Anyone who has taken high school biology has likely come into contact with a ciliate. The much-studied paramecium is one of 7,000 species of ciliates, a vast group of microorganisms that share a common morphology: single-celled blobs covered in tiny hairs, or cilia. These cilia — Greek for “eyelash” — are used to propel a microbe through water and catch prey.

Today these hairy microbes are ubiquitous in marine environments. However, it’s unclear how long ciliates have inhabited Earth: After they die, members of most species simply disintegrate in their watery environs, leaving behind no fossilized remains.

Now, geologists at MIT and Harvard University have unearthed rare, flask-shaped microfossils dating back 635 to 715 million years, representing the oldest known ciliates in the fossil record. The remains are more than 100 million years older than any previously identified ciliate fossils, and the researchers say the discovery suggests early life on Earth may have been more complex than previously thought. What’s more, they say such prehistoric microbes may have helped trigger multicellular life, and the evolution of the first animals.

“These massive changes in biology and chemistry during this time led to the evolution of animals,” says Tanja Bosak, the Cecil and Ida Green Career Development Assistant Professor in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. “We don’t know how fast these changes occurred, and now we are finding evidence of an increase in complexity.”

Bosak and her colleagues have reported their findings in a paper posted online this week in the journal Geology.

Life’s rocky road

The group discovered the fossils in rocks from southwestern Mongolia. In 2008, Francis Macdonald, an assistant professor of geology at Harvard and the paper’s co-author, hiked through the Tsagaan Oloom Formation, a rocky terrain full of glacial deposits. These deposits are remnants from the two most severe ice ages, or “Snowball Earth” events, during the Cryogenian period, 635 to 715 million years ago. Relatively few fossils have been found from this time, making it difficult for geologists to pinpoint exactly what lived during this period.

Macdonald brought rock samples back to Cambridge, where Bosak and her colleagues began a meticulous hunt for tiny fossils. The team dissolved sections of rock in acid, then combed through the residue, looking for interesting shapes under the microscope.

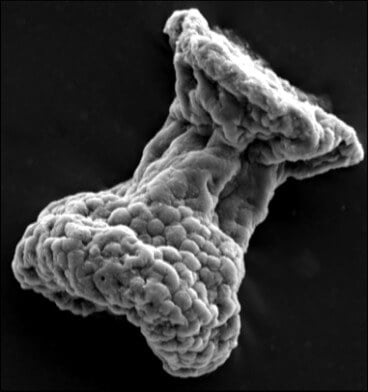

The team soon uncovered hundreds of “beautifully preserved” fossils resembling miniature flasks, Bosak says, with constricted necks and flaring collars. Each fossil was covered in bubble-like structures. Bosak compared the fossils with modern organisms, finding a nearly perfect match in a group of ciliates called tintinnids.

Shell life

Unlike most ciliates, tintinnids have a tough, vase-like shell that’s both resistant and flexible. A tintinnid lives within this shell, reaching out through the opening with hair-like appendages to draw food in. The bubbles on the shell’s surface serve as flotation devices, keeping the microbe afloat as its cilia propel it through water.

Because of their thick shells, tintinnids are rare ciliates that fossilize. While most unprotected ciliates simply dissolve away, the resistant organic shells of tintinnids can sink to the ocean bottom. Bosak says it’s this deposition of carbon that may have contributed to the evolution of the first animals.

“You have this resistant material that sinks to anaerobic oceans, where it takes longer to degrade,” Bosak says. “As a result, you could sequester more carbon … that in turn releases more oxygen.”

More oxygen in the atmosphere would foster complex, oxygen-breathing life. According to Bosak, the geologic timing is consistent with this theory: The ciliate fossils date to the period between the two ice ages; soon after the second ice age, fossils of the first animal embryos were identified.

The appearance of tintinnids as early as the Cryogenian period suggests other organisms may have existed as well, possibly setting the stage for animal evolution.

“Having found this, we know other things should have been there, possibly not leaving a fossil record,” Bosak says. “And this really shows there could have been much more going on than we thought.”

Nicholas Butterfield, a lecturer in paleobiology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., says the group’s findings provide convincing evidence for ancient organisms that are “significantly similar” to modern ciliates. However, in his view, the fossils mark a minimum date for the evolutionary appearance of tintinnids — the hairy organisms could have been floating about hundreds of millions of years earlier.

“It’s conceivable that they only evolved, or became ecologically important, at this time,” says Butterfield, who was not involved in the research. “Ciliates probably do play an important role in how the oceans work, but there’s no reason to believe that that role wasn’t defined much earlier.”

The team plans to examine the shells of tintinnids more closely, and will perform chemical analyses to understand what kinds of conditions might have prompted such shells to evolve. The researchers will also measure the carbon composition of individual fossils from different strata to identify exactly how carbon might have cycled, and what changes might have occurred leading up to the first animals.

“This provides some hope that we can actually start looking at biological changes,” Bosak says. “There is a record of these changes, and that’s what we’re showing by finding these fossils.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!