Some genetic diseases persist for generation after generation because the genes that cause them can benefit human health.

Sickle cell anemia is one example: This disorder compels red blood cells to take on a crescent moon shape, leading to anemia. But carrying a copy of the sickle cell gene can guard against malaria.

Not all ancient diseases come with such a blessing, however.

A new study probes the evolutionary history of eczema, and finds no evidence that a genetic predisposition for this disorder has helped humans.

The research — published on Sept. 27 in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution — examines a genetic variant strongly associated with the most common form of eczema, atopic dermatitis.

This skin condition can cause a slew of unpleasant symptoms, including extreme itchiness and dry, scaly rashes, but there doesn’t seem to be a tradeoff for this discomfort: The genetic variant studied appears to be a random vestige of evolution, says University at Buffalo biologist Omer Gokcumen, who led the research.

“We present a complex evolutionary history of this disease variant, and it seems to be just bad luck that it has endured for so long,” says Gokcumen, PhD, an assistant professor of biological sciences in the UB College of Arts and Sciences. “Unlike other disease variants, such as those linked to sickle cell anemia or psoriasis, the one we studied is just not that important from the standpoint of evolution. It doesn’t appear to affect what biologists call ‘fitness,’ which is another word for reproductive success.”

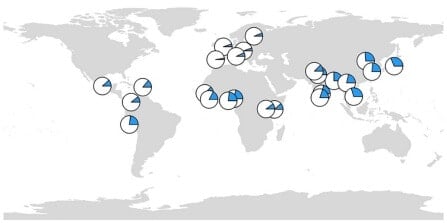

The research was based on a data set that included the genomes of more than 2,500 people around the world.

The roots of susceptibility to eczema

The gene at the heart of the research is the filaggrin gene, which tells the body how to make a protein of the same name in skin cells.

In some people, inherited genetic mutations cause the filaggrin gene to stop working, impairing healthy skin function and creating an increased risk for developing eczema.

The study found that “loss of function” mutations are significantly more common in filaggrin than in other human genes. However, despite this prevalence, the variants don’t appear to serve an adaptive purpose: “The loss of function creates a susceptibility to eczema, but it does not appear to have an effect on the reproductive success of modern humans,” Gokcumen says.

A hitchhiking mutation

The scientists’ conclusions held true even when they took a closer look at the genomes of individuals from East Asia, who are more likely to have broken filaggrin genes than people from other parts of the world.

A genomic analysis showed that this trend may have been an artifact of evolutionary hitchhiking: In East Asia, many people share a genetic profile that includes a loss-of-function mutation for filaggrin, paired with a notable mutation in a nearby gene that carries instructions for making hornerin, another human protein.

While the filaggrin mutation did not appear to have importance from the standpoint of evolution and adaptation, the hornerin mutation did. This leads Gokcumen to believe that the filaggrin mutation may have proliferated in East Asia for the sake of preserving the hornerin mutation. As he explains, large sections of the genome are often lost or inherited together during evolution, so genes like those for hornerin and filaggrin that are close to each other often share an evolutionary history.

While the research did not draw concrete conclusions about why the hornerin mutation was so important, changes in the hornerin gene can affect healthy skin function, influencing microbiome diversity on the skin.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!