Researchers know that one problem in fighting diabetes is that at a certain point, big fat stores in a person stop ‘talking’ to the rest of the body. Now scientists are looking at whether a simple sponge inserted into the fat could in essence ‘wake’ it up by getting the fat to once again communicate, chemically speaking.

The novel, relatively simple approach implants a polymer sponge into fat tissue, reducing weight gain and blood-sugar levels in mice raised to have diabetes-like symptoms.

Said Michael Gower, Ph.D., of the University of South Carolina: “We’re approaching diabetes as tissue engineers…. When people eat poorly, don’t exercise and are under a lot of stress, they gain weight. When fat stores get too large, communication with other parts of the body breaks down and can lead to diabetes. What we’re trying to do is restart that conversation.”

In recent years researchers have come to understand that far from a simple, passive store of excess energy, body fat is itself an endocrine organ that plays a central role in energy regulation and helps other organs respond to blood sugar and insulin. In people with diabetes, certain high-needs tissues and organs lose their ability to take up they sugar they need to properly function. The result is glucose levels rise in the blood, leading to hyperglycemia.

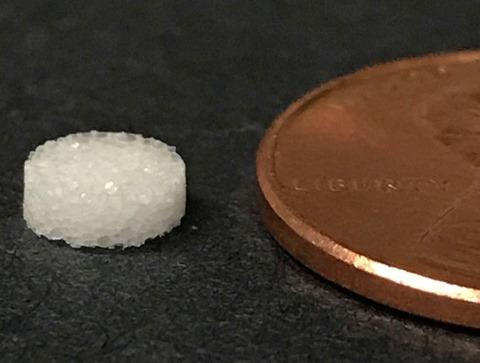

Previously Gower and colleagues had used a sponge imbued with pancreatic islet cells into fat pads of mice with diabetes-like symptoms. This time they wanted to see whether the sponge alone could to restart communication between fat and the rest of the body. (The sponges are made from the biocompatible material poly(lactide-co-glycolide), or PLG, used in medical stents.)

Within one week of getting implants in their abdominal fat pads, the mice’s fat cells, immune cells and blood vessels filled the pores of the sponge.And three weeks later, after having been fed a high-fat diet, the sponge mice showed a 10 percent gain in body fat, compared to a 30 percent gain in control animals.

Treated mice with sponges placed in their calves likewise had 60 percent more of of a protein that helps transfer blood sugar into muscles, compared to untreated mice. They also had lower blood sugar levels than the controls.

Said Gower: “I think what’s really exciting about this work and its implications is that we’re looking at how implanting this biomaterial in fat tissue, which has the ability to communicate with other organs, is affecting the whole body.”

Researchers found no negative side effects from the sponge implants, and now want to identify why the PLG sponge has such an effect. They also want to see if they can enhance the effect by adding bioactive molecules to the sponges — including the red-wine molecule resveratrol.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!