The men who were tried for their role in the 1994 Rwandan genocide that killed up to 1 million people want you to know that they’re actually very good people.

That’s the most common way accused men try to account for their actions in testimony before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, a new study has found.

Researchers examined more than 10,000 pages of testimony from 27 defendants at the ICTR to determine how these men tried to explain their involvement in the genocidal violence.

They found that an “appeal to good character” was used by defendants more than all other explanations combined to say why they weren’t guilty of the horrible crimes they were accused of committing.

“Genocide has been called the crime of crimes, and these accused perpetrators very much understood that,” said Hollie Nyseth Brehm, co-author of the study and assistant professor of sociology at The Ohio State University.

“They were trying to protect their reputation. Rather than acknowledging their role, they emphasized what good people they were and talked about their good deeds and admirable character traits.”

Nyseth Brehm conducted the study with Emily Bryant of Boston University, Emily Brooke Schimke of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Christopher Uggen of the University of Minnesota. Their results appear online in the journal Social Problemsand will be published in a future print edition.

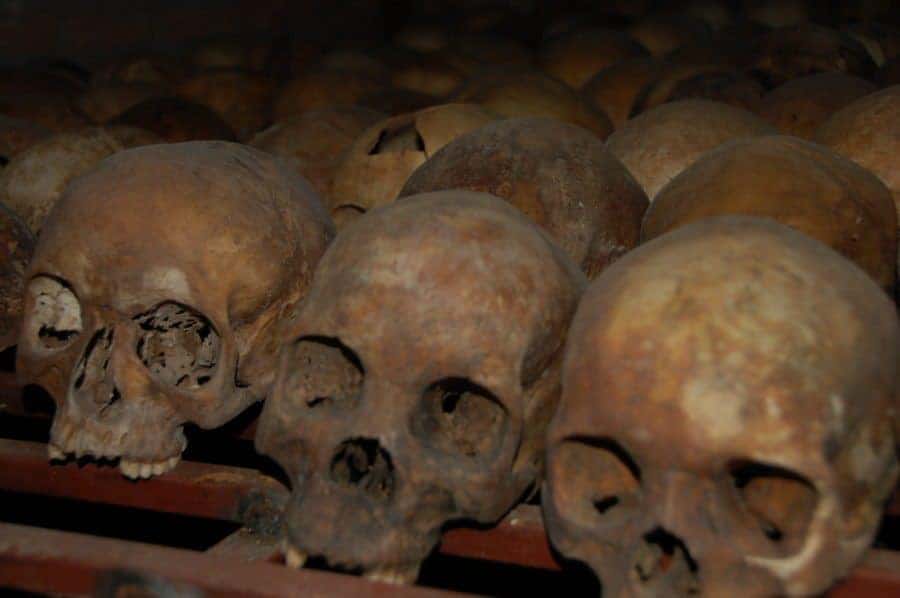

In 1994, mass violence claimed up to 1 million lives in the East African nation of Rwanda. Most of the victims were Tutsi, killed by the majority Hutus. The United Nations created the ICTR and, between 1995 and 2015, 75 individuals were tried for planning and executing the violence.

For this study, the researchers focused on 27 defendants, all men, who testified on their own behalf for one to 17 days. They were political leaders, military leaders or wealthy businessmen. Nearly all were indicted for complicity in genocide and either genocide or conspiracy to commit genocide. Within this sample, 19 defendants received sentences and eight were acquitted. Convicted defendants received sentence ranging from 12 years to life in prison.

The researchers analyzed the testimony using a classic criminology theory that suggests people use five specific techniques to neutralize their guilt and justify their participation in criminal activities.

The techniques are denial of responsibility, denial of injury, denial of the victim, condemnation of the condemners and appeal to higher loyalties.

“When it comes to genocide, we like to think that the perpetrators are irredeemably evil, but they are not – they are psychologically normal people who are acting this way under social circumstances,” Nyseth Brehm said.

“After it is over, perpetrators use these and other techniques to explain to their friends and family – and themselves – why they behaved the way they did.”

The findings showed that the defendants used only two of these techniques frequently: denial of responsibility and condemnation of the condemners (attacking those who criticize them).

But they found two neutralization techniques that had not been identified before, one of them being appeal to good character.

“They argued that they were such good people that they couldn’t be guilty of genocidal crimes,” Nyseth Brehm said. “They often talked about how they actually saved Tutsis from the violence and advocated for peace.”

One defendant, talking about massacres near where he lived, testified, “I was saddened by that news as well as frightened.… I did not have enough means to act in that situation. However, I did not fold my arms. I did what I had to do and what I could do.”

Another way they asserted their good character was to say they had nothing against the Tutsis. “I never said the Tutsi are not full-fledged human beings,” one defendant said.

“Rather than acknowledging the bad things they had done, the defendants often tried to talk about their traits and actions that proved what good people they are,” Nyseth Brehm said.

The other new technique the researchers identified was victimization. The defendants would talk about how they and their family and friends were targeted for being Hutus. One former mayor who was tried said, “I felt it was possible for me to die because I had been under permanent threat. I was being persecuted.”

While some Hutus were indeed killed in Rwanda, Nyseth Brehm said that nearly all the violence was targeted against Tutsis.

The researchers found that more than one-third of defendants used the victimization and appeals to good character techniques between one and 12 times per day of testimony.

Defendants relied especially heavily on the appeal to good character technique – in fact, results showed that this technique was employed more than all the classic techniques combined.

Why were these two new neutralization techniques not identified earlier?

Nyseth Brehm said most studies that have examined genocidal violence have tried to theorize what perpetrators were thinking before the crime. This study is one of the few to highlight their explanations after the crimes.

“We were looking not at what enabled them to commit the crime, but how they made sense of it afterward. How could they justify what they did?” she said.

In other research she has done in Rwanda, Nyseth Brehm said she has seen how people involved in genocide have dealt with their guilt in ways consistent with this study.

“A lot of the people I have talked to in Rwanda have to convince themselves that they are good people as a way to move forward. They have difficulty coming to terms with what they did.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!