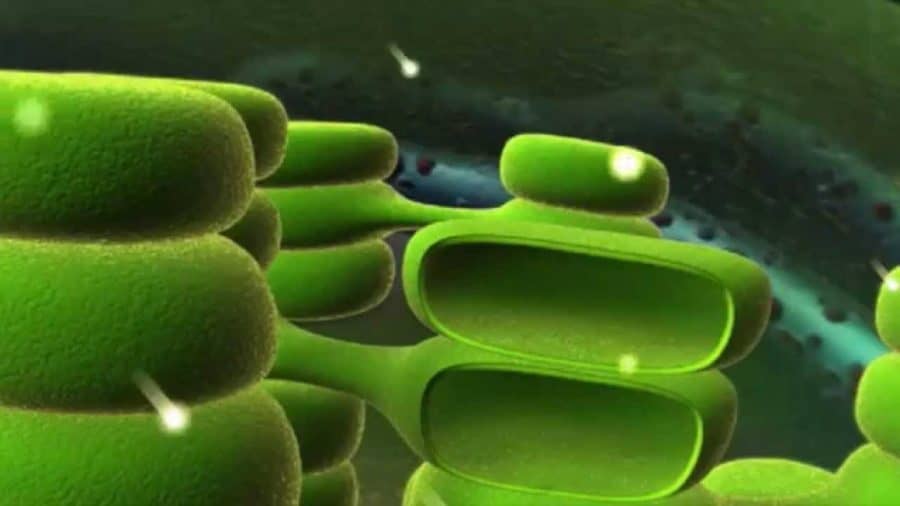

Photosynthesis is one of the most crucial life processes on Earth. It’s how plants get their food, using energy from sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide from the air into sugars. But scientists have long believed that more than 30 percent of the energy produced during photosynthesis is wasted in a process called photorespiration.

A new study by researchers at Cornell and the University of California, Davis, suggests that photorespiration wastes little energy and instead enhances nitrate assimilation, the process that converts nitrate absorbed from the soil into protein.

“Understanding the regulation of these processes is critical for sustaining food quality under climate change,” said lead author Arnold Bloom in the Department of Plant Sciences at UC Davis. The study was published July 2 in the journal Nature Plants.

During photorespiration, Rubisco, the most prevalent protein on the planet, combines sugars with oxygen in the atmosphere instead of carbon dioxide. This was thought to waste energy and decrease sugar synthesis. Researchers have speculated that photorespiration persists because most plants have reached an evolutionary dead end.

In the study, the researchers propose that something else is going on. Rubisco also associates with metals, either manganese or magnesium. When Rubisco associates with manganese, photorespiration proceeds along an alternative biochemical pathway, generates energy for nitrate assimilation and promotes protein synthesis. Nearly every recent test-tube study of Rubisco biochemistry, however, has been conducted in the presence of magnesium and absence of manganese, allowing only the less energy-efficient pathway for photorespiration.

“These are old enzymes that still have secrets to surrender. Future food security demands that we give these enzymes our attention,” said co-author Kyle Lancaster, Cornell associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology.

Added Bloom: “There’s a lot we can learn from observing what plants are doing that can give us clear messages of how we should proceed to develop crops that are more successful under the conditions we anticipate in the next few decades.”

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation and the John B. Orr Endowment.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!