A research team led by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) found the fingerprint of a massive flood of fresh water in the western Arctic, thought to be the cause of an ancient cold snap that began around 13,000 years ago.

“This abrupt climate change—known as the Younger Dryas—ended more than 1,000 years of warming,” explains Lloyd Keigwin, an oceanographer at WHOI and lead author of the paper published online July 9, 2018, in the journal Nature Geocscience.

The cause of the cooling event, which is named after a flower (Dryas octopetala) that flourished in the cold conditions in Europe throughout the time, has remained a mystery and a source of debate for decades.

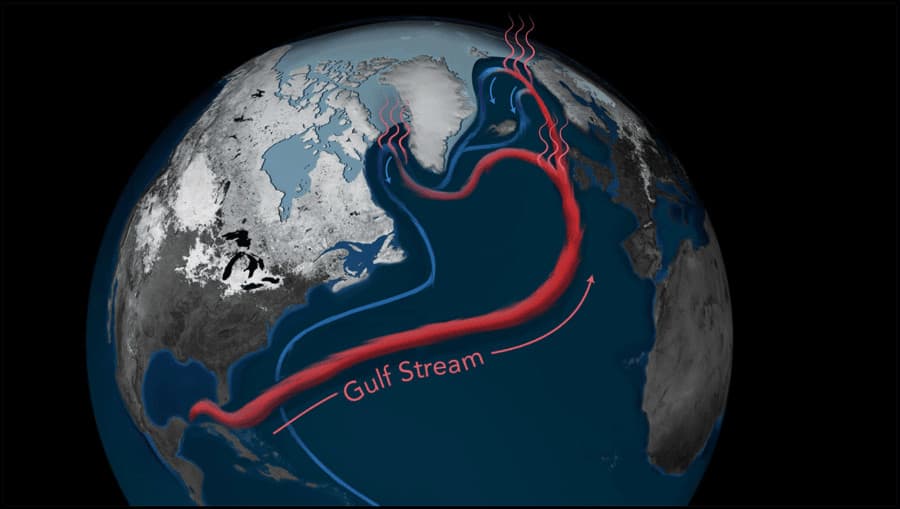

Many researchers believed the source was a huge influx of freshwater from melting ice sheets and glaciers that gushed into the North Atlantic, disrupting the deep-water circulation system — Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) — that transports warmer waters and releases heat to the atmosphere. However, geologic evidence tracing its exact path had been lacking.

In 2013, a team of researchers from WHOI, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, and Oregon State University, set sail to the eastern Beaufort Sea in search of evidence for the flood near where the Mackenzie River enters the Arctic Ocean, forming the border between Canada’s Yukon and Northwest territories. From aboard the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy, the team gathered sediment cores from along the continental slope east of the Mackenzie River. After analyzing the shells of fossil plankton found in the sediment cores, they found the long sought-after geochemical signal from the flood.

“The signature of oxygen isotopes recorded in foraminifera shells preserved in the sediment allowed us to fingerprint the source of the glacial lake discharge down the MacKenzie River 13,000 years ago,” said co-principal investigator Neal Driscoll, a professor of geology and geophysics at Scripps Oceanography. “Radiocarbon dating on the shells provided the age constraints. Circulation models for the Arctic Ocean reveal that low-salinity surface water is efficiently transported to the North Atlantic. How exciting it is when the pieces of a more than 100-year puzzle come together.”

Next steps in future research, Keigwin says, will be for scientists to answer remaining questions about the quantity of fresh water delivered to the North Atlantic preceding the Younger Dryas event and over how long of a period of time.

“Events like this are really important, and we have to understand them better,” adds Keigwin. “In the long run, I think the findings from this paper will stimulate more research on how much fresh water is really necessary to cause a change in the system and weakening of the AMOC. It certainly calls further attention to the warming we’re seeing in the Arctic today, and the accelerated melting of Greenland ice.”

Earlier this year, a paper by researchers at the University College London and WHOI found evidence that the AMOC hasn’t been running at peak strength since the mid-1800s and is currently at its weakest point in the past 1,600 years. Continued weakening could disrupt weather patterns from the U.S. and Europe to the African Sahel.

Additional co-authors of the paper published in Nature Geoscience are: Ning Zhao and Liviu Giosan of WHOI; Shannon Klotsko of Scripps Oceanography; and Brendan Reilly of Oregon State University.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation, Office of Polar Programs.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!