Genetically editing a cancer patient’s immune cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, then infusing those cells back into the patient appears safe and feasible based on early data from the first-ever clinical trial to test the approach in humans in the United States. Researchers from the Abramson Cancer Center have infused three participants in the trial thus far—two with multiple myeloma and one with sarcoma—and have observed the edited T cells expand and bind to their tumor target with no serious side effects related to the investigational approach. Penn is conducting the ongoing study in cooperation with the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and Tmunity Therapeutics.

“This trial is primarily concerned with three questions: Can we edit T cells in this specific way? Are the resulting T cells functional? And are these cells safe to infuse into a patient? This early data suggests that the answer to all three questions may be yes,” says the study’s principal investigator Edward A. Stadtmauer, section chief of Hematologic Malignancies at Penn. Stadtmauer will present the findings next month at the 61st American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition.

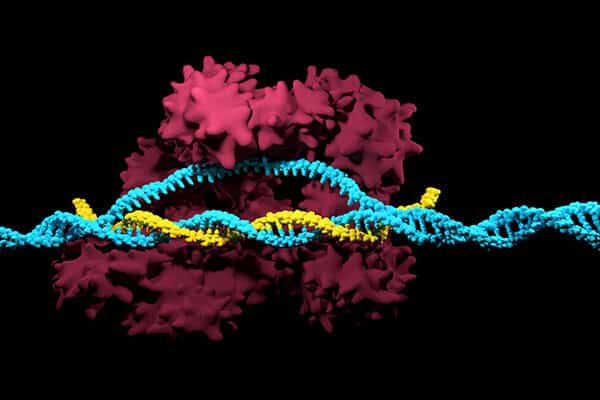

The approach in this study is closely related to CAR T cell therapy, which engineers patients’ own immune cells to fight their cancer, but it has some key differences. Just like CAR T, researchers begin by collecting a patient’s T cells through a blood draw. However, instead of arming these cells with a receptor like CD19, the team first uses CRISPR/Cas9 editing to remove three genes. The first two edits remove a T cell’s natural receptors to make sure the immune cells bind to the right part of the cancer cells. The third edit removes PD-1, a natural checkpoint that sometimes blocks T cells from doing their job.

“Our use of CRISPR editing is geared toward improving the effectiveness of gene therapies, not editing a patient’s DNA,” says the study’s senior author Carl June, the Richard W. Vague Professor in Immunotherapy and director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies in the Abramson Cancer Center. “We leaned heavily on our experience as pioneers of the earliest trials for modified T cell therapies and gene therapies, as well as the strength of Penn’s research infrastructure, to make this study a reality.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!