To say that UC San Diego archaeologist Geoffrey Braswell was surprised to discover a precious jewel in Nim Li Punit in southern Belize is something of an understatement.

“It was like finding the Hope Diamond in Peoria instead of New York,” said Braswell, who led the dig that uncovered a large piece of carved jade once belonging to an ancient Maya king. “We would expect something like it in one of the big cities of the Maya world. Instead, here it was, far from the center,” he said.

The jewel—a jade pendant worn on a king’s chest during key religious ceremonies—was first unearthed in 2015. It is now housed at the Central Bank of Belize, along with other national treasures. Braswell recently published a paper in the Cambridge University journal Ancient Mesoamerica detailing the jewel’s significance. A second paper, in the Journal of Field Archaeology, describes the excavations.

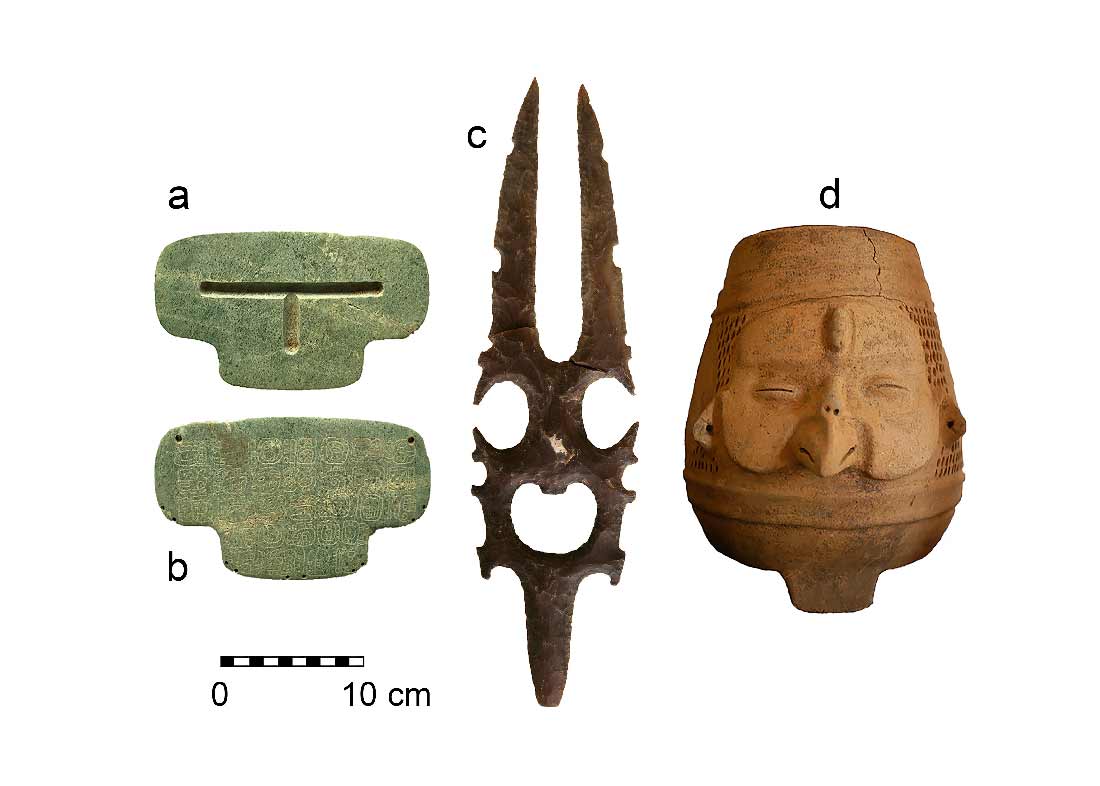

Three of the objects buried together by the Maya around A.D. 800. Why were they entombed? Field and artifact photos courtesy Braswell.

Three of the objects buried together by the Maya around A.D. 800. Why were they entombed? Field and artifact photos courtesy Braswell.

