Parkinson’s disease, which afflicts one million Americans, causes both unwanted movements, such as hand tremors, as well as difficulty in initiating movements, such as taking a step. These symptoms interfere with the ability to do many everyday activities most people take for granted.

Medicines help, but lose their power as the disease progresses.

Another, newer option is deep brain stimulation, in which small pulses of electricity are delivered to the brain using an implanted electrode. If the implantation is successful, a patient’s motor symptoms can be reduced significantly.

This technology is made possible by an ever-growing understanding of brain anatomy and the roles played by its various parts. The subthalmic nucleus (STN), for example, is part of the basic movement circuitry in the brain. In Parkinson’s patients, the STN fires in synchrony with other areas of the brain when it shouldn’t, causing problems with movement.

Pulses of electricity can disrupt this faulty firing. Cameron McIntyre, Ph.D., an expert in deep brain stimulation, says, “You’re not necessarily restoring the brain back to normal. You’re overriding pathological activity and replacing it with white noise.” McIntyre will be joining the Duke faculty in July 2021 with appointments in biomedical engineering and neurosurgery.

“When we do AI for health, the impact for society is very clear.”

Guillermo Sapiro

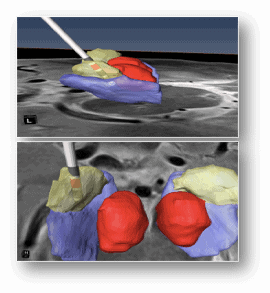

The problem? The STN is tiny, just larger than a grain of rice. “First you need to figure out where the STN is,” McIntyre says. “Each person’s brain is different — your brain and my brain and your neighbor’s brain are so different in size and shape it’s crazy. Once you find it, there are parts within that little area you want to stimulate and parts you don’t.”

Even for brain surgeons, navigating this maze is not a trivial task.

That’s where Guillermo Sapiro, Ph.D., comes in. Sapiro is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering, with appointments in computer science and mathematics. He is also a pioneering figure in artificial intelligence (AI) research. Sapiro wields his expertise in AI to solve societal problems, particularly those related to health and health care.

In the Parkinson’s project, Sapiro uses a technique called machine learning to help neurosurgeons home in on the precise area where the electrode should go. By “learning” on existing MRI images where experts identified the target location, a computer program he created can now predict the precise spot for electrode placement on any new MRI image.

The tool, which essentially builds an anatomical brain map for each individual patient, will allow more brain surgeons to be able to offer the surgery to Parkinson’s patients.

Sapiro collaborates closely on the project with a team of surgeons and scientists that includes not only McIntyre, but also Warren Grill, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering, and Dennis Turner, M.D., a neurosurgeon and professor in the departments of neurosurgery, biomedical engineering, neurobiology and orthopaedic surgery.

“We have a comprehensive system where we can go from design to surgery,” Sapiro says. “If we didn’t have such expertise in neurosurgery, we would be stuck with our idea but it would be hard to put into practice.”

Sapiro is excited to collaborate on other brain-related projects with McIntyre and the rest of the team in the future. “Duke has the chance to lead in what we are calling computational neurosurgery,” he says.

In another project, Sapiro has created a machine learning program to help identify cancerous lesions in images taken by a small, handheld device intended to be used for cervical exams in low-resource settings. The device, called a pocket colposcope, was designed by Nimmi Ramanujam, Ph.D., the Robert W. Carr, Jr., Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering. In parts of the world with limited health care equipment and providers, many women die of cervical cancer despite the fact that it’s one of the most highly treatable forms of cancer. Ramanujam and Sapiro hope the inexpensive and easy-to-use pocket colposcope will change that.

No matter the medical subspecialty, Sapiro is motivated by the idea of improving health care for all, which he refers to as the democratization of health care.

“When we are doing AI for the sake of AI, it’s not clear where the impact is,” he says. “When we do AI for health, the impact for society is very clear. It’s about ‘How do we move Duke Health expertise to everybody?’ If I can make a system that reads mammography just like the radiologists at Duke are able to do, then we can get that unique Duke Radiology expertise to everybody.”

Sapiro credits the intensely collaborative relationship between the School of Medicine and researchers in the university with making these projects possible.

“Duke is way ahead of almost any other university I can think of in terms of the connection between the university side and health side,” he says. “There is a clear understanding about the opportunity from both sides and, by the way, that’s shown by how many of the faculty at Duke have joint appointments between the School of Medicine and the university.”

One MillionAmericans affected by Parkinson’s disease

That culture of interdisciplinary collaboration is what brought McIntyre to Duke. He rattles off a list of expert investigators from the School of Medicine, the Pratt School of Engineering, and the Trinity College of Arts & Sciences. “All those people — we all complement each other in a really spectacular way,” he says. “Duke is really the only place that has all of those things on the same campus.”

Even better, McIntyre says, his collaborators are all top-notch: “We can do something far more special when each component of the problem is handled by someone who is legitimately a world expert in their area.”

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!