With graphene, Rutgers researchers have discovered a powerful way to cool tiny chips – key components of electronic devices with billions of transistors apiece.

“You can fit graphene, a very thin, two-dimensional material that can be miniaturized, to cool a hot spot that creates heating problems in your chip, said Eva Y. Andrei, Board of Governors professor of physics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy. “This solution doesn’t have moving parts and it’s quite efficient for cooling.”

The shrinking of electronic components and the excessive heat generated by their increasing power has heightened the need for chip-cooling solutions, according to a Rutgers-led study published recently in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Using graphene combined with a boron nitride crystal substrate, the researchers demonstrated a more powerful and efficient cooling mechanism.

“We’ve achieved a power factor that is about two times higher than in previous thermoelectric coolers,” said Andrei, who works in the School of Arts and Sciences.

The power factor refers to the effectiveness of active cooling. That’s when an electrical current carries heat away, as shown in this study, while passive cooling is when heat diffuses naturally.

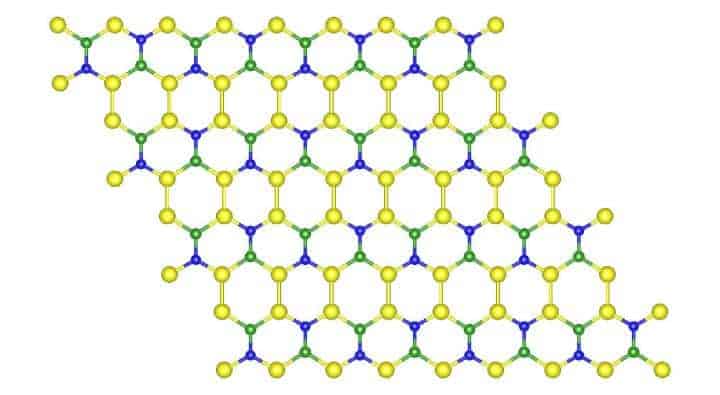

Graphene has major upsides. It’s a one-atom-thick layer of graphite, which is the flaky stuff inside a pencil. The thinnest flakes, graphene, consist of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice that looks like chicken wire, Andrei said. It conducts electricity better than copper, is 100 times stronger than steel and quickly diffuses heat.

The graphene is placed on devices made of boron nitride, which is extremely flat and smooth as a skating rink, she said. Silicon dioxide – the traditional base for chips – hinders performance because it scatters electrons that can carry heat away.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!