Every time you open a weather app, watch a video on youtube, or search the internet for the best Thai food near you, you’re accessing and processing data with software stored on servers scattered around the world. This is what the tech industry calls “the cloud.”

Cloud computing hasn’t just changed how we use our phones or store our pictures. It has also changed how research is conducted, allowing scientists to, essentially, rent the computers necessary to store and process massive amounts of data. They don’t need to buy their own servers and banks of hard drives—they just pay for cloud services when they need them.

But even using hundreds of powerful computers linked on the cloud, the calculations necessary to model the changing climate or discover new potential drugs can take weeks, or even months, to run.

Researchers at Northeastern, Boston University, and the University of Massachusetts Amherst, are working together to build their own cloud computing testbed, to find ways to make this technology more effective and efficient.

“We’re trying to push the edge of cloud computing,” says Miriam Leeser, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at Northeastern. “What should the next generation of cloud services look like?”

Most cloud computing research is done by Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, says Peter Desnoyer, an associate professor of computer science, because those companies operate most cloud services.

“The insights they get from operating these large systems and observing users’ needs are key to many advances,” Desnoyer says. “Yet they’re also cautious, because they don’t want to disrupt service, making it hard for them to take large leaps.”

This cloud computing testbed will allow researchers to develop new and innovative cloud services, and simultaneously provide those services to the broader research community.

“There’s an infinite set of arbitrary things we could create—some of them are useful, most of them aren’t,” Desnoyers says. “Offering actual services to real users helps us find the innovations that are actually useful.”

So far, Leeser and Desnoyers have been awarded more than $1 million to support their aspects of the research.

Leeser’s focus is on the hardware. To process large amounts of data, most current cloud computing systems rely on graphics-processing units, known as GPUs, which were originally developed to render images. These chips can perform multiple calculations simultaneously (researchers call this “parallelism”), which makes them useful for running scientific simulations, as well as video games.

“People have gotten really good performance using GPUs,” Leeser says. “But they are also high power and the kind of parallelism they do is restricted.”

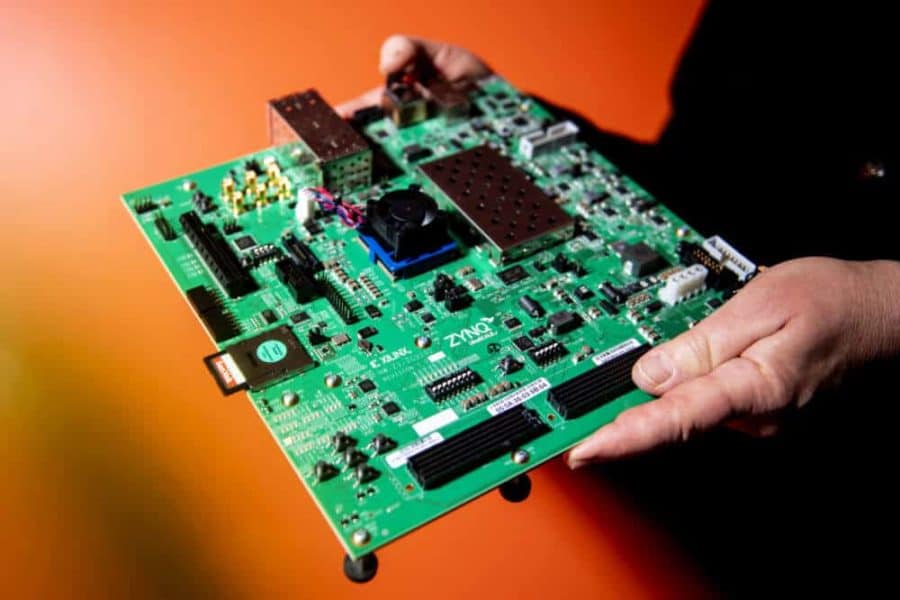

For this new testbed, Leeser is installing more flexible chips called field-programmable gate arrays, or FPGAs. These computer chips are more energy-efficient than graphics processing units, and their circuits aren’t fixed—they can be reconfigured any number of times to suit a researcher’s needs.

“It’s hardware you can program like it’s software,” Leeser says. “You can build a complete architecture that’s designed for the problem that you want to solve. It’s much more adaptive”

Desnoyers is working on the software, finding ways for researchers to efficiently share resources without interfering with each other. To effectively serve the larger community, the testbed must be able to temporarily isolate computers working on a specific problem or redirect resources from one group to another, while maintaining a secure system.

“We’re trying to unify it in a way that can handle the radically different ways that researchers use these systems,” Desnoyers says. “You can’t make something that works for everyone, but you can do a lot better than we do today. And the advantages are not just being able to operate your computers more efficiently; there’s also a huge gain in scientific collaboration that comes when scientists from different fields work together on these systems.”

The project is just getting started, but the plan is to grow it into a testbed that will support researchers around the country.

“The academic community has always had a strong role in the evolution of these technologies,” Desnoyers says. “Our goal is to enable computer scientists across all of this community to work on the research that will build the cloud of the future.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!