Mandarin Chinese is considered one of the hardest languages for native English speakers to learn, in part because the language—like many others around the world—uses distinctive changes in pitch, called “tones,” to change the meaning of words that otherwise sound the same. In the new study, published today in npj Science of Learning (a Nature partner journal), researchers significantly improved the ability of native English speakers to distinguish between Mandarin tones by using precisely timed, non-invasive stimulation of the vagus nerve—the longest of the 12 cranial nerves that connect the brain to the rest of the body. What’s more, vagus nerve stimulation allowed research participants to pick up some Mandarin tones twice as quickly.

“Showing that non-invasive peripheral nerve stimulation can make language learning easier potentially opens the door to improving cognitive performance across a wide range of domains,” said lead author Fernando Llanos, a postdoctoral researcher in Pitt’s Sound Brain Lab.

“This is one of the first demonstrations that non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation can enhance a complex cognitive skill like language learning in healthy people,” said Matthew Leonard, an assistant professor, Department of Neurological Surgery, UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences, whose team developed the nerve stimulation device. Leonard is a senior author of the new study, alongside Bharath Chandrasekaran, who is professor and vice chair of research in the Department of Communication Science and Disorders within Pitt’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and director of the Sound Brain Lab.

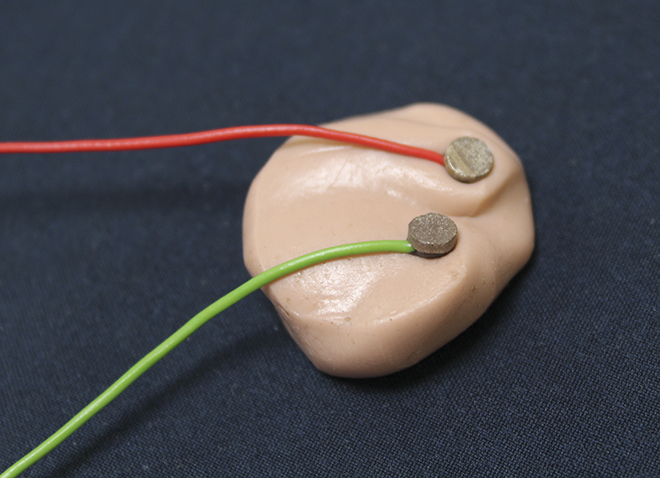

A small stimulator to deliver noninvasive transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation may have wide-ranging applications for boosting many kinds of learning. (Leonard Lab/UCSF/Jhia Louise Nicole Jackson)

Researchers used a non-invasive technique called transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS), in which a small stimulator is placed in the outer ear and can activate the vagus nerve using unnoticeable electrical pulses to stimulate one of the nerve’s nearby branches.For their study, the researchers recruited 36 native English-speaking adults and trained them to identify the four tones of Mandarin Chinese in examples of natural speech, using a set of tasks developed in the Sound Brain Lab to study the neurobiology of language learning.

Participants who received imperceptible tVNS paired with two Mandarin tones that are typically easier for English speakers to tell apart showed quick improvements in learning to distinguish these tones. By the end of the training, those participants were 13% better on average at classifying tones and reached peak performance twice as quickly as control participants who wore the tVNS device but never received stimulation.

“There’s a general feeling that people can’t learn the sound patterns of a new language in adulthood, but our work historically has shown that’s not true for everyone,” Chandrasekaran said. “In this study, we are seeing that tVNS reduces those individual differences more than any other intervention I’ve seen.”

“This approach may be leveling the playing field of natural variability in language learning ability,” added Leonard. “In general, people tend to get discouraged by how hard language learning can be, but if you could give someone 13% to 15% better results after their first session, maybe they’d be more likely to want to continue.”

The researchers now are testing whether longer training sessions with tVNS can impact participants’ ability to learn to discriminate two tones that are harder for English speakers to differentiate, which was not significantly improved in the current study.

Stimulation of the vagus nerve has been used to treat epilepsy for decades and has recently been linked to benefits for a wide range of issues ranging from depression to inflammatory disease, though exactly how these benefits are conferred remains unclear. But most of these findings have used invasive forms of stimulation involving an impulse generator implanted in the chest. By contrast, the ability to evoke significant boosts to learning using simple, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation could lead to significantly cheaper and safer clinical and commercial applications.

The researchers suspect tVNS boosts learning by broadly enhancing neurotransmitter signaling across wide swaths of the brain to temporarily boost attention to the auditory stimulus being presented and promote long-term learning, though more research is needed to verify this mechanism.

“We’re showing robust learning effects in a completely non-invasive and safe way, which potentially makes the technology scalable to a broader array of consumer and medical applications, such as rehabilitation after stroke,” Chandrasekaran said. “Our next step is to understand the underlying neural mechanism and establish the ideal set of stimulation parameters that could maximize brain plasticity. We view tVNS as a potent tool that could enhance rehabilitation in individuals with brain damage.”

Additional authors are Jacie McHaney of Pitt, and William Schuerman and Han Yi of UCSF.

The research was funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Targeted Neuroplasticity Program.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!

At what frequency is tVNS done to achieve the results gotten?