In the near future, we may be able to predict the appearance of our children, or accurately create 3-D projections of someone at a crime scene using just a sample of DNA.

A joint study published on Feb. 19 between Penn State, KU Leuven, Belgium, Stanford University and University of Pittsburgh identified 15 genes which determine our facial features.

“We performed the first exhaustive genetic mapping for facial features in Europeans, using new methodology that looks at the face in a data driven way,” Mark Shriver, professor of anthropology at Penn State, said.

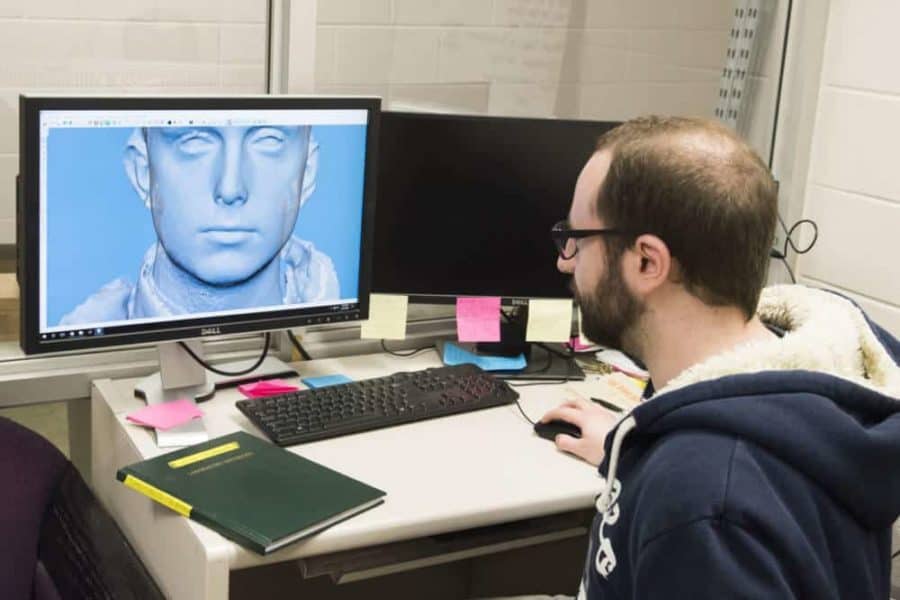

They first took 3-D images of the face and collected DNA samples. Then they divided the face into smaller modules and examined whether any locations in the DNA matched with variations in these modules.

“You have to scan the entire face in all its complexity,” Peter Claes, postdoctoral researcher in electrical engineering at KU Leuven, said. “So basically we came up with a technique to keep an unbiased vision, not only on the genome, but also on the facial variation.”

According to Shriver, most past studies looked at facial features using predetermined traits that were thought to be meaningful, like the width and length of the nose or the spacing between the eyes.

Shriver said these studies oversimplify what is a really complex group of different traits and features.

Instead, Shriver and his colleagues didn’t assume any features were more important than others. They started with over 7,000 facial variations, which they narrowed down using data reduction analysis to find which features actually have a significant impact on facial structure.

This allowed analysis of an unprecedented number of facial features.

Claes and Shriver have been working together for almost ten years now. In 2008, Shriver reviewed a paper partly written by Claes.

Shriver found Claes’ work interesting and applicable to his research, and they’ve been working together ever since.

Seven of the 15 identified genes are linked to the nose, which is a big break for predicting the appearance of the face.

“A skull doesn’t contain any traces of the nose, which only consists of soft tissue and cartilage,” Claes said.

Therefore, if forensic scientists wanted to reconstruct a face on the basis of a skull, the nose was always a primary obstacle.

But now, if they can retrieve DNA from the skull, it would be significantly easier to predict the shape of the nose.

The Stanford team found out that genomic loci (gene maps), linked to these facial features, are active when our face develops in the womb.

“Furthermore, we also discovered that different genetic variants identified in the study are associated with regions of the genome that influence when, where and how much genes are expressed,” Joanna Wysocka, professor of chemical and systems biology and of developmental biology at Stanford University, said to ScienceDaily.

These results have various implications. Facial recreations could be used in forensics to identify victims or perpetrators.

Bone remnants of early human populations, which contain DNA, could generate projections of our early ancestors.

We may even be able to predict the appearance of our children.

Some groups are already claiming to have these capabilities, but Shriver said these are hollow claims based on insufficient research.

“There are companies out there selling this stuff now – but it’s just not ready,” Shriver said. “They haven’t proved it works. What they’re doing is more forensic pseudoscience – forensic supernatural science.”

Shriver and his colleagues at Penn State collected data from about 10,000 individuals along with roughly 1,000 individuals from the University of Pittsburgh, but they still feel there’s a long way to go.

The Penn State team is starting a new study where they’ll be collecting data from an additional 1,000 individuals.

This study will expand upon their past observations and they’ll be recording not only facial features, but other characteristics such as hair type, skin pigmentation and vocal ranges.

Voice recordings can be compared with face structure to identify how the face relates to one’s voice — and therefore, how one’s genes affect their voice.

In all of these studies, Shriver said people tend to latch on to the idea of race affecting the variations they record.

“This makes people sometimes think of race and human population differences on that level. Really, this goes to prove that those ideas of very separate populations or even independent evolutions just don’t make sense,” Shriver said. “There’s physical differences on the surface of people, but that’s really where most of them are.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!