Caenorhabditis elegans is a seemingly unimpressive worm. It is as long as a penny is thick, it lives in the soil feeding on microbes it finds on rotting vegetation and it is non-hazardous. But, in reality C. elegans is truly a treasure trove of information for researchers like Dr. Meng Wang, who search for clues on how to live healthier, longer lives.

“In my lab, we study the regulation of longevity using C. elegans as the animal model,” said Wang, a professor in the Huffington Center on Aging, of molecular and human genetics and Robert C. Fyfe Endowed Chair on Aging at Baylor College of Medicine. “In this study, we looked for answers at the cellular level, investigating how intracellular compartments of the cell work together to keep the cell healthy and living longer.”

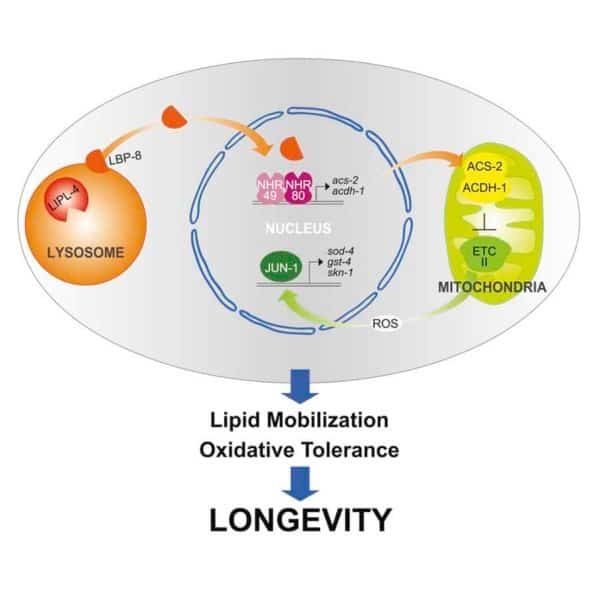

Wang and her colleagues specifically looked at two essential organelles, or compartments, of cells: the lysosomes, mostly known as the scavenger center of the cell that breaks down cellular materials and recycles them, and the mitochondria, the structures in charge of respiration producing energy for the cell.

“In our previous work we found a specific lysosomal lipid signaling pathway that promotes longevity,” said Wang, who also is a member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center and an investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “Here we found that inducing this lysosomal signaling pathway activates specific mitochondrial genes, which in turn trigger a metabolic switch from using glucose to using fat as energy source, as well as other responses.”

Cells can use either sugar or lipids as fuels, and switching from the former to the latter generates a number of cellular responses that improve metabolic fitness.

“Overall, the worms become leaner because they use lipids instead of sugar and at the same time they are better protected from oxidative damages. The result is that they have extended, healthier lifespan,” Wang said.

The researchers anticipate that other cellular organelles also communicate with each other in regulating healthy aging.

“Cellular organelles are very dynamic; they communicate with each other by physical interaction and/or by biochemical communication,” Wang said. “We think that during the aging process, this communication is disrupted, leading to a halt of communication or miscommunication between the organelles, which, in turn, can lead to metabolic problems, disease and aging. If we can understand how organelles communicate, we may find ways to help them to continue their conversation in ways that promote healthier, longer lives.”

Find all the details of this study in the journal Developmental Cell.

Other contributors to this work include Prasanna V. Ramachandran, Marzia Savini, Andrew K. Folick, Kuang Hu, Ruchi Masand and Brett H. Graham, who are all affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, March of Dimes Foundation, Welch Foundation, NIH grants (R01AG045183, R01AT009050 and DP1DK113644) and by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!