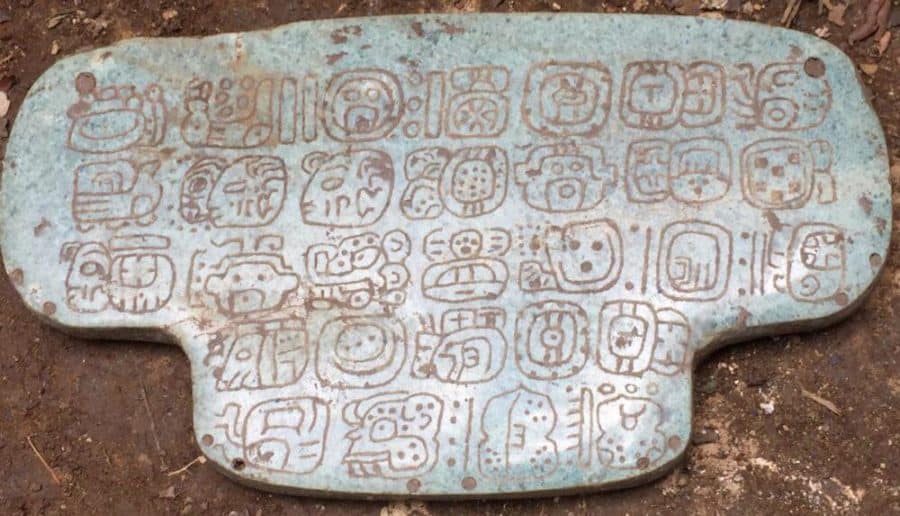

The pendant is remarkable for being the second largest Maya jade found in Belize to date, said Braswell, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at UC San Diego. The pendant measures 7.4 inches wide, 4.1 inches high and just 0.3 inches thick. Sawing it into this thin, flat form with string, fat and jade dust would have been a technical feat. But what makes the pendant even more remarkable, Braswell said, is that it’s the only one known to be inscribed with a historical text. Carved into the pendant’s back are 30 hieroglyphs about its first owner.

“It literally speaks to us,” Braswell said. “The story it tells is a short but important one.” He believes it may even change what we know about the Maya.

Also important: The pendant was “not torn out of history by looters,” said Braswell. “To find it on a legal expedition, in context, gives us information about the site and the jewel that we couldn’t have otherwise had or maybe even imagined.”

Where the jewel was found

Nim Li Punit is a small site in the Toledo District of Belize. It sits on a ridge in the Maya Mountains, near the contemporary village of Indian Creek. Eight different types of parrot fly overhead. It rains nine months of the year.

Nim Li Punit was abandoned within a generation of the construction of the tomb that held the jade pendant.

Nim Li Punit was abandoned within a generation of the construction of the tomb that held the jade pendant.

On the southeastern edge of the ancient Maya zone (more than 250 miles south of Chichen Itza in Mexico, where similar but smaller breast pieces have been found), Nim Li Punit is estimated to have been inhabited between A.D. 150 and 850. The site’s name means “big hat.” It was dubbed that, after its rediscovery in 1976, for the elaborate headdress sported by one of its stone figures. Its ancient name might be Wakam or Kawam, but this is not certain.

Braswell, UC San Diego graduate students Maya Azarova and Mario Borrero, along with a crew of local people, were excavating a palace built around the year 400 when they found a collapsed, but intact, tomb. Inside the tomb, which dates to about A.D. 800, were 25 pottery vessels, a large stone that had been flaked into the shape of a deity and the precious jade pectoral. Except for a couple of teeth, there were no human remains.

What was it doing there?

The pendant is in the shape of a T. Its front is carved with a T also. This is the Mayan glyph “ik’,” which stands for “wind and breath.” It was buried, Braswell said, in a curious, T-shaped platform. And one of the pots discovered with it, a vessel with a beaked face, probably depicts a Maya god of wind.

The most important aspect of the jewel, Braswell says, is a historical text of 30 hieroglyphs on its back, a private message seen mostly by the king who wore it.

The most important aspect of the jewel, Braswell says, is a historical text of 30 hieroglyphs on its back, a private message seen mostly by the king who wore it.

