By turning on a single gene, one that is found in all mammals, NIEHS scientists prompted male mice to grow ovaries. The study, published Sept. 18 in the journal Human Molecular Genetics, suggests that sexual development is flexible and may be able to shift in response to different genetic or environmental factors.

“It was originally thought that once the cells in the gonads commit to a certain fate — either testes or ovaries — that they had reached the point of no return. That male is male and female is female,” said senior study author Humphrey Hung-Chang Yao, Ph.D., head of the NIEHS Reproductive Developmental Biology Group. “But we and others found that testes and ovaries retain the ability to go down the opposite path of sexual development.”

The researchers tested the effects in mice by activating an ovary-promoting gene called FOXL2. Their findings could give insight into disorders of sexual development, such as ambiguous genitalia, undescended testicles, and infertility, which together affect as many as one in 5500 humans.

Determining sex

Among vertebrates, there is a wide variation in the signals that trigger sex determination of the gonads, which are the female and male reproductive organs that produce eggs and sperm, respectively. In some types of turtles and alligators, sex is shaped by environmental cues like temperature or the availability of nutrients. In humans, it is written in the composition of the chromosomes that package their DNA — XX for female, XY for male.

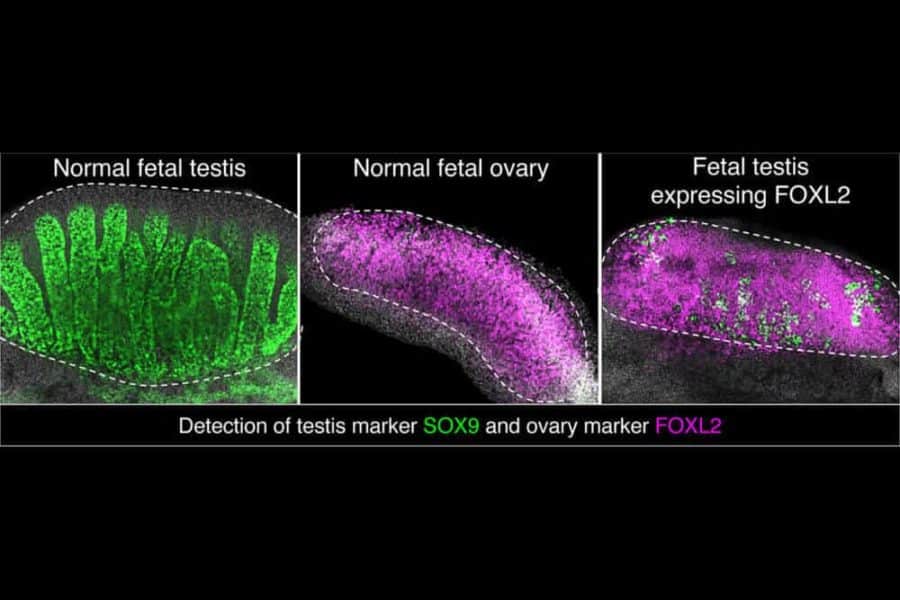

Although there are differences, many of these organisms use the same proteins to guide sexual development, like SRY and SOX9 in the testis, and WNT4 and FOXL2 in the ovary. In this study, Yao wanted to explore how FOXL2 directs ovarian development. FOXL2 is a kind of master switch that turns multiple genes on and off.

Barbara Nicol, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in his laboratory, used a technique called ChiP-seq to pinpoint the regions of the genome that are acted upon by FOXL2. She found that FOXL2 interacted with approximately 10,000 spots along the mouse genome in the ovary.

Then, she genetically engineered male mice — which had the chromosomal composition of XY — to produce FOXL2 in their testes. Their gonads morphed into ovaries, although they retained some molecular and structural features related to their original sex programming.

“This is an important finding,” said Francesco DeMayo, Ph.D., head of the NIEHS Reproductive and Developmental Biology Laboratory. “The identification of the fundamental biological mechanisms that regulate sexual development has implications in human fertility and for the impact the environment may have on this process.”

The road less traveled

The researchers are not the first to manipulate FOXL2 in mice. A previous teamknocked out, or suppressed, the gene in female mice, causing their ovaries to turn into testes. Nicol took her results and compared it with genetic data taken from the previous study to map out the regions of the genome responsible for the feminizing action of FOXL2.

“We know a lot about what is going on in sex determination of the testis, about the downstream partners for SRY and SOX9,” said Nicol, who is lead author of the paper. “That’s not the case for sex determination of the ovary. We know some of the components in the pathways, but the picture is incomplete. By finding the missing pieces in the puzzle of ovarian development, we hope to understand why something goes wrong and you have sex reversal or female infertility.”

Citations:

Nicol B, Grimm SA, Gruzdev A, Scott GJ, Ray MK, Yao HHC. 2018. Genome-wide identification of FOXL2 binding and characterization of FOXL2 feminizing action in the fetal gonads. Human Molecular Genetics. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy312. [Online 13 Sep 2018].

Garcia-Ortiz JE, Pelosi E, Omari S, Nedorezov T, Piao Y, Karmazin J, Uda M, Cao A, Cole SW, Forabosco A, Schlessinger D, Ottolenghi C. 2009. Foxl2 functions in sex determination and histogenesis throughout mouse ovary development. BMC Dev Biol 9:36.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!