After years of progress, the median earnings gap between black and white men has returned to what it was in 1950, according to new research by economists from Duke University and the University of Chicago.

The experience of African-American men is not uniform, though: The earnings gap between black men with a college education and those with less education is at an all-time high, the authors say.

The research appears online this week in the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper series.

The paper looks at earnings for working-age men across a span of 75 years, from 1940 to 2014. The earnings gap between black and white men narrowed during the civil rights era. Then, starting around 1970, the gap between black and white men’s wages started widening once again.

“When it comes to the earnings gap between black and white men, we’ve gone all the way back to 1950,” said Duke economist Patrick Bayer, who co-authored the paper with Kerwin Kofi Charles of the University of Chicago.

The picture for black men looks very different at the top of the economic ladder versus the bottom, the authors say. Since the 1960s, top black salaries have continued to climb. Those advances were fueled by more equal access to universities and high-skilled professions, the study finds.

Meanwhile, a starkly different story transpired at the bottom of the economic ladder. Massive increases in incarceration rates and the general decline of working-class jobs have devastated the labor market prospects of men with a high school degree or less, the authors say.

The changing economy has been hard on all workers with less than a high school education, but especially devastating for black men, Bayer said.

“The broad economic changes we’ve seen since the 1970s have clearly helped people at the top of the ladder,” Bayer said. “But the labor market for low-skilled workers has basically collapsed.

“Back in 1940 there were plenty of jobs for men with less than a high school degree. Now education is more and more a determinant of who’s working and who’s not.”

In fact, more and more working-age men in the United States aren’t working at all. The number of nonworking white men grew from about 8 percent in 1960 to 17 percent in 2014. The numbers look still worse among black men: In 1960, 19 percent of black men were not working; in 2014, that number had grown to 35 percent of black men. That includes men who are incarcerated as well those who can’t find jobs.

“The rate at which men are not working has been skyrocketing, and it’s not simply the result of the Great Recession,” Bayer said. “It’s a big part of what’s been happening to our economy over the past 40 years.”

The situation would be even worse if not for educational gains among African-Americans over the past 75 years, Bayer said.

On average, black men today have many more years of schooling than black men of the past, and the education gap between white and black men has shrunk considerably. Nevertheless, a gap remains: These days, black men have about a year’s less education than white men, on average.

“In essence, the economic benefits that should have come from the substantial gains in education for black men over the past 75 years have been completely undone by the changing economy, which exacts an ever steeper price for the differences that still remain,” Bayer said.

The findings show the need for renewed focus on closing racial gaps in education and school quality, which have been stuck in place for several decades, according to the authors. They also suggest that any economic changes that improve prospects for all low-skilled workers will have the important side effect of reducing racial economic inequality.

“We clearly need to create better job opportunities for everyone in the lower rungs of the economic ladder, where work has become increasingly hard to come by,” Bayer said.

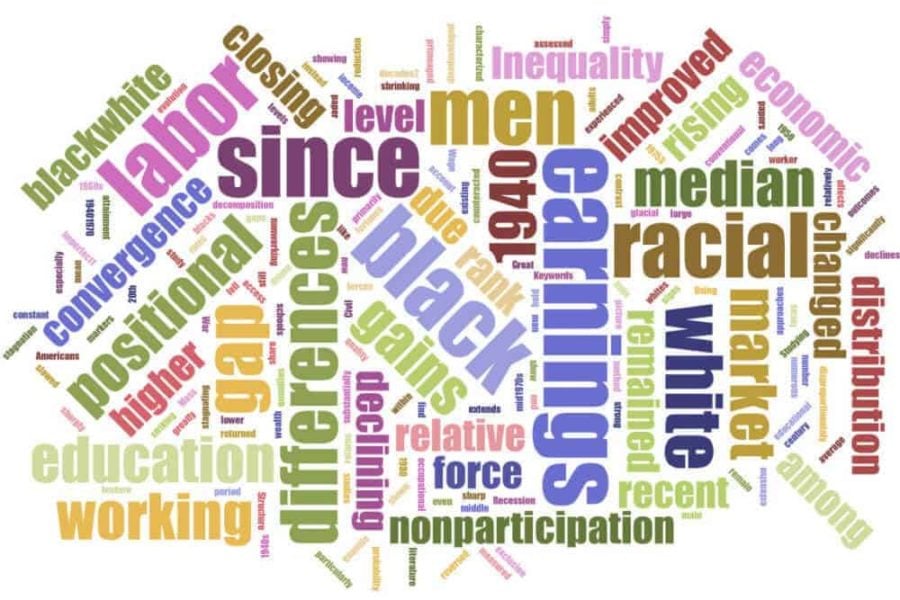

CITATION: “Divergent Paths: Structural Change, Economic Rank, and the Evolution of Black-White Earnings Differences, 1940-2014,” Patrick Bayer and Kerwin Kofi Charles. NBER Working Paper No. 2279, November 2016.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!