to obtain consistent and reliable results. The EnerCage system also uses Microsoft’s Kinect video game technology to track the animals and recognize their activities, automating a process that typically requires researchers to stand and directly observe the rodents or watch countless hours of recorded footage to determine how they react to experiments.

The wirelessly energized cage system was presented this month at the International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) in Orlando, Florida.

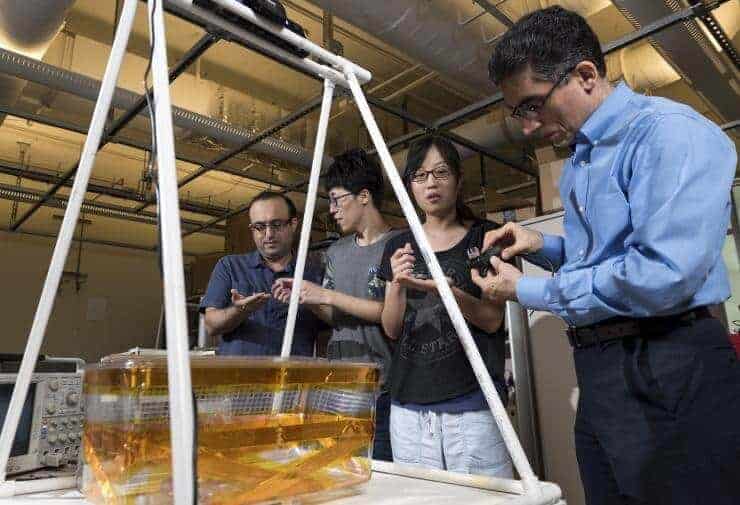

The Georgia Tech EnerCage is wrapped with carefully oriented strips of copper foils that can inductively power the cage and the electronics implanted in, or attached to, one or more animal subjects inside the cage. The system can run indefinitely and collect data without human intervention because of wireless communication and power transmission.

“It’s always better to keep an animal in its natural settings with minimum burden or stress to improve the quality of an experiment,” said Maysam Ghovanloo, an associate professor in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, who developed the EnerCage. “Anything that is abnormal or unnatural may bias the experiment, no matter what experiment in any field. That includes grabbing the animal to attach or detach wires, change batteries or transferring it from one cage to another.”

Ghovanloo uses four resonating copper coils to create a homogenous magnetic field inside the cage. The built-in closed loop power control mechanism supplies enough power to compensate for all freely behaving animal subject activities, whether they’re standing up, crouching down, or walking around the cage. The small headstage for the animal is also wrapped with resonators to deliver power to a receiver coil.

The Kinect is suspended about three feet above the cage. It has a high-definition camera, an infrared depth camera, and four microphones to record and analyze the animal behavior. It can capture both a two-dimensional high-resolution image of a rat’s location and a three-dimensional image that would identify its body posture.

“We’re building computer algorithms to determine if the animal is standing, sitting, sleeping, grooming, eating, drinking or doing nothing,” said Ghovanloo. “We’re hoping to reduce the expensive costs of new drug and medical device development by allowing machines to do mundane, repetitive tasks now assigned to humans.”

The Georgia Tech team is working in partnership with Emory University, hoping to impact the clinical efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS). A growing number of clinical trials are using DBS to treat disorders of the central nervous system, such as Parkinson’s disease, depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. The cellular mechanisms that contribute to the clinical efficacy of DBS remain largely unknown, however.

Emory’s Donald (Tig) Rainnie and his research team use freely moving rodent models to examine the effects of DBS on neural circuits thought to be disrupted in depression. They have tested the EnerCage system.

“The requirement to use a tethered headstage to record neural data and apply the DBS has hindered progress in this field,” said Rainnie, a researcher at Emory’s Yerkes National Primate Research Center and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science. “We provided critical feedback, via beta testing of the EnerCage system, on how to maximize the utility of the system for different behavioral applications. We found a key advantage of the EnerCage system is that it will allow researchers to conduct chronic DBS and track associated behavioral changes for days, if not weeks, without disturbing the test animals.”

Until now, Rainnie says, that hasn’t been possible, and it is key to understanding the long-term benefits of DBS in patients.

The next steps at Georgia Tech are designing EnerCage-compatible implants, such as one for delivering drugs, and expanding the system to a network of dozens of cages that can collect data from multiple animals at the same time.

The conference paper, “A Wirelessly Powered Homecage with Animal Behavior Analysis and Closed-Loop Power Control,” is co-authored by Yaoyao Jia, Zheyuan Wang, Daniel Canales, Morgan Tinkler, Chia-Chun Hsu, Teresa E. Madsen and S. Abdollah Mirbozorgi.

The work is supported in part by the National Science Foundation (ECCS-1407880 and ECCS-1408318) and the National Institute of Health’s National Institute of Biomedical Imaging Bioengineering (1R21EB018561). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!