When Erin Hecht was earning her Ph.D. in neuroscience more than a decade ago, she watched a nature special on the Russian farm-fox experiment, one of the best-known studies on animal domestication.

The focus of that ongoing research, which began in 1958, is to try to understand the process by which wild wolves became domesticated dogs. Scientists have been selectively breeding two strains of silver fox — an animal closely related to dogs — to exhibit certain behaviors. One is bred to be tame and display dog-like behaviors with people, such as licking and tail-wagging, and the other to react with defensive aggression when faced with human contact. A third strain acts as the control and isn’t bred for any specific behaviors.

Hecht, who’s now an assistant professor in the Harvard Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, was fascinated by the experiment, which has helped scientists closely analyze the effects of domestication on genetics and behavior. But she also thought something fundamental was missing. What she didn’t know was that filling that knowledge gap could potentially force reconsideration of what was known about the connection between evolutionary changes in behavior and those in the brain.

“In that TV show, there was nothing about the brain,” Hecht said. “I thought it was kind of crazy that there’s this perfect opportunity to be studying how changes in brain anatomy are related to changes in the genome and changes in behavior, but nobody was really doing it yet.”

Hecht acted fast and sent an email to Lyudmila N. Trut, the scientist running the Siberian institute where the Russian foxes were being studied. Fast forward to today and that email was foundational for a surprising new study emerging from the fox-farm animals. Published Monday in the Journal of Neuroscience, the paper raises questions about some of the leading theories on domesticated animals’ brains.

A photo of a fox accompanied by a stylized image showing the placement of the brain.

Photo and illustration by Jennifer Johnson, Darya Shepeleva, Anna Kukekova, and Erin Hecht

By analyzing MRI scans of the foxes, Hecht and her colleagues showed that both the foxes bred to be tame and those bred to be aggressive have larger brains and more gray matter than those of the control group. These findings run contrary to other studies on chickens, sheep, cats, dogs, horses, and other animals that have shown domesticated species have smaller brains, with less gray matter, than their wild forebears.

Hecht and her team of researchers from Harvard, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Emory University, Cornell University, and the Russian Institute of Cytology and Genetics say they can’t be sure why this happens without further study. Their leading hypothesis centers on how the tame and aggressive strains have both been bred for specific behaviors at an accelerated time frame compared with many other domesticated animals. Dogs, for example, have been domesticated for at least 15,000 years.

“Both the tame and aggressive strains have been subject to intense, sustained selection on behavior, while the conventional strain undergoes no such intentional selection,” they wrote. “Thus, it is possible that fast evolution of behavior, at least initially, may generally proceed via increases in gray matter.”

As they analyzed the MRI scans, scientists noticed another surprise: similarities in the ways that the brains of the aggressive and tame foxes were changing. Both, for instance, showed enlargement in many of the same regions, including the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the cerebellum.

Results suggest that selection for opposite behavioral responses can produce similar changes in brain anatomy. It also appears that significant shifts in the structure and organization of the nervous system can evolve very quickly. In fact, it can happen within the span of less than 100 generations.

