“In these uncertain times” might be the catchphrase right now. From the macro level of the pandemic, climate change, social and political unrest to the personal level of job uncertainty, illnesses within families and various levels of social isolation – any and all of these contribute to a sense of uncertainty.

But what is uncertainty? What’s going on in the brain when we feel uncertain? And how might long-term uncertainty experienced by an entire population affect community health?

“Uncertainty means ambiguity, which means that we have to expend effort in trying to predict what will happen in addition to preparing to deal with all of the different outcomes,” said Aoife O’Donovan, PhD, an associate professor of psychiatry at the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences who studies the ways psychological stress can lead to mental disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The stress of uncertainty, especially when prolonged, is among the most insidious stressors we experience as human beings, said O’Donovan.

But, when faced with these feelings, it can help to recognize that gnawing uncertainty is the amplification of a cognitive mechanism that’s essential for our survival.

The Danger of Wide-Open Spaces

What we think of as uncertainty is, at its simplest, the brain trying to choose a course of action. From an evolutionary standpoint, this means making decisions that affect survival and reproduction.

Uncertainty is a close relative of anxiety.

“Uncertainty is not knowing what is going to happen,” said Mazen Kheirbek, PhD, an associate professor in UC San Francisco’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

Combine “uncertainty” with “threat” and you get anxiety. “Anxiety is an emotional response to a perceived threat that’s not actually there in front of you,” Kheirbek said.

Anxiety is an emotional response to a perceived threat that’s not actually there in front of you.

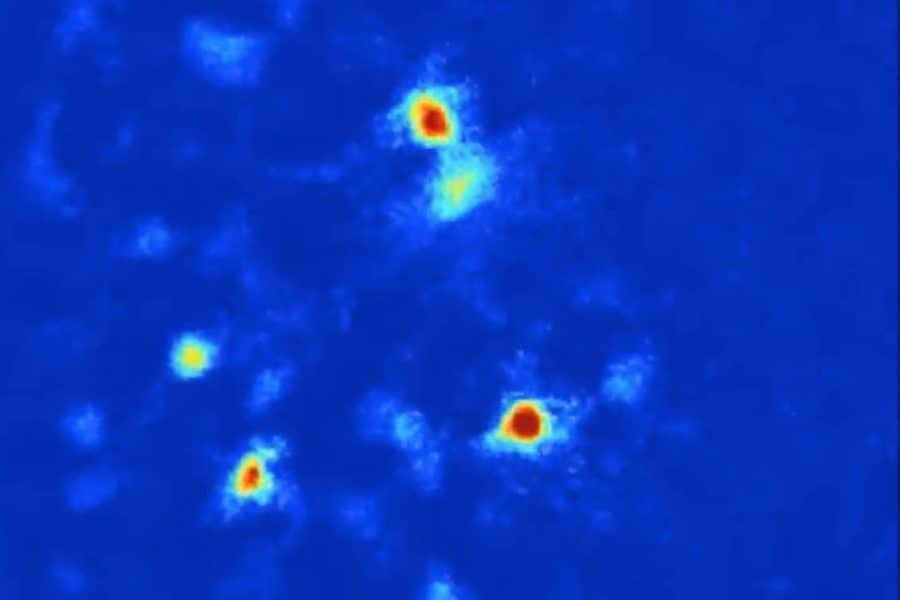

Kheirbek’s lab uses mice to understand the brain circuitry involved in emotional behavior, like anxiety. Mice prefer confined dark spaces and associate wide-open spaces with increased risk, and therefore increased anxiety. By recording brain activity when mice entered these anxiety-provoking spaces, Kheirbek’s team saw activation in certain neurons in the ventral hippocampus, a part of the brain involved in memory and emotions.

These “anxiety neurons” in turn talk to the hypothalamus, a brain region that triggers avoidance behaviors, in a pathway that seems to circumvent higher-order brain regions. The researchers showed that when they turned off those “anxiety neurons,” the mice suddenly started exploring the open space, an indication that their anxiety had abated.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!