Imagine fighting enemies that differ in their susceptibility to the weapon you are using against them. Some will perish, but others will survive the attack by implementing various defensive or offensive strategies and eventually will return.

Breast cancer cells behave in a similar manner. They vary remarkably in their ability to respond to therapy, which is one of the reasons cancer is difficult to treat.

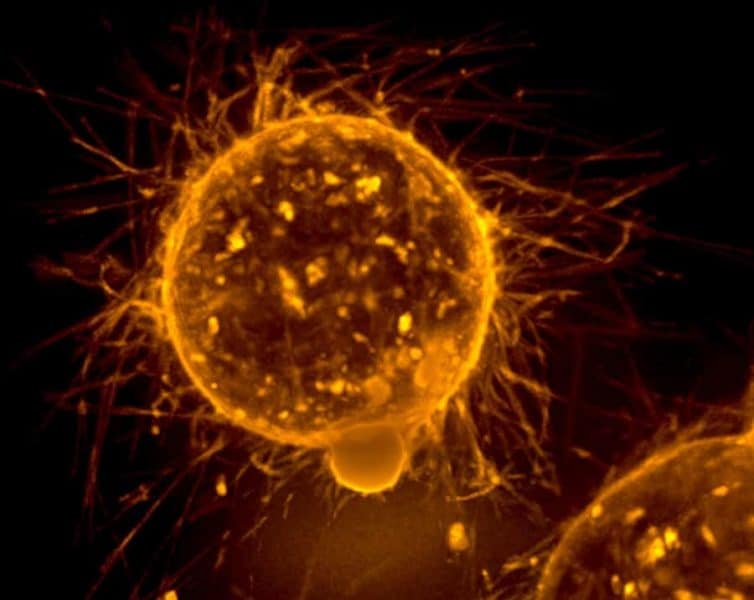

“One of the goals of my lab is to better understand the mechanisms that allow breast cancer cells to be so heterogeneous,” said Dr. Chonghui Cheng, associate professor at the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center, of molecular and human genetics and of molecular and cellular biology at Baylor College of Medicine. “In this study, we investigated cancer stem cells, a cell population that has the plasticity to generate cells with different properties, focusing on the cell surface protein CD44.”

CD44 is a well-known marker of cancer stem cells and one that is extensively studied in the Cheng lab. The CD44 gene can produce two different forms of the protein – CD44s and CD44v – via a process called alternative splicing. Cheng and her colleagues investigated whether there was a difference in the two forms of CD44 expressed in human breast cancer cells. They also wanted to know whether the different forms of CD44 contributed differently to the disease.

To answer their questions, Cheng and her colleagues took an unbiased approach. They conducted bioinformatics analyses of breast cancer patient data collected in the Cancer Genome Atlas database.

“Our analyses show that CD44s and CD44v, the two major forms of CD44 generated by alternative splicing, have distinct biological functions in breast cancer,” said Cheng, who also is a member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“Cancer cells expressing high levels of CD44s have properties of cancer stem cells – they tend to be metastatic or recurrent and to survive treatment. But when they switch to CD44v, they have fewer cancer stem cell properties but are engaged in proliferation. Alternative splicing is the mechanism that allows the CD44 proteins to switch,” Cheng said.

The researchers envision that by manipulating the levels of the two forms of CD44, it might be possible to change cancer cell properties in ways that may enhance cancer susceptibility to treatment.

“We anticipate that other genes that also undergo alternative splicing could as well contribute to the cells’ fate and to the plasticity that generates cancer heterogeneity,” Cheng said.

Find all the details of this study in the journal Genes & Development.

Other contributors to this work include Honghong Zhang, Rhonda L. Brown, Pu Zhao, Sali Liu, Xuan Liu, Yu Deng, Xiaohui Hu, Jing Zhang, Xin D. Gao, Yibin Kang, Arthur M. Mercurio and Hira Lal Goel. The authors are affiliated with one or more of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Princeton University and University of Massachusetts Medical School.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01CA182467, R01GM110146, R01CA203439 and T32CA080621, the Brewster Foundation, the Susan G. Komen Foundation and the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Rising Star Award RR160009.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!