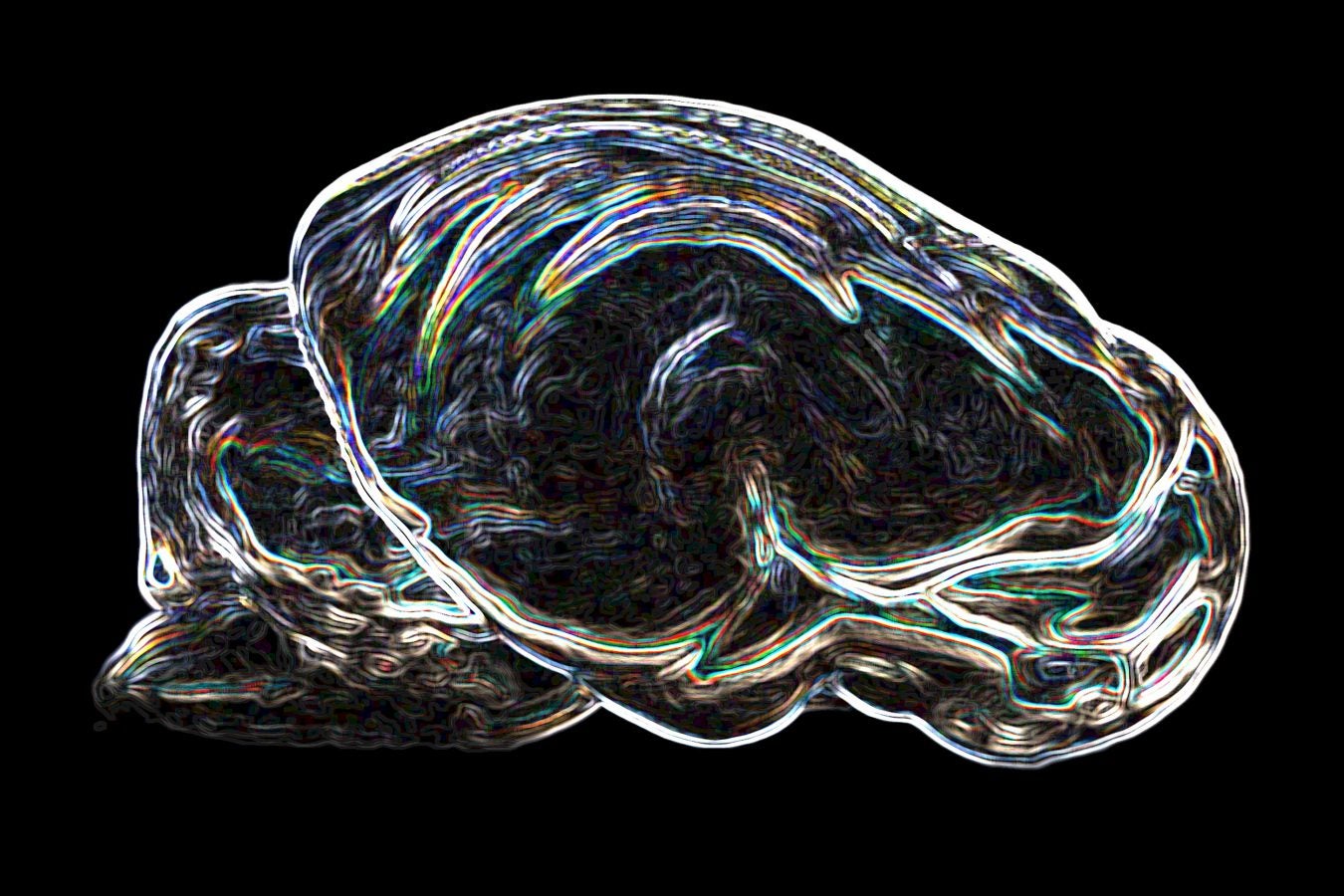

A stylized image of a fox brain.

Illustration by Jennifer Johnson, Darya Shepeleva, Anna Kukekova, and Erin Hecht

Taken together, the researchers say the study’s findings suggest existing ideas of brain changes in domestication may need revising, and that the brains of other animals, including humans, may have gone through similarly abrupt morphological shifts during times when rapid changes in environment or climate made certain behaviors more evolutionarily advantageous.

Next steps in the research include observing the foxes’ brains scans at a cellular level.

The researchers believe there’s a lot left to be learned from the Russian farm foxes and domesticated species, in general. That’s because when a species splits from its wild counterpart, its brain, body, and behavior undergo rapid changes. Studying the foxes and other domesticated animals provides a window into these complex evolutionary processes.

“It’s a more simple and straightforward way to see how evolution changes brains than we can achieve with just studying naturally occurring evolved brain changes,” Hecht said.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!