A dusty, blackened thigh bone that may represent a “missing link” in human evolution was rejected from a major anthropologist conference this month, prompting frustration among the anthropology community and adding to the confusion surrounding a now-infamous specimen.

Scientists still don’t know exactly when humans diverged from other apes on the evolutionary tree. Most anthropologists agree that the most recent species from which both hominids and other apes descended — the “chimpanzee-human last common ancestor,” or CHLCA — which lived between four and ten million years ago.

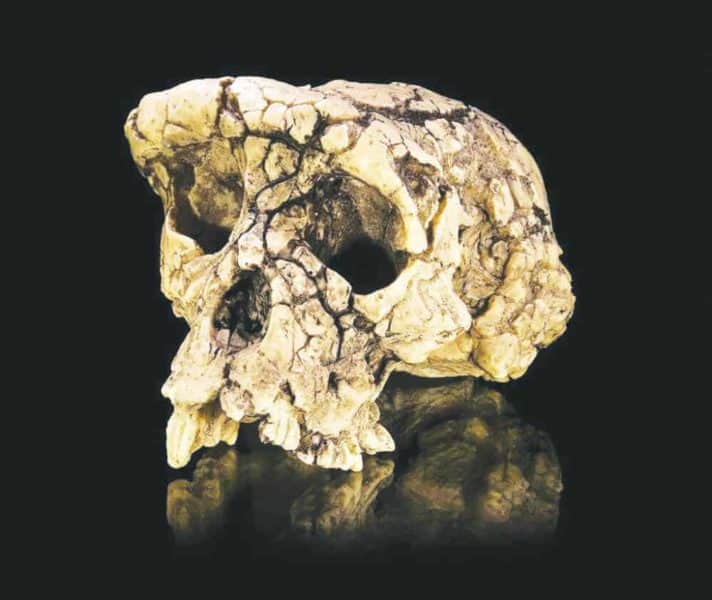

Sahelanthropus tchadensis, an early hominid species that lived around seven million years ago, is a strong candidate for the CHLCA, because it has a mix of chimp-like and human traits. Like chimpanzees, Sahelanthropus had a small brain, a strongly ridged brow, and an elongated skull, according to the Smithsonian. Like humans, Sahelanthropus had small teeth and a short facial structure.

Most significantly, Sahelanthropus‘s skull would have connected to its spinal cord at the bottom, not the back. Sahelanthropus shares this trait with a more recent human relative, Orrorin tugenensis, and may be Orrorin‘s ancestor. In Orrorin, the skull opening at the bottom allowed it to stand up straight and walk on two legs; Orrorin was confirmed bipedal in 2002 by scientists who examined Orrorin leg bones. Was Sahelanthropus also bipedal? Or does it just have the skull structure that made bipedalism possible, later on down the line?

Knowing whether Sahelanthropus walked upright would help scientists fit the species and its probable descendants into the phylogenetic tree of human evolution. If Sahelanthropus is the CHLCA, it’s a direct ancestor of modern humans, which means Orrorin may be also. It’s unclear right now how Orrorin is related to us, but a few scientists believe that modern humans descended from a species of Orrorin – as opposed to a species of Australopithecus, which has been the dominant view for a century. If Sahelanthropus and Orrorin are our ancestors, and not Australopithecus, much of modern anthropology will be overturned.

However, it’s impossible for anthropologists to be certain whether Sahelanthropus walked upright, because no Sahelanthropus leg bones have ever been discovered.

Or have they?

In 2001, French scientist Michel Brunet’s expedition discovered a Sahelanthropus skull, along with some jaw fragments, in the African country of Chad. The specimen was named Toumaï and used to establish Sahelanthropus as a species. When Brunet’s paper describing Sahelanthropus was published, Brunet argued that the positioning of the hole in Toumaï’s skull alone established that Sahelanthropus was bipedal. He has maintained this position ever since.

The leader of the field team that uncovered the bones, retired geographer Alain Beauvilain, disagrees. He claims that a femur was found nearby, and that its characteristics suggest a species that was not bipedal.

This femur is surrounded by mystery and contradictions. First, in 2004, a series of papers were published on a controversy involving some of Toumaï’s teeth that called into question the methods of Brunet’s original research team. In 2008, Beauvilain argued in a paper that through ancient human interference, the bones had been moved from their original spot, calling into question Brunet’s estimation of their age and place of origin. But most importantly, the field photographs of the bones published in Brunet’s original paper are not photographs of the bones as they were found — the photographs are recreations, staged with casts of the bones. Not necessarily a sign of dishonesty, but an unusual choice.

But the most important mystery is this: despite Sahelanthropus‘s significance as a potential biped, none of the scientists who discovered or described Sahelanthropus has ever acknowledged the femur’s existence in print.

France’s National Center for Scientific Research even explicitly stated that no leg bones were found at the site. Most anthropologists, until recently, had no idea it existed. Even some of Toumaï’s discoverers have barely seen the femur. David Pilbeam, a paleoanthropologist at Harvard University, who was a co-author on Brunet’s original Toumaï paper, never got a chance to analyze it and only saw it briefly. “All I can recall is that it lacked ends and was very black,” he said.

Is this a scientific cover-up? The withholding of anthropological evidence?

Brunet has declined to comment. “Our studies are still in progress,” he wrote in a brief e-mail to Nature. “Nothing to say before publishing.” According to Nature, “the discovery of [Toumaï] made Brunet famous in France, and especially in Poitiers, where a street is named after him.”

After Brunet’s original expedition, the femur was quietly shipped to France with the rest of the bones and ended up in the collection of the University of Poitiers. Aude Bergeret, now director of the Museum of Natural History Victor-Brun in Montauban, France, came across the femur in storage in 2004, when she was a graduate student at the university. “I discovered the femur by chance,” she says. “I remember joking with another student, who told me, ‘You found Toumaï’s femur!’,” Bergeret says. “I realized when I saw Roberto Macchiarelli that this joke was probably based on reality.”

Bergeret asked Machiarelli, then head of the department of geosciences at the University of Poitiers, to help her study the bone. They compared it to other known hominin bones and reached a preliminary impression: the owner of this femur was not bipedal.

This year, Bergeret and Machiarelli submitted a report to the Anthropological Society of Paris that discussed their brief impressions of the femur, and argued that a formal in-depth, peer-reviewed analysis was needed. It would have been the first scientific publication to describe the femur, finally giving evidence-starved anthropologists real information — but their report was rejected without explanation.

Anthropologists are used to scientific understanding being impeded by incomplete evidence or unknown factors. But it’s less usual for the bureaucracy and politics of scientific publication to prevent unanimously coveted extant evidence from coming to light — at least with something as significant as the origins of humanity.

“We don’t know why it’s been kept secret,” says paleoanthropologist Bill Jungers, at Stony Brook University in New York. “Maybe it’s not even a hominid. Who… knows until someone can expose it.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!