Firefighting foams — called aqueous film-forming foams — are used by the military to rapidly extinguish liquid fuel fires on airplanes and ships.

These foams contain fluorine in the form of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS. PFAS chemicals work as a surfactant — they lower the surface tension of water, allowing the foam to more effectively cut off the oxygen that feeds a fuel fire.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, PFAS is found in many products, such as clothing, carpets, fabrics for furniture, adhesives, paper packaging for food, and heat-resistant and non-stick cookware. PFAS chemicals are persistent in the environment and in the human body — meaning they don’t break down and they can accumulate over time. There is evidence that exposure to PFAS can lead to adverse human health effects, the EPA says.

Naval Research Lab scientists routinely test fluorine-free foams at Chesapeake Beach as part of their effort to find a replacement firefighting foam that meets military requirements.

They also test foams that contain fluorine, because the military still uses them to fight real liquid fuel fires.

The military no longer uses these foams for training.

John Farley, director of fire test operations at the lab, demonstrated a test in the facility’s 28-square-foot fire tank.

First, workers put an inch of water into the tank. Next, they added two gallons of ethanol-free gasoline, which floats on top of the water. The water helps to protect the test pan and ensures the test area is completely covered with fuel.

A worker then ignites the fuel, which produces a 5-megawatt fire. Farley said researchers then wait 10 seconds before attempting to extinguish the blaze with the foam, so the fire maintains a consistent burn.

The foam comes out of a nitrogen-pressurized nozzle at a set rate, so test results are consistent, he said.

During the test, Farley pushes the foam around the pool of fire to separate the vapor from the pool of gas. He said the gas in the pool doesn’t burn, just the vapor. Also, the foam barrier minimizes radiant heat going back into the fuel.

The military’s standard for a successful product, called MIL-SPEC, requires that a fire of the size of the test fire must be extinguished within 30 seconds.

Since the foam used contained fluorine, it met the MIL-SPEC with an extinction time of 27 seconds, Farley said.

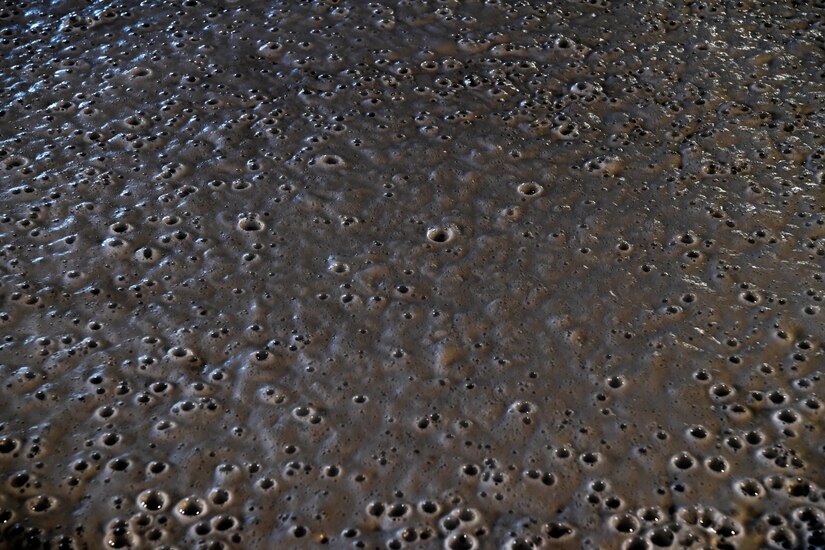

After the fire was extinguished, a foam layer floats over the fuel and water. At this point, researchers perform a second test — called a burn back — in which a bucket of gasoline is set in the middle of the tank and ignited.

The purpose of the burn back test is to measure how long it takes the foam to degrade and the fire to reignite over the pool.

After the test is over, Farley said a sample of the foam is measured by a dynamic foam analyzer, which computes the geometric structure of the foam.

If an effective firefighting foam is developed, the structure of the foam will be informative, particularly, since commercially developed foam makers don’t disclose their ingredients, he said.

Farley said the lab also conducts tests using the fluorine-free commercial foams. In a recent test, one foam being tested took 47 seconds to extinguish the fire, and the other took nearly one minute. Since neither met the MIL-SPEC of 30 seconds, they both failed.

After each test, workers wash the foam down with water and collect it inside a tank for incineration for safe disposal.

During all testing, the Annapolis, Maryland, fire marshal is present to ensure the tests are conducted safely.

Farley said each type of foam is tested 23 times — 22 in the 28-square-foot tank and once in the lab’s 58-square-foot tank.

He said he’s confident that a safe and effective firefighting foam will be developed in the years ahead.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!