Wind was seen as vital by the Maya. It brought annual monsoon rains that made the crops grow. And Maya kings—as divine rulers responsible for the weather—performed rituals according to their sacred calendar, burning and scattering incense to bring on the wind and life-giving rains. According to the inscription on its back, Braswell said, the pendant was first used in A.D. 672 in just such a ritual.

Two relief sculptures on large rock slabs at Nim Li Punit also corroborate that use. In both sculptures, a king is shown wearing the T-shaped pendant while scattering incense, in A.D. 721 and 731, some 50 and 60 years after the pendant was first worn.

By the year A.D. 800, the pendant was buried, not with its human owner, it seems, but just with other objects. Why? The pendant wasn’t a bauble, Braswell said, “it had immense power and magic.” Could it have been buried as a dedication to the wind god? That’s Braswell’s educated hunch.

Maya kingdoms were collapsing throughout Belize and Guatemala around A.D. 800, Braswell said. Population levels plummeted. Within a generation of the construction of the tomb, Nim Li Punit itself was abandoned.

“A recent theory is that climate change caused droughts that led to the widespread failure of agriculture and the collapse of Maya civilization,” Braswell said. “The dedication of this tomb at that time of crisis to the wind god who brings the annual rains lends support to this theory, and should remind us all about the danger of climate change.”

Still and again: What was it doing there?

The inscription on the back of the pendant is perhaps the most intriguing thing about it, Braswell said. The text is still being analyzed by Braswell’s coauthor on the Ancient Mesoamerica paper, Christian Prager of the University of Bonn. And Mayan script itself is not yet fully deciphered or agreed upon.

Graduate student Mario Borrero excavates the substructure of the palace building which held the tomb.

Graduate student Mario Borrero excavates the substructure of the palace building which held the tomb.

But Prager and Braswell’s interpretation of the text so far is this: The jewel was made for the king Janaab’ Ohl K’inich. In addition to noting the pendant’s first use in A.D. 672 for an incense-scattering ceremony, the hieroglyphs describe the king’s parentage. His mother, the text implies, was from Cahal Pech, a distant site in western Belize. The king’s father died before aged 20 and may have come from somewhere in Guatemala.

It also describes the accession rites of the king in A.D. 647, Braswell said, and ends with a passage that possibly links the king to the powerful and immense Maya city of Caracol, located in modern-day Belize.

“It tells a political story far from Nim Li Punit,” Braswell said. He notes that Cahal Pech, the mother’s birthplace, for example, is 60 miles away. That’s a five-hour bus ride today, and back then would have been many days’ walk—through rainforest and across mountains. How did the pendant come to this outpost?

While it’s possible it had been stolen from an important place and whisked away to the provinces, Braswell doesn’t think so. He believes the pendant is telling us about the arrival of royalty at Nim Li Punit, the founding of a new dynasty. The writing on the pendant is not particularly old by Maya standards, but it’s the oldest found at Nim Li Punit so far, Braswell said. It’s also only after the pendant’s arrival that other hieroglyphs and images of royalty begin to show up on the site’s stelae, or sculptured stone slabs.

It could be that king Janaab’ Ohl K’inich himself moved to Nim Li Punit, Braswell said. Or it could be that a great Maya state was trying to ally with the provinces, expand its power or curry favor by presenting a local king with the jewel. Either way, Braswell believes, the writing on the pendant indicates ties that had been previously unknown.

“We didn’t think we’d find royal, political connections to the north and the west of Nim Li Punit,” said Braswell, who has been excavating in Belize since 2001 and at Nim Li Punit since 2010. “We thought if there were any at all that they’d be to the south and east.”

Even if you ignore the writing and its apparent royal provenance, the jade stone itself is from the mountains of Guatemala, southwest of Belize. There are few earlier indications of trade in that direction either, Braswell said.

We may never know exactly why the pendant came to Nim Li Punit or why it was buried as it was, but Braswell’s project to understand the site continues. He plans to return in the spring of 2017. This time, he also wants to see if he might discover a tie to the Caribbean Sea. After all, that’s a mere 12 miles downriver, a four-hour trip by canoe.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!